by Andre Coelho | Feb 12, 2018 | News, Research

Ville-Veikko Pulkka

Although an experiment on basic income is being performed in Finland at the moment (being expected to end by January 2019), this does not say much about what Finns think about it, or about basic income in general. According to recent research developed by Ville-Veikko Pulkka, a doctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki, not only does survey methodology deeply affect people’s responses, but current beliefs and views of society by Finnish citizens are also such that “there is no need for a paradigm shift”.

Ville-Veikko and his colleague Professor Heikki Hiilamo ran another survey in late 2017, arguing that other surveys on basic income in Finland such as Center party’s think tank e2 in 2015, Finnish Social Insurance Institution (Kela) in 2015, and Finnish Business and Policy Forum EVA in 2017 skewed results due to different ways of defining and framing basic income, with support ranging from 39 up to 79%. These researchers view their survey as “a more realistic view on basic income’s support in Finland”, having it based on the Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN) definition. They also explicitly referred the basic income net level of 560 €/month, which is around as much as many basic social benefits in Finland.

Ville-Veikko and Professor Hiilamo have found that the partial basic income of 560 €/month currently being tested in Finland is actually the most supported one among several basic income options (partial(1) with more or less than 560 €/month, full(1) with 1000 or 1500 €/month), with 51% of respondents saying it is a “good idea” (20% being undecided and 21% firmly considering it a bad idea). Significantly, of the surveyed income schemes, the most supported one was “participation income” (78% of supporters) which is not a basic income by definition.

This survey also showed that the younger the respondents (around 1000 in total), the more support the basic income proposal (the one cited above) receives – 72% under 24 years of age, down to 42% for people over 65. Occupation also seems to have a strong influence, with students showing 69% of support for basic income and entrepreneurs only 38%. For relatively obvious reasons, the unemployed and part-time employed were also more in support of the idea (68 and 61% respectively).

The new survey by Ville-Veikko and Professor Hiilamo comes at a time when it becomes clear that the Finnish government’s path is not to break from “the activation policies implemented since the 1990s”. This has been shown through the recent implementation of a tighter work activation model, aimed at the unemployed, which brings more conditionality and sanctions into the system. This is, apparently, contrary to the basic income spirit of unconditionality and, on top of that, the government is already considering tightening up unemployment benefits even further.

From the referred survey and recent Finnish government moves toward activation policies, it seems clear that running an experiment on basic income does not equate to leading the way towards the implementation of this policy. According to Ville-Veikko, basic income in Finland is likely to receive more support if only unemployment and work precarity rises significantly in the near future, which is uncertain even given the latest studies on the subject. It also becomes clear that the public remains polarized regarding social policies for the future: on the one hand there is moderate support for basic income, and on the other hand there is clear support for activation measures such as the “participation income”.

Notes:

1 – here, “partial” refers to receiving the stipend and maintaining eligibility for housing allowance and earnings-related benefits, and “full” refers to losing eligibility to those same benefits.

More information at:

Kate McFarland, “FINLAND: First Results from Pilot Study? Not Exactly”, Basic Income News, May 10th 2017

“New model to activate unemployed comes into effect amid rising criticism”, YLE, 26th December 2017

“Finnish government plan for jobless: Apply for work weekly – or lose benefits”, YLE, 10th January 2018

Micah Kaats, “International: McKinsey report identifies basic income as a potential response to automation”, Basic Income News, 16th January 2018

by Malcolm Torry | Dec 28, 2017 | Research

Satelite picture over Europe. Credit to: TechCrunch.

A new working paper from the Institute for Social and Economic Research at the University of Essex reports on research using the EUROMOD microsimulation programme to simulate the labour market effects of several different tax and benefits reforms in countries in different parts of Europe.

