by BIEN | Dec 30, 2016 | Bios & background Info, Opinion, Testimonies

Photo taken by Stefan Pangritz at a solidarity meeting for the Swiss

referendum in January 2014 in Basel.

Toru Yamamori (Basic Income News editor)

1. Encounter to the idea

My encounter to the idea of a basic income was around 1991-2. I was involved in solidarity activism with a casual worker’s trade union, in which many of the members were homeless construction workers. Some left leaning intellectuals also came to show their solidarity from time to time, and one of them told me that what we need is the idea of ‘unconditional social income’ that was articulated in the Italian autonomist movement.

I wasn’t impressed by the idea at that time, mainly because the movement with which we were in solidarity demanded an end to unfairly unpaid or underpaid wages. For me asking ‘income’ in that context sounded like that we are getting amnesty when we want to be proved not guilty.

It took several years for me to digest why we need an unconditional basic income. Then it become a secret joy to read Bertrand Russell’s Roads to Freedom, or Philippe van Parijs’s Real Freedom for All, borrowed from a university library. Because the majority of my friends either from activism or academia didn’t like the idea, it remained a personal relief by dreaming a totally different world.

2. Joining BIEN

In 2002 I travelled to the U.K. to visit to Malcolm Torry, Philip Vince (both from Citizen’s Income Trust), and Bill Jordan (a founding member of BIEN). Malcolm and Philip showed me that the idea was being spread widely from a small alternative sphere. Bill introduced me to the working class people who demanded a basic income in 1970s, which made me remind my old friends with who I wanted to be in solidarity. (So I started to organize public events on UBI outside academia.)

In 2004 I attended the BIEN congress in Barcelona where the network changed from ‘European’ to ‘Earth’. I was fascinated by the unique atmosphere, where established, well-known academics talked with anyone in equal and friendly terms, and where many young activists brought enthusiasm. I immediately became a life member.

Then I attended almost every congress except 2006. The one in 2014 Montreal was special occasion for me, because I presented my 13 years of oral historical research on the working class feminists who demanded UBI in the 1970s Britain, which was started when Bill introduced me some of those people in 2002. Local and international feminists in the congress encouraged me with positive comments, and I felt relieved that finally I succeeded to convey their forgotten struggle to similar minded contemporary feminists.

3. And now…

I was the only participant from Asia in the 2004 congress. The number has grown and this year the congress was held in Korea, and we have five national or regional affiliates in Asia.

People in BIEN keep encouraging me to engage both activism and research on UBI, which means a lot for me. In 2012 I was elected to the Executive Committee. At that time it was out of blue, but since then I have tried to expand this unique broad-church organization, especially by writing news for the Basic Income News, and by exploring communications between Asian members.

Toru Yamamori is a professor of economics of a Doshisha University in Kyoto, Japan.

At the end of 2016, the year in which BIEN celebrated the 30th anniversary of its birth, all Life Members were invited to reflect on their own personal journeys with the organization. See other contributions to the feature edition here.

by Kate McFarland | Dec 29, 2016 | News

Timotheus Höttges, CEO of the multibillion dollar telecommunications company Deutsche Telekom AG, has previously expressed support of unconditional basic income. In December 2016, he again addressed the subject in an interview in the German business newspaper Handelsblatt.

In a recent interview with Handelsblatt, Telekom CEO Timotheus Höttges talks about the changing nature of work, especially potential job loss due to digitization — to which, he admits, his own company is not immune — and the demand for more specialized skills. In response to a question about why he supports an unconditional basic income (“bedingungsloses Grundeinkommen”), he notes that jobs are becoming more project-based, with permanent full-time employment becoming less of a norm.

Timotheus Höttges

Between digitization and project-based work structures, we should expect that workers will need more time to retrain as well as more periods of unemployment or part-time employment — and, according to Höttges, Germany’s current welfare system is ill-equipped to support such workers. Thus, he believes that the government should replace its complex system of subsidies with an unconditional basic income [1].

Höttges adds that an unconditional basic income would promote more dignity (“Würde”) than Germany’s current welfare system — which puts the would-be recipient in the position of a supplicant, having to ask for aid — and that it could promote entrepreneurship.

Although he admits that some might take advantage of the basic income without contributing to society, Höttges denies that a basic income would create a “society of loafers” (“Gesellschaft von Faulenzern”), since it is through work that people find meaning and identity.

Höttges also points out that a basic income would encourage respect for those who choose to do work that is traditionally unpaid, giving the example of care for ailing parents. (It’s worth noting in this connection that, earlier in the interview, Höttges argues that revenue is no longer an adequate measure of productivity, given the extent to which information can now be created and distributed freely, as in Wikipedia.)

