by Andre Coelho | Feb 12, 2019 | News

Masked Narodi supporters, in 2014. Picture credit to: Aljazeera

Just a few days after Rahul Gandhi, leader of the Congress Party, announced the intention of implementing a “nationwide minimum income for the poor”, Prime Minister Narenda Modi’s government now proposes a “basic income for poor farmers”. This policy was set as a part of a supposedly interim budget, only up to the elections date (May 2019), although in this case expenditure was scheduled up to December 1st 2019, in a clear bet to win these elections and continue in power.

The cited interim budget was presented by (acting) finance minister Piyush Goyal, and the “basic income for poor farmers” is expected to affect millions of small farmers, who will be paid 6000 Rupees per year (84 US$/year), in principle as an unconditional cash transfer. 6000 Rupees averages around 3% of a typical family yearly net living wage (~183000 Rupees), and 6% that of a single adult (96900 Rupees). It is inferred that the hand-out to farmers would be to the farmer, as the owner of the land parcel, hence to his/her family. In this context, the policy promise is not individual (only if the farmer is single and has no dependent children), nor enough to cover minimum necessities (not basic), nor universal (only for farmers). The “basic income” term, therefore, is used by Modi’s government in a very loose manner, which might indicate more of an intent to get an electoral edge, particularly over the latest Congress proposal.

There is a general acceptance in India that transferring money directly to poor people avoids the corruption of the current subsidies system, and so such a policy as a kind of basic income makes sense to many. Unemployment is another important issue, but, interestingly enough, this might be ameliorated by the implementation of a basic income (type of policy), according to Gareth Price, from the Chatham House think tank. This is because direct, unconditional money in the pockets of people will most likely drive an economic expansion. Despite this reasoning, in other allegedly developed nations, such as France, the ability to work in paid jobs is still seen as central to the social contract. There, policy makers are more afraid people will just sit back and give up on contributing with their work to society, than they are confident that basic income will help those at the bottom of the income scale to fully participate in the economy, as workers and consumers.

More information at:

André Coelho, “India: Basic income is being promised to all poor people in India”, Basic Income News, February 1st 2019

Adam Withnall, “India budget: Modi announces universal basic income for farmers in bid for rural vote ahead of elections”, Independent, February 1st 2019

Expenditure and Living Wage calculation in India

André Coelho, “France: Law proposal to experiment with basic income rejected before even discussed”, Basic Income News, February 10th 2019

by Karl Widerquist | Feb 6, 2019 | Opinion, Research, The Indepentarian

When people ask me where to find empirical research on the effects of Basic Income online, I tend to recommend the following sources, both for the sources themselves and for the many more sources you’ll find in their bibliographies:

Karl Widerquist A Critical Analysis of Basic Income Experiments for Researchers, Policymakers, and Citizens, Palgrave Macmillan, December 2018. In case you can’t find my book at your university library, I posted an early draft of it (and as far as I know everything I write) for free on my personal website.

Karl Widerquist “A Failure to Communicate: What (If Anything) Can we Learn from the Negative Income Tax Experiments?” The Journal of Socio-Economics (2005). You can find an early free version here.

Calnitsky, D. (2018) ‘The employer response to the guaranteed annual income’, Socio-Economic Review, 25, 75–25.

Kangas, O., Simanainen, M. and Honkanen, P. (2017) ‘Basic income in the Finnish context’, Intereconomics, 52, 2, 87–91.

Karl Widerquist, “The Cost of Basic Income: Back-of-the-Envelope Calculations,” Basic Income Studies, 2017. Again if you don’t have access through your university, you can find an early version of The Cost of Basic Income on my personal website.

“Basic Income: An Anthology of Contemporary Research” is helpful, although only a small part of it is empirical.

Widerquist, K., Howard, M. (Editors) Alaska’s Permanent Fund Dividend: Examining Its Suitability as a Model and Exporting the Alaska Model: Adapting the Permanent Fund Dividend for Reform around the World, two books both published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2012. Contact the editors (karl@widerquist.com) if you have trouble locating the books.

Evelyn Forget, “The town with no poverty: The health effects of a Canadian guaranteed annual income field experiment,” Canadian Public Policy, 2011

Go to Google Scholar: search “basic income” and/or other names for the concept with our without additional key words to narrow it down. Scroll through as many pages of links as you have time for.

Go through the tables of contents for each issue of the journal Basic Income Studies.