The reform options tested are as follows:

- An unconditional Basic Income – correctly defined

- A general Negative Income Tax – that makes a payment if earnings fall below a threshold (the payment being proportional to the amount that wages fall below the threshold), and deducts tax above the threshold

- What the researchers call a ‘conditional basic income’ – which is a means-tested benefit that is withdrawn at a rate of 100% as earnings rise, thus constituting a guaranteed minimum income

- In-work benefits – means-tested in-work benefits without a relationship with the income tax threshold.

All of the reforms assume a flat income tax.

The research finds that the General Negative Income Tax usually promises the most efficient employment market: although in the context of the UK there is almost nothing to choose between a General Negative Income Tax and an Unconditional Basic Income. The research did not take into account the administrative complexities of a Negative Income Tax. If it had been possible to simulate the effects of administrative complexities on labour market decisions then they might have found that in the UK an Unconditional Basic Income would have turned out to be the most efficient option.

The working paper is entitled The case for NIT+FT in Europe: An empirical optimal taxation exercise, and is by Nizamul Islama and Ugo Colombinob.

Click here to read the working paper; or here to download the paper as a pdf.

Abstract

We present an exercise in empirical optimal taxation for European countries from three areas: Southern, Central and Northern Europe. For each country, we estimate a microeconometric model of labour supply for both couples and singles. A procedure that simulates the households’ choices under given tax-transfer rules is then embedded in a constrained optimization program in order to identify optimal rules under the public budget constraint. The optimality criterion is the class of Kolm’s social welfare function. The tax-transfer rules considered as candidates are members of a class that includes as special cases various versions of the Negative Income Tax: Conditional Basic Income, Unconditional Basic Income, In-Work Benefits and General Negative Income Tax, combined with a Flat Tax above the exemption level. The analysis shows that the General Negative Income Tax strictly dominates the other rules, including the current ones. In most cases the Unconditional Basic Income policy is better than the Conditional Basic Income policy. Conditional Basic Income policy may lead to a significant reduction in labour supply and poverty-trap effects. In-Work-Benefit policy in most cases is strictly dominated by the General Negative Income Tax and Unconditional Basic Income.

by Micah Kaats | Dec 24, 2017 | News, Research

In the three years since its initial publication, Rutger Bregman’s Utopia for Realists has helped spur a global conversation on universal basic income (UBI). The book has become an international bestseller, garnering praise from intellectual heavyweights and propelling its author to the TED stage this past April. However, Stephen Davies, education director at the Institute for Economic Affairs (IEA), remains skeptical of many of the young Dutch journalist’s ideas. He makes his case in the most recent edition of the Journal of Economic Affairs.

“Rutger Bregman’s book is both interesting and irritating,” declares Davies in the opening line of his review. To clarify, he quickly notes that it is interesting “not so much because of its particular content…but because it gives us an insight into what may turn out to be a development of both intellectual and political importance” (p. 442). Such an off hand rejection of a book advocating basic income from the education director of a think tank advocating free market capitalism may be unsurprising to some, but Davies’ response is actually not as inevitable as it may seem. Historically, UBI has found supporters on both sides of the political divide.

Davies distinguishes between two types of arguments Bregman makes for basic income. The first considers UBI to be a pragmatic solution to the shortcomings of the current social welfare system. The second considers it to be a necessary means of radically transforming the existing social order. While Davies may be more sympathetic to the second line of reasoning, he spends most of his time critiquing the first.

Steven Davies. Credit to: The London School of Economics and Political Science

In Utopia, Bregman draws on a wealth of research to highlight deficiencies in the means-tested benefit programs that constitute the welfare states of most developed societies. He notes that many of these programs create negative incentives, keeping beneficiaries locked in a poverty trap. Even worse, financial instability can result in a scarcity mindset, making it even harder for poor people to make responsible financial decisions. According to Bregman, unconditional cash transfer programs (UCTs) have proven to be the most successful remedy to this vicious cycle of poverty and dependence. In support of this view, Bregman offers additional in-depth analyses of related programs, including Richard Nixon’s Family Assistance Plan, negative income taxes, and the Speenhamland system.