When asked about funding for an unconditional basic income, Höttges stresses that the policy needs to be seen as part of a broader package of a reforms, including tax reform. He maintains that corporate profits must be taxed and redistributed as a matter of justice, fairness, and solidarity (“Gerechtigkeit, Fairness, Solidarität”).

The interview also mentions top-ranked German CEOs who are sympathetic to basic income, including Götz Werner of dm-drogerie markt — with whom Höttges has discussed the idea — and Siemens CEO Joe Kaeser, who called for “a kind of basic income” during the Süddeutsche Zeitung Economic Summit in November (although he subsequently indicated in a Tweet that he did not believe the basic income needed to be unconditional).

If you read German, you can read the entire interview here:

Ina Karabasz, “Telekom Timotheus Höttges CEO: ‘Wir sind zu satt’,” Handelsblatt, December 20, 2016.

[1] In the original German: “Also wird es Phasen geben, in denen der Mensch keine Arbeit hat, umschult oder nur in Teilzeit für ein Unternehmen arbeitet. Diese Phasen wird der Sozialstaat überbrücken müssen. Warum soll man dessen komplexe Förderungssystematik nicht mit einem bedingungslosen Grundeinkommen ersetzen?”

Timotheus Höttges photos: CC BY-SA 4.0 Sebaso

by Guest Contributor | Dec 24, 2016 | Opinion

“Quatinga Velho, the lifetime Basic Income”

The nonprofit organization ReCivitas distributed a basic income to residents of the Brazilian village Quatinga Velho from 2008 to 2014. In January 2016, ReCivitas launched a new initiative, Basic Income Startup, which aspires to resume the Quatinga Velho basic income payments and make them lifelong.

A new initiative, the Basic Income Projects Network, aims to bring together other nongovernmental organizations that wish to start their own privately-funded basic income pilots.

Marcus Brancaglione, president of ReCivitas, writes this update:

The ReCivitas Institute is an NGO founded in 2006 that works to apply factual guarantees to human rights in independent public policies.

Since 2008, we have developed and sustained the Unconditional Basic Income pilot project in Quatinga Velho, Brazil, which is an internationally recognized project in Basic Income studies and research.

Since 2008, we have developed and sustained the Unconditional Basic Income pilot project in Quatinga Velho, Brazil, which is an internationally recognized project in Basic Income studies and research.

As of January 16th, 2016, Basic Income payments are now permanent, and no longer just a part of an experiment. For 14 people the Unconditional Basic Income has started to be for a lifetime. Now, with our enhanced peer-to-peer model, they also contribute, according to their ability to do so, to these payments.

The project is now called BASIC INCOME STARTUP, because for every 1,000 Euros donated, for no additional cost, a new person that lives anywhere that 40 Reais can make a difference (that is, a person that really needs that money) will start to receive the lifetime basic income.

And it bears emphasizing: for every 1,000 Euros that are donated, RECIVITAS will remove one person from the most abject conditions of primitive deprivation — the kinds of conditions that every Basic Income activist should never forget actually exists.

And it bears emphasizing: for every 1,000 Euros that are donated, RECIVITAS will remove one person from the most abject conditions of primitive deprivation — the kinds of conditions that every Basic Income activist should never forget actually exists.

This project was designed during our last trip to Europe in 2015, while we observed the inequality between refugees and European citizens.

In Brazil, the Brazilian Network for Basic Income is being formed by local communities and independent institutions. The aim is to expand and replicate the model in the ghetto, forgotten places of the world, because poverty has a face and an address, therefore programs that fight poverty do not need focusing techniques or conditionalities, because the people who are in dire need of help already live in segregation.

ReCivitas would like to use this rare opportunity to invite other projects and local communities that are paying, or wish to pay, a basic income, to join us and form the Basic Income Projects Network.

Through partnerships with local organizations, the Quatinga Velho model can be replicated in any community around the world, including ones with the same difficulties: with small amounts of their own capital, no governmental support or support by private corporations, and some amount of international solidarity and support.

Through partnerships with local organizations, the Quatinga Velho model can be replicated in any community around the world, including ones with the same difficulties: with small amounts of their own capital, no governmental support or support by private corporations, and some amount of international solidarity and support.

We have decided to propose this partnership, especially after the World Social Forum, for two reasons. First, because we have finally realized how much we have accumulated in shareable knowledge in these ten years— knowledge that must be shared with those who really want to accomplish things. Second, because we want to help in the construction of these new projects, especially the ones that are more open to those who really need them.

For more information about the network, including the terms of the partnership for participating groups, please see the “Basic Income Project Network” page on the ReCivitas website.

