by Genevieve Shanahan | May 12, 2017 | Opinion

David Piachaud, Emeritus Professor of Social Policy at the London School of Economics, last November put forward a four-pronged case against basic income – on the grounds of justice, simplicity, economic efficiency and political feasibility. While the argument, I believe, fails on all four counts, I’ll here focus on the justice argument.

To summarize, Piachaud outlines Philippe van Parijs’ famous argument for basic income from his 1991 paper “Why Surfers Should be Fed: The Liberal Case for an Unconditional Basic Income” and claims that the fatal flaw of van Parijs’ argument is that he does not take into account a crucial distinction between the voluntarily and involuntarily unemployed.1 The former value their leisure, it is posited, at least as much as the lowest wage paid to their employed counterparts. In this way, only redistribution of income to the involuntarily unemployed can be justified on Rawlsian grounds. Unfortunately, Piachaud overlooks or underestimates van Parijs’ lucid explanation of why both are entitled to the basic income. In what follows, I’ll try to show why van Parijs’ argument is unaffected by Piachaud’s critique.

The Difference Principle

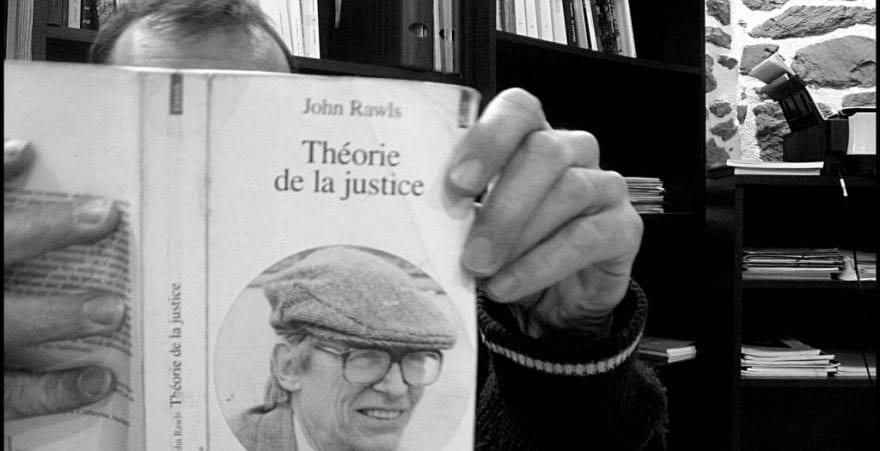

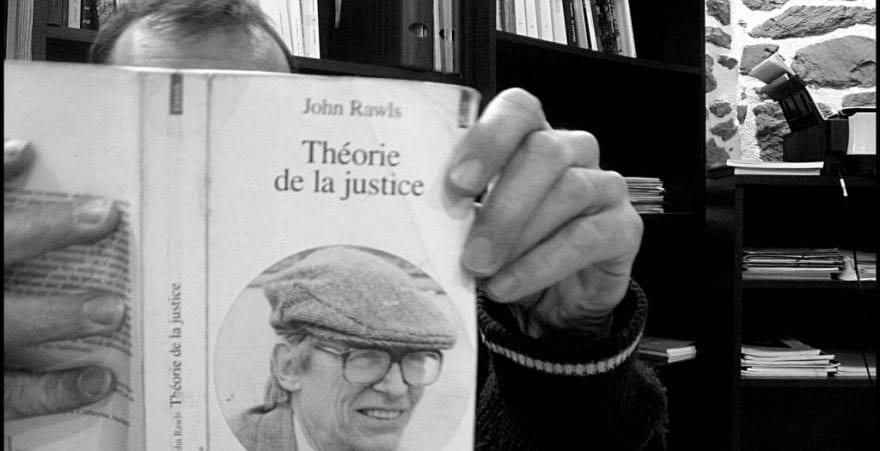

Both van Parijs and Piachaud begin their arguments from the Difference Principle – a key concept in political philosophy since its first presentation in John Rawls’ seminal A Theory of Justice in 1971. Briefly, the Difference Principle states that social and economic inequalities (or inequalities in terms of “primary goods”) are justified only insofar as they benefit the least advantaged. The most important consequence of this principle, on Rawls’ account, is that it justifies inequality in wages to the extent that offering higher wages for valuable work, or steep rewards for successful innovation, incentivises the types of behaviour that generate economic growth and thereby increase the standard of living for all.

