by Kate McFarland | Jun 15, 2016 | News

The Australian Pirate Party has officially endorsed a “basic income policy” (more precisely, a negative income tax), according to an announcement published on June 14th, 2016.

In the announcement, Sam Kearns and Darren McIntosh — New South Wales senate candidates from Pirate Party Australia — elaborate on the need for a basic income, focusing on concerns about automation, the “inefficient, patronising and punitive bureaucracy” of Australia’s current welfare system, and the advantage of basic income in facilitating care work as well as new business and innovation.

As described in the party’s Wiki, the policy is a negative income tax designed to result in a minimum income of $14,062 per year for adults (aged 18 and over) who have completed school. This baseline amount would be “topped up” in certain cases, including parents, caregivers, aged and disabled persons, veterans, and low-income earners who lack public housing.

Pirate Party Australia was founded in 2008 and legally recognized by the Australian Electoral Commission in 2013. According to Wikipedia, it claimed approximately 1300 members as of 2015.

by Jason Burke Murphy | Jun 10, 2016 | Opinion

I have been part of Basic Income Earth Network’s and US Basic Income Guarantee Network’s social media team for a while and I want to clarify something for as many readers as possible. There are three ways of looking at the basic income movement: Basic Income can be endorsed as a (1) proposal or (2) a project or (3) an idea. A lot of communication causes people to evaluate each other more harshly than they need to because they mistake where the speaker or writer is coming from.

I will say what I mean and show how this distinction helps me.

(1) Basic Income as Proposal: When I describe basic income as a proposal, I am referring to any bill or law that implements an unconditional grant. Here we are looking at the policy. Here are some US-based examples:

Alaska invests a small amount of the land rent it charges and puts out the dividend to every citizen. They give about $2,000 to every individual and $8,000 for a family of four.

The Healthy Climate and Family Security Act would put a cap on carbon, charge fees, and distribute the revenue to everyone. This would amount to about $1,000 per person and $4,000 for a family of four. (Ref. www.climateandprosperity.org)

The Fair Tax act gets rid of the income tax and replaces it with a national sales tax. They acknowledge that this move would hurt low-income people so they include a dividend for all. They list around $7,200. (https://fairtax.org/)

An interesting common feature of these three examples is that basic income was an afterthought for many supporters. These proposals are not parts of projects that seek to abolish poverty or secure independence for all.

The Alaskan Governor at the time the dividend was implemented, Jay Hammond, was following the basic income movement and he sought a more substantial amount. Alaska, however, has never had a basic income movement. There has never been an attempt to push the grant all the way to a poverty-ending amount. That said, at $2,000 a year for all family members, the Alaskan Permanent Fund raises the incomes of low-income families more than most other proposals out there. The dividends were largely an accidental product of the State’s Constitution, which gave un-owned land to the State. If power-brokers in Alaska had known that this land included some of the most lucrative oil reserves in the world, this would not have happened. Hammond’s commitment combined with these fortunate circumstances produced the Alaska Permanent Fund.

Supporters of the Healthy Climate and Family Security Act are mainly trying to develop an answer to the threat of climate change. They understand that a cap on carbon would raise prices on fuel and other things that many low and moderate income people need. Some supporters are enthused about the dividend to be sure, but it is very seldom sold as a stepping stone for a dividend high enough to foster independence. Again, with that said, there are very few proposals that would result in an increase in average income of $1,000 in low-income communities.

Fair Tax supporters are primarily focused on getting rid of the income tax. The dividend is seldom emphasized in their literature. When it comes to the impact on poverty, the math is more complex for this proposal, because the new sales tax would be high. Proponents do cite economists who stress that the Fair Tax would have a progressive impact.

When Basic Income Earth Network or US Basic Income Guarantee Network links to an article describing a project like this, we get a lot of comments that evaluate them as if they were the entire basic income project. The proposal is treated like a project. We are informed that you cannot live on $2,000 a year. We know that. Many respondents “project” projects onto proposals. They don’t evaluate the proposal but an imagined series of other proposals that would stem from an imputed project. When Silicon Valley investors start a basic income pilot, we are told that they want to cut this and that. But they have not said so, and we will not know their project until they start making concrete demands.

Lots of media presume that a basic income replaces all other social provisions, which is a view that I have only rarely encountered in my time with engaged members of USBIG and BIEN. We hear a lot of false news that Holland or Finland is replacing everything with BI. Projects are being foisted onto proposals and policies.