Marcus Brancaglione, President of ReCivitas

by Guest Contributor | Dec 6, 2016 | Opinion

Written by: Pierre Madden

On November 12 and 13 I attended a congress of the Liberal Party of Quebec, which is currently in power in the province.

The Minister of Employment and Social Solidarity, François Blais, confirmed that a joint working group, with his colleague in Finance, will issue a preliminary report on Basic Income in the Spring. Our neighbouring province of Ontario (which, together with Quebec accounts for 62 percent of the population of Canada) was just released a working paper on a pilot project to begin in April 2017. Quebec does not seem to be leaning towards a pilot project.

In his talk, Minister Blais placed much emphasis on the principles underlying the development of the government’s project:

- The development of human capital (though education, for example)

- The obligation of protection from certain risks (with unemployment insurance and health insurance, for example)

- Income redistribution

The minister’s speech was highly focused on incentives to work or study (especially for the illiterate or those without a high school diploma).

The principle of unconditionality, a fundamental aspect of Basic Income, will likely not be a feature of the government’s plan.

On the second day of the congress it was the minister’s turn to ask me if he had answered my question. I described my own situation as a case in point. I am 62, three years away from my public pension which here in Canada is sufficient to raise most people out of poverty (works for me!). Why would the government be interested in the development of my human capital? The minister replies: “In a case like yours, we would have to go back in time to see what choices you made.” I have several university diplomas, which doesn’t help his argument. I am still either underemployed or unemployable.

The minister could only answer: “I would have to know more about your individual case.”

And that is what the government does and will continue to do for all those considered “fit for work.” Petty bureaucratic inconveniences for those “unfit for work” will be removed and their inadequate benefits will be improved by dipping into the funds previously used for the “fit” as they return to the workforce. The government sees no difficulty in a law it passed just last week (Bill 70: An Act to allow a better match between training and jobs and to facilitate labour market entry). The government highlights the positive measures it imposes to help participants join the job market. Those who prefer a non-paternalistic approach (“Give me the money and let me make my own decisions”) are penalized.

The irony is that before he entered politics Minister Blais actually wrote a book in support of Basic Income for all. He confirmed to me that he still believes what he wrote 15 years ago.

In Canada, both the federal and the provincial governments partially reimburse sales tax. Here in Quebec, the Solidarity Tax Credit refunds part of the estimated sales tax paid by consumers. The higher your income, the lower the monthly payout, so it works like a negative income tax. The minister was asked about this as a stepping stone towards Basic Income. He simply said it would be “a more radical approach.” Of course, tax credits don’t impact on “human capital.”

You can be sure I will be rereading François Blais’ book when his work-group’s report comes out next year.

About the author: Pierre Madden is a zealous dilettante based in Montreal. He has been a linguist, a chemist, a purchasing coordinator, a production planner and a lawyer. His interest in Basic Income, he says, is personal. He sure could use it now!

by Guest Contributor | Nov 21, 2016 | Opinion

Original post can be found at TRANSIT

Written by Bonno Pel & Julia Backhaus

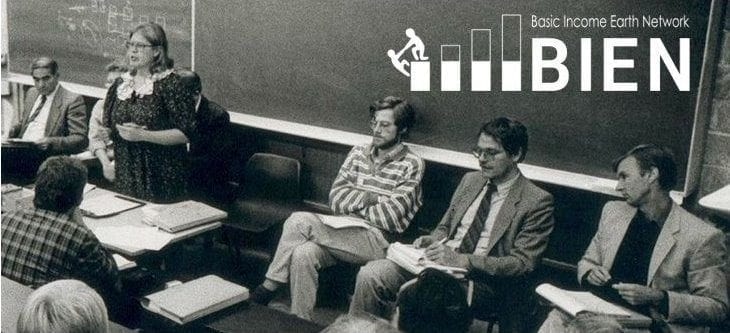

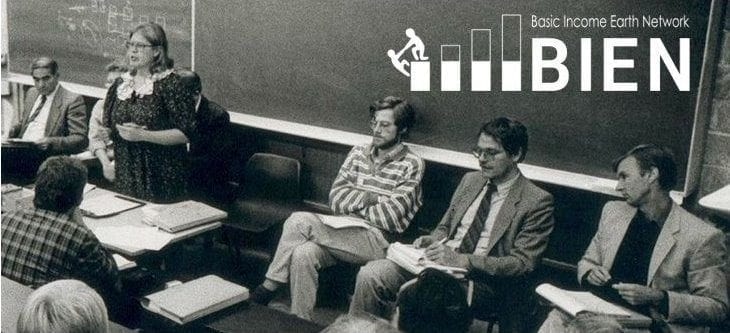

On Saturday October 1st 2016, the Basic Income Earth Network celebrated its 30th anniversary at the Catholic University of Louvain in Louvain-la-Neuve (Belgium). The picture shows the founding meeting in 1986, but is also quite applicable to BIEN 30 years later. The conference was held at the same location and many of the founders and their fellow militants met in good atmosphere to commemorate the early beginnings of the network. Together with other scholars and generally interested people, they discussed current developments in science and policy and ‘the way forward’ for the basic income movement.