Go through the news on Basic Income News, as far back as you have time for, looking for mentions of and links to new research.

Go to the “Basic Income FAQ/wiki,” on Reddit and look for the empirical articles.

I’m leaving out a lot of good stuff because I can’t find it online, but those things together should give you a good idea of the current state of UBI research.

What links would you add (please answer only if you can give the full information about it including an actual links to it)?

by Andre Coelho | Feb 2, 2019 | News

Minho, Portugal. Picture credit to: Notícias ao Minuto

Last Wednesday there was a Conference on Basic Income at Universidade do Minho, called “Rendimento Básico: uma Ferramenta para uma Europa Social? [Basic Income: a Tool for a Social Europe?]”. It was organized by Centro de Ética, Política e Sociedade [Center for Ethics, Politics and Society] (CEPS), together with several institutional partners, for instance Universidade do Porto (Porto University) and Ministério do Trabalho, Solidariedade e Segurança Social (Social Security, Solidarity and Work Ministry).

This Conference featured presentations and contributions from several specialists, politicians and students, such as Philippe van Parijs, Jurgen de Wispelaere, Jamie Cooke, Evelyn Forget, Roberto Merrill, Gonçalo Marcelo, José António Vieira da Silva (Social Security, Solidarity and Work minister) and Ana Carla Pereira (European Commission Social Protection Systems Head of Unit), among others.

On the aftermath of this event, several interviews and articles were published, confirming the rising interest in basic income within the Portuguese reality. Interviewed by Público newspaper, van Parijs clarified that, although automation is largely seen as the prime mover of basic income, at least in “developed” countries, it is “not at the bottom of the basic income proposal”. According to him, basic income is, rather, a way to include everyone in work. Answering a series of questions focused on the perceived problems with basic income – work disincentive, contrary to work ethic, social cleavages, menace to the welfare state – van Parijs defended the proposal as non-conflicting with the work ethic, since people can choose better what to work for with a basic income, and also as collaborating with the welfare state and its function to provide material security.

Minister Vieira da Silva, also interviewed by Público, believes that basic income, if ever to become a reality, can only be implemented at an European scale. His greatest fear is that, with basic income, society will become polarized between the employed, who would (in his view) be financing basic income, and the unemployed, who would only be surviving on that unconditional stipend. He also claims that basic income experiments “have not been very successful”, and that basic income in Portugal “seems an option still far away from implementation”. The minister has not justified any of these assertions, which may unveil doubts on his knowledge about the successful experiments already undertaken (e.g.: India, Namibia, Canada), and the most recent events in India related to unconditional cash transfers. Nevertheless, Vieira da Silva acknowledges that in an era of robotization, basic income can be seen as an investment, “guaranteeing access to consumption for everyone”.

Ex-Work and Solidarity minister, Paulo Pedroso was also interviewed in this sequence of opinion on basic income. To Pedroso, people should simply not be exempted from their duty to contribute to society. However, he also acknowledges that creating a financial floor which eliminates the possibility of not having enough resources to live with dignity, is a good idea. Hence, he supports universality, but not unconditionality. More, according to Pedroso, basic income “aims to replace the welfare state”, which is an opinion shared by many on the Left on the Portuguese political spectrum, namely Francisco Louçã. The ex-minister assumes that the implementation of a basic income in Portugal will demand so much financial resources that the government would be forced to cut on essential services, like education and health, although that has aldready been proven unnecessary. Pedroso’s views on basic income do not come as a surprise, though, as he already had delivered his opinions before, having then stated that basic income “amounts to suicide”.

Discussions in Portugal about welfare, taxation and, ultimately, basic income, do not seem to share a rational basis. From several interviews it becomes clear that opinions get formed on emotional grounds – particularly fear and hesitation – and not over evidence. However, the conversation continues, in the midst of international experimentation (with basic income-related policies) and tentative implementation moves (India).

More information at:

[in Portuguese]

São José Almeida e Sónia Sapage, “O rendimento básico incondicional é um remédio para a armadilha do desemprego [Basic Income is a medicine for the unemployment trap]”, Público (online), January 27th 2019

Tiago Mendes Dias, “Para Vieira da Silva, o rendimento básico deve ter uma escala europeia [To Vieira da Silva, basic income shall have na european scale]”, Público (online), January 24th 2019

Sónia Sapage, “O Rendimento Básico Incondicional ainda não passou da fase da utopia [Basic Income has not yet passed the utopian phase]”, Público (online), January 29th 2019

André Coelho, “Portugal: Basic income event attracts politicians and social science experts”, Basic Income News, Mat 28th 2017

by Andre Coelho | Jan 24, 2019 | News

The structure of the Conference has been updated.