A crucial point for the Difference Principle, of course, is determining who counts as “the least advantaged”. One of the first criticisms of Rawls’ theory was that, if the least advantaged are just the people who have the least wealth, it would unfairly favour people who prefer smaller incomes and a lot of leisure over those who prefer to work hard and earn vast sums. If we imagine that the “least advantaged” in our society are those who can only find minimum wage employment (leaving aside other clear forms of disadvantage, like chronic illness and disability, or marginalization), it can seem intuitively perverse to treat those who choose not to take up that minimum wage job as more disadvantaged, and therefore more deserving of public assistance, than those who do. It’s pretty natural to think, “Well, if the surfer doesn’t do the best he can to get that job at McDonald’s, that’s his look out. We can’t be expected to support him when he’s perfectly capable of supporting himself.”

To avoid counterintuitively lavishing taxpayer money on the surfer, then, Rawls proposed that leisure time be treated as a primary good:

“[T]wenty-four hours less a standard working day might be included in the index as leisure. Those who are unwilling to work would have a standard working day of extra leisure, and this extra leisure itself would be stipulated as equivalent to the index of primary goods of the least advantaged. So those who surf all day off malibu must find a way to support themselves and would not be entitled to public funds.”2

This basically gets us to the social welfare system as we (aspire to) have it now: public funds are used to support the least advantaged, who are those who cannot find employment, whether due to incapacity or a lack of jobs. To ensure this support only goes to those who are the least advantaged, conditions and testing are applied – recipients of benefits must prove that they cannot work or that they are actively looking for work. And while basic income advocates often point to the inefficient costs associated with conditionality, such that it may be better for everyone if we just accept and absorb the cost of free-riders, van Parijs points out that people are likely to be willing to forgo efficiency gains to preserve their view of fairness. That is, if we are to gain the requisite political support, we must show that basic income is not merely efficient but also just and fair on a reasonably intuitive view of fairness.

Philippe Van Parijs (photo credit: Enno Schmidt)

Twenty years after Rawls introduced the Difference Principle, van Parijs took this idea and extended it. While most of us basic income advocates aren’t primarily motivated by concern for surfers who can’t possibly take a 9-to-5 job because it wouldn’t leave them adequate time to catch the perfect, most righteous wave, van Parijs’ strategy is strong. If it can be shown that even surfers – capable but unwilling to work – deserve a basic income sufficient to live on, it would seem to follow that everyone else does, too. How, then, does van Parijs get from Rawls’ support for conditional income support to the full, universal, unconditional basic income that would be paid even to the surfer?

Is Leisure Time a Resource?

Van Parijs argues that it is in fact unfair to treat leisure time as a primary good. As a liberal theory of justice – that is, a theory that is neutral regarding what constitutes a “good life” – the Difference Principle should not favour those who prefer working over those with other values. This means that, while we might say that people have to work to pay their own way on the grounds of justice, we can’t say people should work simply because hard work and self-denial is virtuous. Van Parijs shows, by means of a thought experiment, that such discrimination is the result if we follow Rawls and treat the value of leisure time as equivalent to the wage one could earn in the same time if one were working.

This thought experiment involves examining what the consequences of the approach would be in the case of an “exogenous windfall”, such as the state discovering valuable oil and gas reserves off its coast. In the case of such a windfall, the incomes of those who are working or deemed deserving of income support would (ideally3) increase, but the surfer’s set of primary goods would stay the same (i.e., he would have his day of leisure and empty pockets both before and after the windfall). The surfer is thus excluded from the benefits of the windfall – to which he is equally prima facie entitled as a citizen of the state – simply because his leisure time is deemed to be equivalent to the wage earned in a standard working day.

Here Piachaud enters the fray, defending Rawls’ suggestion that the voluntarily unemployed must value their leisure at least as much as the wages they forgo. If the surfer continues to shirk employment at the new, higher wage permitted by the exogenous windfall, the argument goes, it must be because the value of his leisure, to him, was all along at least equivalent to the new higher wage. In this way, the surfer’s share of primary goods continues to be at least equivalent to that of the least advantaged worker.