Davies acknowledges the implications of this body of research. He writes, “Much of the evidence presented by Bregman is indeed very striking and should encourage us simply to trust people more and have greater confidence in their judgment and their knowledge” (p. 447). However, he is far more hesitant to interpret these results as evidence for universal basic income.

Davies notes that many of the policies Bregman touches on are in fact means-tested in one way or another, and may therefore be more analogous to standard welfare programs than basic income. Additionally, Davies argues that many of the UCT programs discussed in Utopia for Realists have not been around long enough to show lasting impacts, and he calls for more research to determine the specific amounts at which UCTs can begin to induce behavioral change. Yet, even more worrisome for Davies is the “bold assumption that there is no meaningful distinction between single lump-sum payments and continuing income stream” (p. 448). He notes that while individual cash transfers may bring sudden and liberating benefits, similar effects of ongoing basic income payments may become muted over time.

According to Davies, all of this “reveals confusion over what a UBI is thought of as being – is it a way of establishing a floor or minimum that is guaranteed to all or is it a redistributive mechanism designed to narrow income differentials?” (p. 449). This confusion motivates Davies’ second critique of Bregman’s argument for universal basic income as a response to the widening global wealth gap. While basic income programs may go a long way in ensuring no one lives in a state of absolute poverty, Davies writes that “it is not clear how a UBI by itself will do anything to reduce relative poverty or inequality” (p. 449). In fact, he notes it may even make the problem of inequality worse if UBI programs seek to replace other means-tested benefits.

However, while Davies takes issue with many of Bregman’s pragmatic arguments, he seems much more sympathetic to the idealistic aspects of his account. As automation increases and “bullshit jobs” proliferate, Davies grants Bregman his assumption that UBI could become a useful tool to decouple meaningful activity from paid work. He writes, “This is clearly the vision that truly inspires Bregman, the utopia of his book’s title, and he would have done better to stick to this rather than muddy the waters by conflating it with more limited and pragmatic discussions of a guaranteed income in a society where wage labor is still widespread and predominant” (p. 456).

While he may be unmoved by Utopia for Realists, Davies clearly recognizes the significance of the political and intellectual movements it represents. The book’s international success seems to reflect a growing anxiety about stagnation of big ideas in the face of an increasingly unsatisfying status quo. Davies concludes, “What we are starting to see is an attempt to work out what a non-capitalist or, more accurately, a post-capitalist political economy would look like” (p. 457).

Davies review appears in the most recent edition of the Journal for Economic Affairs.

by Micah Kaats | Dec 22, 2017 | News, Research

Recently, there has been a great deal of attention paid to the changing nature of work. From rising automation to the ever-expanding gig economy, the effects of shifting labor landscapes are being felt by governments, businesses, and workers around the world. A new report from Deloitte, a global consulting firm, in partnership with the Human Resources Professionals Association, wades into this discussion with an analysis of the Canadian workforce. In addition, the report offers an array of potential public policy responses to address disruptive trends in the labor market including a shorter workweek, flexible education pathways, and a basic income.

In the report, authors Stephen Harrington, Jeff Moir, and J. Scott Allinson provide analysis based on interviews with 50 leading experts, as well as a review of the relevant literature. The authors argue that Canada is on the verge of an “Intelligence Revolution” that will be shaped by three dominant trends: machine learning, increasing computing power, and automation. These “waves of disruptive change” are already being felt in the Canadian economy, and their effects will become increasingly significant over the next decade.

Specifically, the report identifies two overarching themes that have already begun to impact labor markets. First, as work becomes more decentralized, workers are increasingly finding themselves in temporary or contingent jobs. These “contingent workers” bring their skills to specific projects or tasks, moving on when the task is completed, and work for multiple companies simultaneously. These arrangements form the basis of the gig economy. Second, the researchers argue that automation is opening up new opportunities for collaborative work between machines and humans. While automation can cause job displacement in the short term, the researchers contend that new job opportunities will continue to arise as productivity increases.