Keep in mind that a basic income may well be implemented as an afterthought or as a part of a project that most anti-poverty activists oppose. Charles Murray’s proposal would consist of $10,000 per person and a $3,000 health care voucher. This would replace everything that currently promotes social protection. When he emphasizes the amount of money this would save, that includes bureaucratic expenses, but that also entails a huge withdrawal of other expenses, such as social provisions that many anti-poverty activities would rather keep .

While we should not endorse a bill that implemented Murray’s proposal, we can acknowledge the grant is a good idea if it is not accompanied with harmful cuts. If such a basic income were to be implemented (and Paul Ryan has expressed an interest in consolidating anti-poverty provisions), those who support BI as part of an anti-poverty project will have to fight to keep the grant and raise it. We have to talk about basic income now so that anti-poverty activists do not oppose it.

(2) Basic Income as Project: Once a basic income is part of a project, we have to look at what the whole project seeks to do. Many of the supporters of basic income pilots in Finland also support austerity as the right response to the European financial crisis. Almost everyone involved with Basic Income Earth Network and its affiliates are opposed to austerity. They see basic income as a way to combat poverty directly, with less bureaucracy and more security for most citizens. Many supporters of basic income in Finland are working to make sure the pilots are an opportunity to push basic income as emancipatory .

How it is funded, what is cut, what is not cut—all of these factors turn a policy item (an unconditional cash grant) into a project. We have to learn how to assess whole projects.

Left-wing organizations should make a basic income part of their left-wing project. Left-wingers that denounce basic income as “neo-liberal” are refusing to de-link the policy from a rival project. They should write out what sorts of basic income they would support and condemn the powers-that-be for not securing economic independence for all.

Free-market enthusiasts (I am not calling them “right-wing”) should make a basic income part of their free-market project. Those that denounce a basic income as “socialist” or “communist” are refusing to de-link the policy from a rival project. They need basic income if they care about extending the benefits of markets to everyone.

In the US, there are no left-wing or free-market organizations (or magazines or parties) that have stated clearly whether or not basic income is part of their project. My hypothetical left-wingers and free-marketers are based on reading a few thousand Facebook comments and individual columnists.

De-linking the proposal from the project can be difficult. Would an otherwise free-market-oriented economist with a basic income in the mix still be “left-wing”? Is basic income such a good policy that we should support someone who supports a rival project? Some people are suspect of an Alaska-style dividend just because they know the state usually votes Republican.

These are the sort of choices we will face. If a supporter of a rival project embraces basic income, one has to decide whether or not to jump ship. Some basic income supporters will want to work within other projects. Some will work within the Greens or within Socialist or Labor or Environmental organizations. Others might name a particular bill and lobby for it.

Basic Income Action in the US has stated that they seek any unconditional grant that leaves the least-well-off and the majority with more income than before. They have lobbied for the Healthy Climate and Family Security Act and hope to get a bill sponsored that has a full-fledged basic income in mind. BIA argues that this project improves any other project. Whether they are the left or the right, whether they have a good tax plan or a bad one in mind, they would be that much better with a basic income in the mix. See them at www.basicincomeaction.org.

(3) Basic Income as Idea: There is another way to think about basic income. This is an idea that gets in your head. Once you realize that it is mostly a question of political will, you start to think about how different the world would be if everyone had a share. You start to wonder how different schools would be. How different political life would be. How different the art world and the sport world would be.

(3) Basic Income as Idea: There is another way to think about basic income. This is an idea that gets in your head. Once you realize that it is mostly a question of political will, you start to think about how different the world would be if everyone had a share. You start to wonder how different schools would be. How different political life would be. How different the art world and the sport world would be.

When I first heard about basic income, I was excited because I saw it getting to people who need it. I had seen the manipulation of money and power deny the invisible and the powerless the resources they need. Too many times I saw “jobs programs” pretend to hire “everyone who sought work.” Sports arenas and lectures were sold as anti-poverty programs. A basic income gets around all that. Now, I think more about how much more powerful low-income communities will be. And I see better the work they are already doing.

Sarath Davala, Renana Jhabvala, Soumya Kapoor Mehta, and Guy Standing organized a pilot program in India and wrote a book that testifies to its emancipatory effects. A video they made provides a nice synopsis. One sees here an image of strong people made more powerful.

I see the same impact in low-income parts of the US. Basic income gets around the pretending so many people do when they approach poverty. I wrote a piece on how a basic income could work in the Saint Louis/Ferguson area that has this sort of emancipation in mind. One of my main goals was to get readers to just see what a difference more income would make. We should spare them the hectoring about each and every choice they make and issue a share.