Piachaud’s argument here relies on a distinction between the voluntarily and involuntarily unemployed, drawn on the grounds of the value of leisure time to them – measured by their willingness or not to take up work where it is available. This is a mistake, however, though one very easily made (I feel its pull constantly in these discussions). It is a mistake because leisure time, like any other primary good, should not be valued at the level of the individual. It doesn’t matter that I value my leisure time a lot and you don’t. What matters is the value of this resource as determined by the market – that is, as van Parijs puts it, “in terms of competitive equilibrium prices.”4 Van Parijs here draws upon another widely influential theorist of distributive justice, Ronald Dworkin, who elegantly shows in “Equality of What? Part 1: Equality of Welfare” that what egalitarians must be concerned with is not equality of happiness, or preference satisfaction, or welfare, but rather equality of resources.5

Let’s illustrate the surfer’s evaluation of his leisure time with a more concrete example. Say I *love* lager. If you hand me a glass of the finest champagne at a party, I’ll hand it back and say “thanks, but please, give me a bottle of lager instead”. If it happened that it was incredibly expensive to make lager, such that one bottle cost $100, I would still buy cases, forgoing many other pleasures. That I live in a world where lager is pretty cheap is lucky for me. But should I be charged more so that the price I pay better reflects its value to me personally? No – that would be unfeasible (how, exactly, would vendors measure each customer’s preferences to ensure they were charging the right price?) and nonsensical (by the same logic, I could pay $5 for the champagne since I only get $5 of enjoyment from it, despite its massively higher market price).

The Costs to Others of Our Choices

This isn’t a simple question of efficiency. What we’re looking for, from a justice perspective, is that no one impose costs on others. It would be wrong from me to pay only $5 for the champagne, despite my personal judgement of its value, because of the vastly greater cost to others of producing it. Dworkin puts it this way – as a matter of justice, “people must pay the actual cost of the choices they make […] measured by the cost to others of those choices.”6

Returning, then, to the distinction between the voluntarily and involuntarily unemployed, van Parijs argues that it is welfarist – that is, mistakenly pursuing equality of welfare rather than equality of resources – to apply willingness-to-work conditions to the basic income. This approach “charges” for leisure time based on whether the able-bodied potential worker enjoys the time off or not (as clumsily measured by Jobcentre assessments of employment search efforts). As we’ve outlined here, the correct price to “charge” for leisure time is its cost to others – the worth of what others might have to give up for us to have that leisure time.

Doesn’t a basic income immediately violate this principle, requiring the rest of society to hand over a portion of their earnings to the voluntarily unemployed? Van Parijs says it does not, because the basic income, fundamentally, is just the individual’s share of the world’s resources he was entitled to from the start, by virtue of being a person.

It should be noted that van Parijs does distinguish between voluntary and involuntary unemployment in a way that affects the level of the basic income. Piachaud and van Parijs both agree that, where there is involuntary employment (i.e. not enough jobs to go around), there are employment rents that are properly subject to redistribution. That is, in a perfectly competitive, idealised labour market – where everyone has access to all relevant information, there are no geographical limitations to what jobs an individual can apply for, and there are no costs associated with hiring and firing, or regulations like minimum wage – supply and demand would balance. Workers’ wages would simply be the actual market price of their labour, and there would be no unemployment attributable to lack of jobs. By contrast, in any real labour market there is friction – due to imperfect access to information, geographical limitations, hiring and firing costs, and regulations – which means that many workers are paid more than would be necessary in a perfect market for their labour, and many eager potential workers are left without a job. In this way, on van Parijs’ account, the level of the basic income can rise and fall in accordance with the level of employment rents in a labour market.

“[…] in the case of scarce jobs, let us give each member of the society concerned a tradable entitlement to an equal share of those jobs. […] If involuntary unemployment is high, the corresponding basic income will be high. If all unemployment is voluntary, no additional basic income is justified by this procedure.”7

As another way of understanding this point, van Parijs suggests that we think of jobs as resources in themselves (though Piachaud does not seem to entertain this line of reasoning). Perhaps the classic way of thinking of a job is as labour one expends in exchange for resources (a wage). Yet we know that jobs are much more than that – many jobs have value beyond the wage earned, whether in terms of meaning, enjoyment, community, status, etc. This is part of the reason why one might not value the increase in leisure time afforded by unemployment: even where conditional unemployment benefits are generous, most people still prefer work. Since available employment is limited due to the market inefficiencies outlined above, the surfers are doing the aspiring workers a favour, correctly assigning themselves to the ranks of the unemployed so that more jobs are available for those who want them.