picture source

An unconditional income for all

First, the picture is telling for the ways in which BIEN pursues transformative social innovation, namely through the development, discussion and dissemination of persuasive “new framings” and “new knowings”. The seminar room in the picture gathers several individuals who by now have become eminent scholars in economy, social philosophy or sociology. Over the course of three decades and together with activists, politicians and citizens, BIEN members have developed a whole complex of arguments, evidence and framings around the basic income. The idea itself is simple: An unconditional, individual income entitlement, more or less sufficient for fulfilling basic needs, promises real freedom for all.

It offers individual empowerment in the form of income security and the material conditions for a self-determined existence in society, but it is also in many aspects about changing social relations: between men and women (as the conventional breadwinner model is challenged by individual income entitlements), between employed and unemployed (as stigmatization lessens when entitlement is universal rather than for the ‘unproductive’ only), and between employee and employer (the latter’s possibilities to exploit the former are decreased by the basic income security). In current institutional-ideological constellations, the idea of a basic income is bizarre and outrageous for rewarding jobless ‘free-riders’. Apparently relinquishing hard-earned social security arrangements, BIEN members met (and continue to meet) with tough press, sidelining them as ‘irresponsible freaks’. Yet the power of BIEN members’ socially innovative agency resides in showing that it is actually many common ideas about work and income that are outdated, and harmful even.

Claus Offe (credit: Enno Schmidt)

Impressive examples of outdated conceptions were provided by prof. Claus Offe, who argued that we do not earn our income, as commonly believed. Wage flows from labour that forms part of ever-extending production chains of individuals and machines. The availability of jobs fluctuates cyclically, and independently from individuals’ employability efforts. Moreover, the current productivity in highly industrialized countries is possible because ‘we stand on the shoulders of giants’. It is largely inherited from previous generations. So it is rather the current insistence on employability, on meritocracy and on ‘earning one’s income’ that is out of tune with economic reality. Production has become post-individual, and this requires a matching social security system. Harmful effects of a capitalist system that ignores its obviously collective character through individualist ideology include blaming the losers and accepting precarious conditions for some. Economist Gérard Roland outlined how the basic income provides a better trade-off between labor market flexibility and precariousness than current social security arrangements. Sociologist Erik O. Wright views the basic income as a “subversive, anti-capitalist project”. He expanded how the concept allows moving on from merely taming to escaping the globalized, capitalist system. For him, the basic income can provide the basis for numerous social innovations that also the TRANSIT project considers, such as social and solidarity economy initiatives or co-operatives.

BIEN thriving on internal differences: many streams forming a river

Second, based on the variance of people’s clothing, the picture above also visualizes how BIEN has developed as an association of very different individuals. At the conference various founding members recalled the routes they had traveled towards the transformative concept. They arrived at the idea on the search for liberalist re-interpretations of Marx, through feminist commitments, when rethinking meritocracy, as a response to the structural unemployment of the time, or as a logical conclusion of a transforming and ‘robotizing’ economy. The forthcoming case study report on BIEN by yours truly spells out in more detail how these different little streams came to ‘form a river’, as expressed by a founding member. The internal differences between the generally principled and intellectually sharp BIEN members led to fierce debates, it was recalled. According to a longstanding motor, evangelizer and lobbyist for the basic income, BIEN has only survived as a network for members’ capacity to ‘step back a bit’ from their ideological disputes at times, and to recognize what united them. BIEN even thrived on its internal divisions. It functioned as a discussion platform, and helped to institutionalize basic income as a research field. Since 2006, there is even an academic journal on this example of transformative social innovation: Basic Income Studies.