The Swiss Basic Income Movement mostly sought to push basic income as an idea in Switzerland but also all over the world. History’s largest poster posed the question: What Would You Do If Your Income Were Taken Care Of? They posed it in English and reassembled the poster in Berlin . A picture of the poster was shown in Times Square. They are posing a question to the world.

The movement has pushed people to think about what makes a life and a society good. Long before basic income becomes a policy, it does great work as an idea.

Another example is the Canadian Association of Sexual Assault Centres. Their shelters talk with residents about basic income. They have a copy of the Pictou Statement they wrote in which they proclaim their support for basic income.

The statement calls on some of the most vulnerable people in the world to think about how different things would be if everyone had a share:

“We refuse to accept market measures of wealth. They make invisible the important caring work of women in every society. They ignore the well-being of people and the planet, deny the value of women’s work, and define the collective wealth of our social programs and public institutions as “costs” which cannot be borne. They undermine social connections and capacities (social currency).”

Publicly endorsing basic income offers a chance for different relationships between people. When a shelter tells someone fleeing assault that they want a different allocation of resources, this breaks the long chain of bureaucrats, landlords, advisors, and hustlers. When I tell someone that I think they deserve a share, I have a chance to show that I recognize them as valuable. That is a powerful idea.

I have also found that people who are not sure they believe basic income is feasible politically end up pointing to other social provisions that they consider more efficient or politically feasible. They start to talk about education and health and public employment. This is a far better conversation than one that argues between some provisions and no provisions, which is the one we are hearing far too often. That is a powerful idea.

A lot of people have seen police violence, corruption, and the privileged position of the wealthy, and they just can’t imagine a government that macro-manages and micro-manages a just economy. However, they have seen Social Security issue a check to everyone and they have seen the IRS tax forms issue an exemption. They know that this proposal is simple enough for even a bureaucratic government to implement. That makes this a powerful idea.

Lots of people are saying that they think basic income is great, and then they get challenged to produce a proposal or to spell out their project. I want to see more basic income policy proposals out there. I want to see more people make basic income part of their projects. But we also need to see people saying “The world be better if we did this.” We need to get as many people as we can to say “That’s a powerful idea.”

by Stanislas Jourdan | May 22, 2016 | News

The first EU-wide opinion survey on basic income finds a great majority of Europeans know about basic income and are supportive of the idea.

While it is no surprise that basic income has gained a lot of popularity over the past few months, it is difficult to grasp exactly how mainstream basic income has begun. That’s where opinion polls can help.

In Europe – where most of the political developments are happening in Finland, the Netherlands, and France – a new poll survey shows the magnitude of the trend – and it’s very encouraging.