BIEN Civic Forum will be held on the 22nd of August. On this day, having been called “India Day”, two major plenary discussions will be held: one that focuses on the Indian state of Telangana and its policy initiatives related to basic income, and a second one about the more general debate at the Indian national level.

As for the Thematic Areas for Plenary Sessions, these have been improved and detailed, as follows:

- Ideological Perspectives and Diverse Worldviews on Basic Income

Exploring different ideological perspectives and worldviews that see an unconditional Basic Income as a desirable component of a more equitable and inclusive society

- Women’s Care and Unpaid Work: Is Basic Income an essential component of a new paradigm of Equity?

What implications and impact would basic income have on the lives women who constitute more than half of the global population? Can we talk of a sustainable society as long as we steal labor from women? Can an unconditional basic income remedy this structural inequity?

- Is Basic Income the Foundation of a Caring Economy and Society?

Is it possible to build an economy and a society that is based on values of caring, sharing and partnering rather than power, domination and control? Is an unconditional basic income an essential ingredient of such a society?

- The Emancipatory Potential: What forms of Freedom and what kind of Community Life does Basic Income promote?

Basic Income experiments across the world have demonstrated repeatedly that an unconditional basic income has a strong emancipatory effect of its recipients. It loosens the constraints of existence and liberates the mind to seek a life and a community better than what we have now. What implications does this freedom and emancipation have on us and the communities that we dwell in?

- Basic Income, the Commons and Sovereign Wealth Funds

Our society privileges and celebrates private inheritance, but it equally turns invisible what can be called our public inheritance, and the fact that it is people who own natural resources and the state is just a custodian. This perspective if implemented can radically transform the way we view, manage and account for our natural wealth and endowments.

- BI Pilots: Opportunities and Limits of Evidence

In both the low-income countries and in high-income countries, there have been basic income pilot studies. While we already have the results of some of the studies, by mid-2019, we are likely to have more results. The Congress will deliberate both the results and also what they can achieve in terms of policy change

- Basic Income and Political Action: What does it take to transform and idea into policy?

It is one thing to have strong evidence from pilot studies and something else to get the acceptance of the policy makers and persuade them to act on it. There have been some pioneers among politicians and policy-makers across continents who have taken the plunge and implemented different versions unconditional income transfers, inspired by the spirit of the idea of basic income. Do we see them as first steps towards a full UBI? Or as distortions of the idea?

- Development Aid and Corporate Philanthropy: Is Basic Income a Better Paradigm and Way Forward?

In recent years, there has been a great deal of rethinking about the effectiveness of the current paradigms of giving aid either to countries or to communities. Unconditional Basic Income is increasingly emerging as a radical alternative to conventional notions of giving aid. We witness this shift as much within the UN think-tanks as that of corporate philanthropy.

As for thematic areas for concurrent sessions have been updated and completed:

- Ideological Perspectives on Basic Income

- Women’s Care and Unpaid Work: Is Basic Income the new paradigm of Equity?

- Basic Income in Development Aid Debate: Is there a Paradigm-shift?

- Religious Perspectives on Basic Income

- Basic Income as a Foundation of a Caring Economy and Society?

- What forms of Freedom and What kind of Community Life does Basic Income promote?

- Basic Income and Blockchain Technology: Are there Synergies?

- Basic Income, Poverty and Rural Livelihoods

- Basic Income, the Commons, and Sovereign Wealth Funds: Is Public Inheritance an emerging issue?

- Basic Income Pilots: Opportunities and Limits

- Basic Income and Political Action: What does it take to transform an Idea into Policy?

- Basic Income and Corporate Philanthropy: Is Basic Income a better paradigm and way forward?

- Basic Income and Children

- Basic Income and Mental Health

- Basic Income and Intentional Communities: What does this Experience Teach us?

There will also be a Short Films Exhibition, organized in partnership with Grundeinkommen Television (Gtv), which a is part of the Initiative Grundeinkommen, a pioneering civil society initiative established in 2008. Guidelines for submission:

- The length of the Film should be below 15 minutes;

- Your film should be made in 2018 or 2019 and be shown for the first time to a wider audience at the Congress;

- The film should be in English or with English subtitles;

- Entries should reach latest by 1st June 2019;

- A committee appointed by INBI will select the entries for exhibition at the Congress;

- Two of these selected films will be jointly rewarded INBI Short Film Prize of 500 US Dollars each.