However, the report also notes that individuals and institutions seem ill-prepared to adapt to the rapidly increasing pace of change. In Canada, the number of contingent workers has grown from 4.8 million in 1997 to 6.1 million in 2015. Today, approximately 1/3 of Canadian jobs are for contingent workers. However, temporary positions still pay 30% less on average than permanent positions, and private sector pension plans only cover 24% of the Canadian workforce. At the same time, while 41% of organizations have “fully implemented or made significant progress in adopting cognitive and AI technologies”, only 17% of business leaders report feeling ready to manage a workforce of robots, AI, or humans working side-by-side (p. 17).

In response, the report’s research team offers several suggestions. Eight job archetypes of the future are presented, and individuals are advised to develop “future-proof” human-centered skills in judgment, leadership, decision making, social awareness, systems thinking, and creativity. The report also recommends integrated partnerships between businesses and educational institutions to enable workers to meet the needs of a changing labor market.

However, the researchers also note that efforts by individuals and businesses alone will not be sufficient for Canada to “emerge as a winner in the Intelligence Revolution.” To this end, policy reforms must be adopted to reflect both the challenges and opportunities of a 21st century economy. Among these recommendations are a shorter workweek, increased consumption taxes, decreased income taxes, unemployment insurance, and a renewed commitment to immigration. Additionally, basic income is offered as a means to address rising automation. The researchers suggest that basic income may ease the strains of job displacement, provide support for individuals engaged in volunteer or social enterprises, and encourage entrepreneurial risk-taking.

You can read the report in full here.

by Faun Rice | Dec 21, 2017 | Research

“Wise Cities & the Universal Basic Income: Facing the Challenges of Inequality, the 4th Industrial Revolution and the New Socioeconomic Paradigm” by Josep M. Coll, was published by the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB) in November 2017. CIDOB is an independent think tank in Barcelona; its primary focus is the research and analysis of international issues.

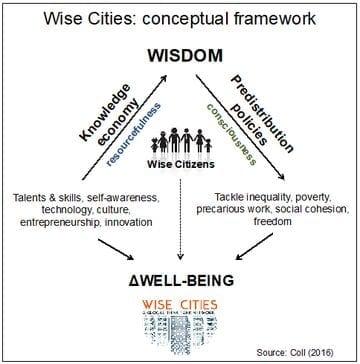

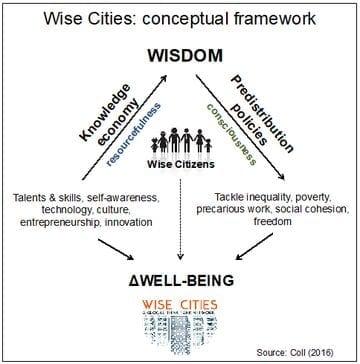

The Wise Cities Model

CIDOB has published other works about a concept it calls “Wise Cities,” a term intended to holistically encompass words like “green city” or “smart city” in popular usage. Wise Cities, as defined by CIDOB and others in the Wise Cities think tank network, are characterized by a joint focus on research and people, using new technologies to improve lives, and creating useful and trusting partnerships between citizens, government, academia, and the private sector.

The 2017 report by Coll opens with a discussion of the future of global economies; it highlights mechanization of labour, potential increases in unemployment, and financial inequality. It next points to cities as centres of both population and economic innovation and experimentation. A Wise City, the paper states, will be a hub of innovation that uses economic predistribution—where assets are equally distributed prior to government taxation and redistribution—to maximize quality of life for its citizens.

Predistribution in Europe: Pilot Projects

Universal Basic Income (UBI) is one example of a predistribution policy. After touching on UBI’s history and current popularity, Coll summarizes European projects in Finland, Utrecht, and Barcelona in order to highlight city-based predistribution experiments. Coll adds that while basic income is defined as unconditional cash payments, none of these pilots fit that definition: they all target participants who are currently, or were at some time, unemployed or low-income.