If we return, then, to the idea of justice as not imposing costs on others, we can see that the surfers are in the clear. The lowest level of basic income simply corresponds to each individual’s rightful share of the world’s natural resources. Then, where there are additional resources to be redistributed due to the existence in a labour market of employment rents, this is to compensate for the costs imposed on the unemployed by the employed in taking up scarce jobs. There is no distinction between the voluntarily and involuntarily unemployed in entitlement to this level of the basic income – each equally provides a benefit to the employed by freeing up their share of jobs and the various non-monetary benefits that go with them. Directly anticipating and defusing Piachaud’s claim that such rents should only be redistributed to the involuntarily unemployed, van Parijs warns:

“adopting a policy that focuses on the involuntarily unemployed amounts to awarding a privilege to people with an expensive taste for a scarce resource. Those who, for whatever reason (whether to look after an elderly relative or to get engrossed in action painting), give up their share of that resource and thereby leave more of it for others should not therefore be deprived of a fair share of the value of the resource. What holds for scarce land holds just as much for scarce jobs.”8

Arguments about distributive justice like these, that drill down to the fundamentals of the way our economies and societies work, are necessarily abstract. It’s therefore important to be wary of directly inferring real-world policy from such idealised thought experiments. Nevertheless, amidst the complexity of our modern interlocking economic systems, the core argument – that everyone is entitled to their share of the world’s natural resources – is a guiding light.

Reviewed by Tyler Prochazka and Kate McFarland

Read More:

David Piachaud, “Citizen’s Income: Rights and Wrongs,” Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, LSE, November, 2016.

Hilde Latour, “UNITED KINGDOM: David Piachaud Calls Basic Income a Wasteful Distraction from Other Methods of Tackling Poverty,” Basic Income News, February 9, 2017.

Philippe van Parijs, “Why Surfers Should be Fed: The Liberal Case for an Unconditional Basic Income,” Philosophy and Public Affairs, 1991.

John Rawls, “A Theory of Justice,” Harvard University Press, 1971.

John Rawls, “The Priority of the Right and Ideas of the Good,” Philosophy and Public Affairs, 1988.

Ronald Dworkin, “What is Equality? Part 1: Equality of Welfare,” Philosophy and Public Affairs, 1981.

Ronald Dworkin, “What is Equality? Part 2: Equality of Resources,” Philosophy and Public Affairs, 1981.

Ronald Dworkin, “Sovereign Virtue Revisited,” Ethics, 2002.

Main Photo: The photographer reading John Rawls’ ‘A Theory of Justice’, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Dana Hilliot

1. A parallel argument, unexplored here, would address the important question of whether employment is voluntary or involuntary. Under most of today’s welfare systems for able-bodied adults, conditionality and sanctions are used to “incentivise” recipients to take up any job available. This threat of destitution has moral implications, in that it calls into question the consensuality of such employment.

2. John Rawls, “The Priority of the Right and Ideas of the Good,” Philosophy & Public Affairs (1988) p. 257

3. At present, incomes generated from natural resources are directly distributed to citizens in only a handful of cases (the Alaska Permanent Fund and Norway oil fund spring to mind). More commonly, states channel incomes from natural resources into the general budget, or such natural resources pass into the realm of private property. While arguments can be had regarding direct versus indirect distribution – whether each citizen gets their share of the windfall directly, or instead indirectly through government spending – that all citizens should benefit in some way seems uncontroversial.

4. Philippe van Parijs, “Why Surfers Should be Fed: The Liberal Case for an Unconditional Basic Income,” Philosophy and Public Affairs (1991), p117

5. For a quick run-down of the problems with equality of welfare, see this summary from the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy.

6. Ronald Dworkin, “Sovereign Virtue Revisited,” Ethics 113.1 (2002), p111

7. Philippe van Parijs, “Why Surfers Should be Fed: The Liberal Case for an Unconditional Basic Income,” Philosophy and Public Affairs (1991), p124

8. Philippe van Parijs, “Why Surfers Should be Fed: The Liberal Case for an Unconditional Basic Income,” Philosophy and Public Affairs (1991), p126

by Guest Contributor | May 11, 2017 | Opinion

Written by: Conrad Shaw, Bootstraps Documentarian

The Debate

About a month and a half ago, on March 22, the podcast debate forum Intelligence Squared (IQ2) held a debate regarding universal basic income (UBI) in New York City. Being a denizen of New York and a relatively recent and enthusiastic recruit to the cause of UBI advocacy (my partner Deia and I are undertaking an ambitious film project about it), I was eager to go and see this debate play out. I was even more excited when I found out that a recent interviewee and new friend of ours, labor legend Andy Stern, former head of the SEIU union, was to be one of the debaters. This was a chance for a large audience to be presented with the idea of UBI in a thoughtful and cogent way. Andy would be teaming up with libertarian Charles Murray to defend the motion that “Universal Basic Income is the Safety Net of the Future.” Their opponents were to be Jason Furman and Jared Bernstein, Barack Obama’s and Joe Biden’s top economic advisors, respectively.