Evolving communication: spreading the word

Philippe Van Parijs (credit: Enno Schmidt)

Third, the black and white photo immediately suggests how different the world was three decades ago. At the time of founding, network members and conference participants from various countries had to be recruited through letters. Initially, the newsletter was printed out, put in envelopes and stamped, for which members gratefully sent envelopes with pesetas, Deutschmarks and all the other European currencies, subsequently converted at the bank by standard bearer professor Philippe Van Parijs and his colleagues. Today’s e-mail, website and Youtube recordings obviously make a crucial difference when it comes to facilitating discussion and spreading the word fast and wide – especially for this social innovation that primarily travels in the form of ideas. The presentations on the history of basic income underlined the significance of the communication infrastructure. The history of basic income can be conceived of as a long line of individuals working in relative isolation, often not knowing of others developing similar thoughts and blueprints. The evolution of BIEN very instructively shows the importance of evolving communication channels and knowledge production for transformative social innovation – critical, weakly-positioned, under-resourced individuals no longer need to re-invent the wheel in isolation.

BIEN, a research community? Ways forward

A fourth, telling element the picture above is the confinement of the seminar room. There have been discussions about BIEN’s existence as a researchers’ community, with the expert-layman divides it entails (during this meeting of experts, yours truly fell somewhat in the latter category). There are in fact also other networks of basic income proponents that have rather developed as citizen’s initiatives and activist networks. BIEN, as a network that can boast such a high degree of conceptual deepening and specialization, is illustrative for the ways in which it remains confined in its own room. It is significant in this respect that the current co-chair brought forward two lines along which the network should reach out more. First, BIEN should be more receptive towards and engaging with the various attempts to re-invent current welfare state arrangements. While this may imply using a more practical language and taking off the sharp edges it may yield real contributions to social security. Often these change processes (regarding less stringent workfare policies, for example) are not undertaken under spectacular headings and transformative banners, but they involve application of some basic income tenets such as unconditional income entitlements. A second line for outreaching confirms the importance of comparative research into transformative social innovation like TRANSIT: The co-chair highlighted that BIEN will explore and develop its linkages with other initiatives, such as Timebanks and alternative agriculture movements more actively.

Basic income: a ‘powerful idea, whose time has come?’

Fifth and finally, the seminar room setting depicted in the photo raises attention to the knowledge production that BIEN has been and is involved in. The socially innovative agency of its members can be characterized as ‘speaking truth to power’. Basic income activism has taken the shape of critiques, pamphlets and counterfactual storylines (Thomas More’s ‘Utopia’ being a 500 year-old example), but also featured modeling exercises, forecasts, and economic evidence to support the case. BIEN members’ key resource is their expertise. Moreover, considering the strong arguments and evidence gathered in favor of the basic income over the past decades, there are reasons to be confident in basic income ending up as the ‘powerful idea, whose time has come’. As described in Pel & Backhaus (2016) and currently considered further, it is remarkable how much BIEN seems to have developed in line with the trend of evidence-based policy. The commitment to hard evidence gives rise to an important internal discussion on the recent developments towards basic income-inspired experimentation (such as in Finland and in the Netherlands). The common stance of BIEN members is that these experiments fall short of providing any reliable evidence for their limited duration and scope, and for the system-confirming evaluative frameworks that tend to accompany them. However, there is also a somewhat growing attentiveness to the broader societal significance of experiments and pilots in terms of legitimization, awareness-raising and media exposure. It is therefore instructive for the development of TSI theory to study the basic income case for the new ways in which ‘socially innovative knowings’ are co-produced and disseminated.

About the authors:

Bono Pel (Université libre de Bruxelles; bonno.pel@ulb.ac.be) and Julia Backhaus (Maastricht University; j.backhaus@maastrichtuniverstiy.nl) are working on TRANSIT (TRANsformative Social Innovation Theory), an international research project that aims to develop a theory of transformative social innovation that is useful to both research and practice. They are studying the basic income as a case of social innovation, focusing on national and international basic income networks and initiatives.

Since 2008, we have developed and sustained the Unconditional Basic Income pilot project in Quatinga Velho, Brazil, which is an internationally recognized project in Basic Income studies and research.

Since 2008, we have developed and sustained the Unconditional Basic Income pilot project in Quatinga Velho, Brazil, which is an internationally recognized project in Basic Income studies and research. And it bears emphasizing: for every 1,000 Euros that are donated, RECIVITAS will remove one person from the most abject conditions of primitive deprivation — the kinds of conditions that every Basic Income activist should never forget actually exists.

And it bears emphasizing: for every 1,000 Euros that are donated, RECIVITAS will remove one person from the most abject conditions of primitive deprivation — the kinds of conditions that every Basic Income activist should never forget actually exists. Through partnerships with local organizations, the Quatinga Velho model can be replicated in any community around the world, including ones with the same difficulties: with small amounts of their own capital, no governmental support or support by private corporations, and some amount of international solidarity and support.

Through partnerships with local organizations, the Quatinga Velho model can be replicated in any community around the world, including ones with the same difficulties: with small amounts of their own capital, no governmental support or support by private corporations, and some amount of international solidarity and support.