Finland’s project began in January 2017, and reduces the bureaucracy involved in social security services. It delivers an unconditional (in the sense of non-means-tested and non-work-tested after the program begins) income of 560 €/month for 2,000 randomly selected unemployed persons for two years. Eventual analysis will consist of a comparison with a larger control group of 175,000 people, and the pilot is a public initiative.

The city of Utrecht and Utrecht University designed an experiment which would also last two years, and would provide basic income of 980 €/month to participants already receiving social assistance. The evaluation would assess any change in job seeking, social activity, health and wellness, and an estimate of how much such a program would cost to implement in full. The author comments that the program was suspended by the Netherlands Ministry of Social Affairs, and the pilot is currently under negotiation.

Barcelona has begun an experiment with 1,000 adult participants in a particularly poor region of the city, who must have been social services recipients in the past. “B-Mincome” offers a graduated 400-500 €/month income depending on the household. After two years, the pilot will be assessed by examining labour market reintegration, including self-employment and education, as well as food security, health, wellbeing, social networks, and community participation. Because the income is household-based, and not paid equally to each individual, it is not a Basic Income, but the results could still provide useful evidence for the possible effects of a future Basic Income.

The Implications

Coll identifies several key takeaways from a comparison of these projects. None of the experiments assess the potential behavioural change in rich or middle class basic income recipients. In addition, multi-level governance may cause problems for basic income pilots, but these issues may be mitigated as more evidence assessing the effectiveness of UBI builds from city-driven programs. Coll also acknowledges that all of the experiments listed in his paper are from affluent regions.

In conclusion, the author argues that UBI is a necessary step to alleviate economic inequality. While cities are experimenting with the best ways to implement UBI, they are often not real UBI trials (as they are not universal), and they do not always take an individual-based approach; however, they are nevertheless useful components of the Wise City model.

More information at:

Josep M. Coll, “Why Wise Cities? Conceptual Framework,” Colección Monografı́as CIDOB, October 2016

Josep M. Coll, “Wise Cities & the Universal Basic Income: Facing the Challenges of Inequality, the 4th Industrial Revolution and the New Socioeconomic Paradigm,” Notes internacionals CIDOB no. 183, November 2017

by Andre Coelho | Dec 11, 2017 | News, Research

Picture credit to: European Parliament

On the 23rd November, Social Europe published an article by Bo Rothstein entitled ‘UBI: A bad idea for the welfare state‘:

First, such a reform would be unsustainably expensive and would thereby jeopardize the state’s ability to maintain quality in public services such as healthcare, education and care of the elderly. … Another problem … concerns overall political legitimacy. … A third problem concerns the need for work. … The basic error with the idea of unconditional basic income is its unconditionality. …

On the 11th December a response appeared: ‘Universal Basic Income: Definitions and details’:

… The main problem with the UBI that Rothstein discusses in his article is not its unconditionality: it is the detail and the flawed definition. … a UBI is an unconditional income paid to every individual. The definition implies neither a particular amount, nor that means-tested benefits would be abolished, and it does not imply that the UBI would free people from paid employment. So instead of a UBI scheme that pays £800 per month to every individual, and that abolishes means-tested benefits, let us instead pay £264 per month to every individual (with different amounts for children, young adults, and elderly people), and let us leave means-tested benefits in place and recalculate them on the basis that household members now receive UBIs. According to research published by the Institute for Social and Economic Research at the University of Essex, the effects of such a UBI scheme would be interestingly different from the effects of Rothstein’s. …

More information at:

Bo Rothstein, “A bad idea for the welfare state“, Social Europe, 23rd November 2017

Malcolm Torry, “Universal Basic Income: definitions and details“, 11th December 2017