The outcome of the debate was far less satisfying than I’d hoped it would be. In short, UBI got spanked. IQ2 judges the winner of a debate to be the side that sways more of the audience in their favor. Before the debate, 35% of the audience were for the motion, 20% against, and 45% undecided. Afterward, the numbers were 31% for, 61% against, and 8% undecided. This means that not only did UBI fail to convince any of the undecideds, but some of those who were for it switched sides. As someone who’s putting a lot of effort into making the case for UBI to the American people, this felt like a foreboding omen of what could come as the UBI discussion begins to take the national stage. For something I considered to be so obvious and beneficial, so necessary, to be, instead, so handily quashed was confusing and painful. In order to understand the reaction of the audience, we did some of our own polling of the audience before and after, and I’ll go into why I think the results turned out the way they did below.

I’d had some uneasiness going in, of course. For one, Charles Murray is a persona non grata among many UBI advocates (and others) for attitudes he’s expressed in the past toward disadvantaged populations, suggesting in his book The Bell Curve that intelligence is the primary factor in predicting societal outcomes like pregnancy out of wedlock and crime. That line of thinking, seemingly discounting outright the imbalances many perceive in our society, makes me very uncomfortable. Sure, intelligence factors in, but I also think it foolish to ignore the factors of class, race, and gender, as well as the neighborhood one grows up in. I’ll admit that my information about Mr. Murray was mostly hearsay with a bit of Wikipedia research on my part, so I didn’t truly know what to expect. To some UBI advocates, Murray is the devil, not to be given a platform from which to spout his evil message, and so, quite understandably, I was worried that the debate could be taken down unproductive and perhaps even bigoted paths.

Despite this caricature of Charles, however, he proved to be a shrewd advocate of basic income in the debate. Although he is libertarian, he stuck to lines of argument that did not put off the debate’s mostly liberal Manhattan audience. In the end, he made some lovely appeals to human decency and equality and got a warm reception from the audience. At one point, he even defiantly rejected Mr. Bernstein’s scoffs that he was naive to think people in neighborhoods and communities would be more helpful to each other under a system of security provided by a basic income. It was not lost on me that this “villain” was the one in the room most loudly protesting for the existence and prevalence of basic human decency and of our ability to trust in other human beings, when people are given the chance to be secure.

So Charles wasn’t the issue on that day.

Andy’s arguments were sound and compelling as always, taken in and of themselves. He has an empathetic and adaptive approach, and I’ve become a deep admirer of his ability to think outside the box in a changing world, even when it threatens to overwrite his legacy. In his book, Raising the Floor, co-written with Lee Kravitz, he makes a compelling case as to why labor unions are no longer a tool that will suffice to fight the labor market inequality and disruption many expect moving into the future, even though his most lauded achievements to date are tied to his labor union efforts. It takes a very strong and humble individual to take a pronounced lateral step from his life’s work like that when being confronted with uncomfortable evidence that it has become insufficient.

However, while Andy’s and Charles’s arguments were valid and compelling, they simply were not enough in the context of this debate. They weren’t sufficient to persuade the audience in the face of the arguments and the pedigrees of their opponents. Over and over again, Jason or Jared would dismiss the concept as utopian or idyllic. “$12,000 is great! Why not $25,000, or $50,000, or a million?” is a paraphrase of something Mr. Furman said once or twice that struck me as especially disingenuous.

For the most part, though, the opponents provided honest, albeit predictable, complaints regarding the costs and logistics of distributing UBI, and asserted that it was simply too expensive, that it would amount to taking from the middle class to pay the poor, and that some lower-class people (especially those with children) would lose out under the UBI scheme Andy proposed. Disagreeing with much of this assessment, I awaited the response that would put those claims to rest in the minds of the audience, but they didn’t come. Andy and Charles chose to pursue more ideological arguments than economical and logistical ones, and the audience roundly took that to mean that the math really wasn’t there.