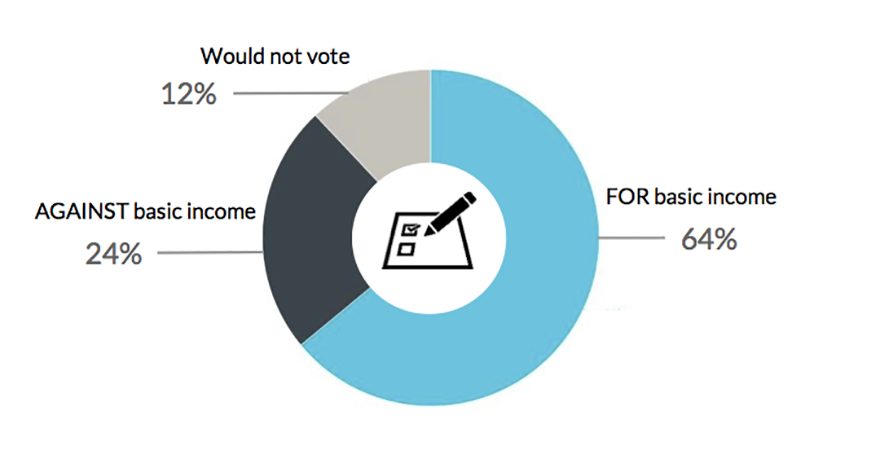

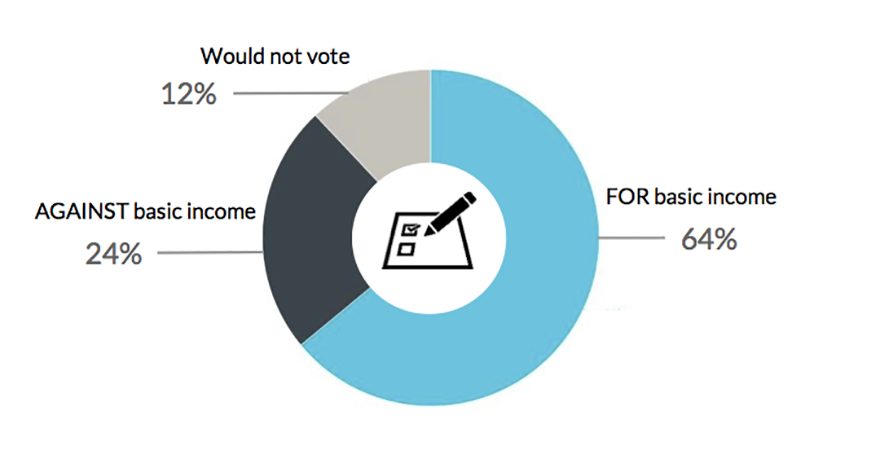

According to the preliminary results (pdf here) from a survey carried out in April 2016, about 58% of the people are aware of basic income, and 64% would vote in favour of the policy if there was a referendum about it.

The survey was produced by the Berlin-based company Dalia Research, within the framework of its research programme called e28TM, a European-wide survey, to find out “what Europe thinks.” The e28TM is conducted every 6 months within a sample of 10,000 people, representative of the EU (28 countries) population. The respondents were invited to an online survey via their smartphones, tablets or computer desktops without knowing in advance the topics of the poll. Last April, the survey included basic income.

In the questionnaire, basic income was defined as “an income unconditionally paid by the government to every individual regardless of whether they work and irrespective of any other sources of income. It replaces other social security payments and is high enough to cover all basic needs (food, housing, etc.).”

Only 24% of the respondents said they would vote against it, while 12% would not vote. More interestingly, though, the results show a correlation between the level of awareness about basic income and the level of support. In other words, the more people know about the idea, the more they tend to support it:

According to the survey, countries where basic income is most popular are Spain and Italy (with 71% and 69% of respondents, respectively, inclined to vote for a basic income).

However, those results are not entirely accurate as they do not show results for smaller countries where the population being interviewed was too small for the results to be statistically significant.

Respondents were also asked about their biggest hopes and fear if a basic income was to be introduced. It turns out the most convincing arguments in favor of basic income were that it would “reduces anxiety about basic financing needs” (40%) and improve equal opportunity (31%). Perhaps the most surprising result is that the downsizing of bureaucracy and administrative costs was considered the least convincing argument (16%).

Only 4% of the people would stop working.

On the other hand, the most frequent fear or objection was that basic income would encourage people to stop working (43%). However, the survey also provided evidence that this would not in fact be the case — with only 4% of the respondents saying that they would stop working if they had a basic income. Moreover, only 7% said they would reduce their working time, while another 7% said they would look for another job. About 34% of the people surveyed said basic income would “would not affect my work choices” while another 15% said they would spend more time with their family.

This confirms the result of a previous poll conducted in Switzerland in January that a great majority of people want to work, despite having their basic needs met anyway.

Besides the apparently unfounded concern that people would stop working, other objections considered convincing were that people would massively immigrate (34%), that basic income is not affordable (32%) and that only the needy should receive assistance (32%).

Overall, those results are very positive for basic income. They finally provide evidence that basic income has become mainstream and is likely to be supported by a majority of the population – at least in the EU.

While a number of national polls have already found a good level of support for basic income in France (60%), Catalonia (72%), and Finland (67%), Dalia Research is the first to have produced a European-wide survey on the popularity of basic income.

by Kate McFarland | May 20, 2016 | News

Although a universal basic income is likely to be conceived in the public eye as a utopian dream of the left, its proponents are often keen to note the idea’s historical appeal across the political spectrum, citing its support from the likes of Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek.

Nor is basic income off the radar of the contemporary right. Indeed, the idea recently received some discussion on the blog of the noted conservative publication National Review — with Iain Murray, Vice President of Strategy at the Competitive Enterprise Institute, tentatively endorsing the idea. (The CEI is a think tank that describes itself as “dedicated to free enterprise and limited government.”)

In a short post, Murray responds to Michael Strain of the conservative American Heritage Foundation, who published a critique of basic income in the same blog as well as the Washington Post — ultimately coming down against the idea despite admitting several of its appealing features, such as reducing bureaucracy and removing the stigma associated with receipt of government aid.