For further information and to submit films, please contact Enno Schmidt, Chair of the Committee. ennoschmidt@me.com.

General registrations can be made here. For paper abstract submission (in MS Word document between 300 and 500 words), please email to: 19biencongress.india@gmail.com.

The Congress is supported by:

LocalHi – travel and logistics

NALSAR University of Law

SEWA Madhya Pradesh

WiseCoLab

Mustardseed Trust

Everyday.earth

OpenDemocracy

CEPS, Center for Ethics, Politics and Society

Gtv, Grundeinkommen Television

by Andre Coelho | Jan 21, 2019 | News

Road in rural India. Picture credit to: India TV.

Farmers in India are under considerable stress. Uncertainty regarding weather, yield, prices and revenue, create the perfect conditions for distress and fragility over the exposure to shark lenders. That also means that massive hunger is a risk just around the corner, and in a year of elections in India, its rural population (about 70% of total population) is repeatedly targeted for campaign purposes. Loan waivers, for instance, have been a pet political tool for election purposes, even though waivers haven’t traditionally helped small or marginal farmers (around 80% of all farmers).

To counteract this state of affairs, some states in India start to take matters in their own hands. The province of Telangana has been the first Indian state to provide and unconditional cash transfer to farmers. This, the decision of the Sikkim state to go forward with basic income implementation, experimentations popping up in several parts of the world (e.g.: Germany, Ukraine, United States, Spain), and some political support for basic income over central government in New Dehli, particularly after the 2016-2017 economic survey and its famous chapter on basic income, leads to renewed conversations in India.

In programs like this one, provocatively titled as “Government mulls universal basic income, is India ready for income for all?”, obstacles to basic income seem more in number and in size, than opportunities and benefits it can potentially provide. TV pundits take turns at criticizing the idea: it disincentivizes work, it is unaffordable, it is vague and populist, it cannot possibly be a replacement for long-time and traditional forms of help to those in need. However, simultaneously, some high placed economists and politicians see at least some advantages and viability in a basic income for all Indians, or directed to certain population cohorts (such as farmers). The dice are rolling.

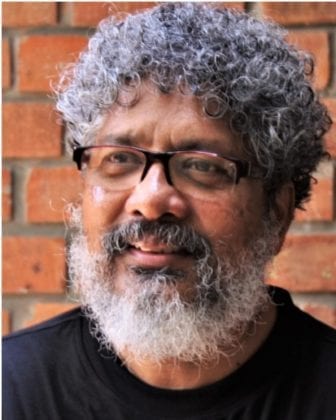

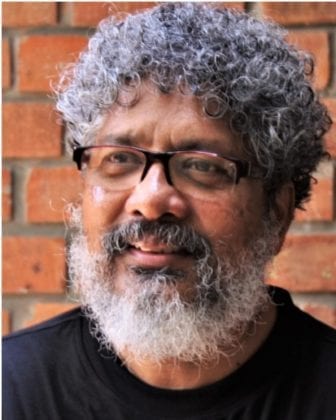

Sarath Davala. Picture credit to: BIEN

Sarath Davala, coordinator at India Network for Basic Income (INBI), has written on Facebook: “Increasingly I am beginning to think that India could be the first country to take the plunge into a kind of Targeted Basic Income. It won’t be universal, but it will certainly be unconditional. The initiative is more likely to come from the provinces”. Guy Standing, also a long-time activist and researcher on basic income and someone who has been deeply involved in the Indian (basic income) experiments, has also pronounced himself at the onset of India’s first steps towards this revolutionary policy: “The beauty of moving towards a modest basic income would be that all groups would gain. That would not preclude special additional support for those with special needs, nor be any threat to a progressive welfare state in the long-term. It would merely be an anchor of a 21st century income distribution system. Will the politicians show the will to implement it? We need to see”.

More information at:

“Why Telangana gave cheques to farmers instead of direct transfer”, rediff Business, May 11th 2018

André Coelho, “India: Sikkim state is on the verge of becoming the first place on Earth implementing a basic income”, Basic Income News, January 11th 2019

Guy Standing, “Basic income works and works well”, The Hindu, January 14th 2019