Our conversations with audience members after the event made clear to us that this was the issue that swayed them. They came in hopeful, and many were leaning toward this strange concept of UBI, and then the chief economic advisors of their political heroes and most powerful men in the world walked out and dismissed it as numerically, arithmetically infeasible, and that claim was not rebutted. If you watched the debate, you may have noticed a rather dashing yet awkward young man in a checkered shirt, trying not to appear unhinged while asking the second audience question (at 1:01:23), in an effort to steer the discussion toward specific and practical ways that could be implemented to pay for a real, workable, UBI. That slightly agitated fellow was me, and my question wasn’t really answered at the time, except with the outright assurance by the opponents that my suggestions simply would not be enough.

I felt a little nauseated during the final tallying phase, because I sensed the spanking coming. These people needed to hear that this is not just an idealistic plan, but an intelligent plan, and the details weren’t provided for them to believe in that.

In the end, I thought all of the debaters did a fine job presenting their arguments. Andy and Charles hit the old beautiful points on human rights, human nature, and the promise of a world of security that I had hoped they would, and they also sounded the alarm bells about the impending threat of automation to our workforce. Jason and Jared displayed a wealth of experience as well as real compassion for those in need in our society. I sensed a lot of room for common ground. I felt that the real issues that might remain, if the money issue could be resolved, would be 1) a disagreement around how to administer aid in general, in essence whether people could be trusted with cash and freedom over bureaucratic in-kind giving, and 2) the dilemma of political feasibility, whether in working up the will of the people or that of the Congress.

I also thought the debate format was one of the best I’ve seen, with incredibly delicate and intelligent moderation executed by John Donvan, who struck me as funny, nimble, and fair. Deia and I were truly honored to be there and thrilled that UBI was getting real time in the national dialogue.

The format, however, still left one major thing to be desired for me. It was still a debate. Debates are made for winning, and throughout this one you can hear both sides often plea “and that’s why I want you to vote for my side.” I much prefer a discussion to a debate, with no declared winners or losers. If the only thing to be gained is a bit of mutual growth and understanding, I think we can all get to the work of progressing a little faster.

Actively keeping my cool after the final applause, I hovered maybe 12 feet from Jason Furman and his friends and admirers until I could politely poke my head in and beg him for an interview. I already had about 453 questions in mind. He graciously accepted without a second thought, which went a long way in elevating my estimation of a man who had just stepped on my heart and ground it into the dirt a little.

The Interview

A few weeks later, Deia and I were on a bus from New York City to Washington D.C. to interview not only our first opponent of UBI, but a man who had batted it down so very effectively and seemingly effortlessly. I was nervous, thinking about how new at interviewing I am. Was this going to be a gotcha interview? Should I try to catch him with his words somehow? As I doubted whether I could pull that off, even if I wanted to, in the end I decided that I really just wanted to tap into his very real working expertise of the American economy. This man is an extremely valuable resource, a wealth of knowledge, it occurred to me. Come to think of it, as a chief advisor of one of my greatest heroes (yes, I love me some Obama), and someone who was instrumental (along with Andy Stern, I might add) in passing some very consequential legislation, I reminded myself that Jason Furman, then, is also a hero of mine. He even shared a freshman dorm room with Matt Damon, another major role model in my acting and filmmaking pursuits. Oh crap. Was I going to geek out and ask awful fanboy questions about all his friends or about his D.C. battle stories? Would I be that kind of interviewer?

But enough of my inner monologue. We’re here to talk about UBI, about the economy, about a nation’s growing pains and long-established shortcomings, and about truly progressive solutions to bring greater empowerment, dignity, and democracy into the lives of over 300 million people.

Still, a large part of me expected to walk out of our interview frustrated once again.

In his very first comment, Mr. Furman expressed regret that he hadn’t emphasized during the debate that he is very much open to discussing the merits of direct cash benefits as opposed to in-kind ones, and that his main criticism of UBI was, in fact, the universality of it. This was immediately a change in tone indeed, and it set me at much greater ease about the plan I had made for my line of questions:

1) I would start from a premise, a proposed national implementation scheme for UBI taken as sort of a “best of” from the many versions Deia and I have come across in our interviews, plus a few tweaks of my own, and would establish that all questions in this interview should be considered in the context of this proposed system rather than any other conceptions of UBI floating about.

2) I would walk Mr. Furman, one item at a time, through a list of potential sources of revenue that I was aware of and ask him, in his experienced opinion, what each of those sources could bring in.