Murray claims, contra Strain, that a basic income would not problematically dis-incentivize work — unlike the current system of welfare in the United States — and that, on the contrary, it would empower many people to contribute more productively to the economy. He also contends that a UBI would encourage charitable giving.

Granted, Murray does emphasize two caveats: a UBI might just become an add-on to an overblown welfare state, and “it still relies on robbing Peter to pay Paul.”

Despite Murray’s reservations, his tentative endorsement merits attention by other proponents of a free market and limited government, those who might otherwise scoff at a policy sometimes flippantly caricatured as “the government giving away money for free.”

Iain Murray, 4 April 2016, “Tentatively for Universal Basic Income,” National Review: The Corner.

Image Source: Annwong1026 (via Wikimedia Commons)

by Tyler Prochazka | Apr 18, 2016 | Opinion

Just because someone is disabled doesn’t mean they’re any less of a person. Most disabled individuals can still work jobs, get into Disabled Dating, have families, go places, etc. However, society has a tendency to discriminate against them and doesn’t offer disabled the same treatment as able-bodied individuals. Is basic income guilty of this too? That’s what we shall be discussing in this article.

The Universal Basic Income movement continues to pick up steam around the world, with reports that Finland is interested in starting its own UBI pilot program, joining a growing list of countries around the world. Still, many important questions surround the details of a basic income system.

One criticism raised even by some supporters is that many recent discussions of the UBI have overlooked the disabled and chronically ill. This is not the first case of discrimination against people with disabilities to affect the U.S financial system. While disabled people are always able to take out disability insurance from somewhere like https://www.leveragerx.com, there is no reason why they should be left out of the Universal Basic Income plan.

For example, in its groundbreaking UBI report the Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA) mentioned disability only to say specific benefits for the disabled were excluded from its model. This is something very important to the disabled community, many of whom click here to get information about their long-term options.

This silence has led some commentators to be skeptical of the UBI’s ability to accommodate the specific needs of disabled individuals. In an article recently published in the Independent, one critic worried that a basic income would either be too low to assist the disabled or too high to be affordable.

Critics are right to point out those who need special assistance are an important consideration when constructing a UBI scheme.

Fortunately, there are ways to integrate these concerns into UBI models while largely retaining the program’s simplicity.

For instance, an additional supplement for the disabled could be granted based on the severity of the disability. The current structure and eligibility requirements for disability insurance from the U.S. Social Service Administration could be utilized to determine the amount of additional aid.

There are three potential options for such a supplement:

- Provide a simple cash transfer that will allow the individual to spend the money accordingly.

- Provide a cash transfer to an account modeled on the Health Savings Account (HAS) structure. HSAs restrict account purchases to medicinal goods and services, but an individual can generally purchase these goods and services from any provider they see fit. This structure may capture the best of both worlds; it would prevent fraud given that those who are not truly disabled would be unlikely to apply for a supplement that is restricted to purchasing goods and services needed for disabled individuals, while also retaining account holders’ flexibility in choice of private providers.

- Expand in-kind services that cater to disabled individuals. While specific in-kind services that should be expanded are beyond the scope of this article, it is almost certain that existing federal and state services for the disabled would not be altered if a UBI was implemented.

Regardless of which option is chosen, none of them make the UBI “utopian” as some critics have recently charged. By adapting existing governmental structures, policymakers can create a UBI while also making special accommodations for those citizens who do need additional supplements to the basic income. Such a system would still be much simpler than the existing structures of government assistance. In the United States, for instance, the vast majority of the current social services bureaucracy could be eliminated and replaced with a streamlined system that looks at only age and health/disability status to determine the size of the benefit. In fact, for those with invisible disabilities, a UBI would likely be a vast improvement to the current situation.

So far, critics have come up short in offering compelling reasons why accommodating those with special needs will drastically undermine the efficacy of UBI models. Nonetheless, they do raise an important concern, and the UBI movement must make room for discussion regarding how to integrate these needs into the basic income.

(3) Basic Income as Idea: There is another way to think about basic income. This is an idea that gets in your head. Once you realize that it is mostly a question of political will, you start to think about how different the world would be if everyone had a share. You start to wonder how different schools would be. How different political life would be. How different the art world and the sport world would be.

(3) Basic Income as Idea: There is another way to think about basic income. This is an idea that gets in your head. Once you realize that it is mostly a question of political will, you start to think about how different the world would be if everyone had a share. You start to wonder how different schools would be. How different political life would be. How different the art world and the sport world would be.