Simple.

The “wonkiest of wonks,” as Mr. Furman has been called, was happy to oblige this approach. He would make no promises, and these were all to be understood as ballpark estimations, but he would give his best effort.

The Premise

Although my ideas have evolved slightly since publishing an article that included a nascent version of them, a little while back, my proposal for implementation still generally holds the same. This is a simplified version of it. None of these ideas are groundbreaking within the basic income movement, and many others would likely venture forth a very similar scheme:

- $12,000 per year per adult, delivered at least monthly (preferably weekly) via direct deposit to individual accounts (not as cumulative sums to joint or family accounts)

- $4,000 per child, paid to each child’s guardian, until 18 or age of emancipation, whichever comes first, with a percentage (I suggested 25%) being kept in a trust for the child to access at emancipation, when they would also begin to receive the full $12,000. (Note: It has since been argued to me that all of a child’s money in a UBI program should be accessible to the guardian as needed, and any baby bond type program would be better kept as a separate program, and I’m open to that as well.)

- Current welfare programs should not be directly axed so much as allowed to naturally phase into obsolescence. For example, if every American’s basic income were high enough to disqualify them for food stamps, then food stamps would naturally disappear, and the food stamp bureaucracy along with it. This would follow the basic rule of “do no harm,” in that the benefits an individual received under a UBI must be at least as valuable as welfare benefits previously received, and so at the very least nobody would be worse off financially, and now the aid would be guaranteed and permanent instead of something for which one must perpetually qualify, and instead of something that would be lost upon earning more income elsewhere.

- The total cost of this plan, given the current population and demographics of the U.S., would be approximately $3.3 trillion.

This plan immediately differed in a couple major ways from the plan Mr. Furman argued against at the IQ2 Debate, the plan Andy and Charles were using as their premise. Most notably, Andy’s plan did not provide any basic income for children. This was Furman’s primary complaint against that plan, in fact, because it would in essence act more beneficially toward singles or those without children than toward families. A family of five would fare worse than a family of four, all other things being equal. Furman stated to me outright that this one change made him much more amenable to the plan I proposed.

The major remaining issue now was the same issue I imagine Andy was hoping to mitigate by leaving children out of his plan: the price. Andy’s plan was $1.8 trillion to my $3.3 trillion, and if Furman painted Andy’s cost as naive and fundamentally unfeasible, mine must be delusional. But he was willing to go through the numbers, and I felt good that he was now at least in support, morally, of the structure of the benefits and the effect they would have on the American people.

So how, then, do we pay for it?

Let’s start simple. Funded with the most blunt instrument possible, this $3.3 trillion price tag would require levying approximately a 20-25% flat tax (depending on how you choose to approximate it) on top of our current progressive system. In other words, every American would pay an additional 20-25% on whatever income they earn outside of the basic income. In a worse-case scenario of a 25% flat tax, this would create a break-even point of $48,000 for an individual. Citizens earning less than this break-even point would be net beneficiaries of the system (in essence, the individual earning $48,000 would pay an extra $12,000 in taxes and receive $12,000 in basic income). The break-even point for a family of four would be $128,000. The less you make, the more of your basic income you end up keeping.

Of course, this means that people above the break-even point would be net contributors, paying more into the program than receiving from it, and most would agree that levying even a small amount of extra taxes on someone making $50K-$60K is neither ideal nor easy to sell politically. Even though it would already represent a net benefit for more than 60% of the country, and even if it would essentially eradicate extreme poverty and homelessness, and even if it would give every American enough security to know they won’t ever end up in the streets, we should be able to do better than $48,000, right?

And so if we want to do this intelligently, we shouldn’t simply slap a flat tax on top of the system we already have and call it a day. We should pay for as much of the UBI as possible through other means in order to drag the necessary flat tax percentage down. If we can lower it to 15%, for example, then the break-even point for individuals would become $80,000. At 10%, it would be $120,000. For families of four, it would be $213,000 and $320,000, respectively. At that point you’d have to be in the top 10%-20% of the country to not be receiving extra money off of UBI. So, let’s try to work in that direction.

Does all of this still sound numerically far-fetched? How could 90% of the country directly profit off of a system like this? The money has to come from somewhere, right? Does this amount to pure socialism? I had the very same instincts at first, and so some back-of-the-napkin calculations were necessary for me to even decide whether UBI was idle fantasy or worth looking into further.

The reality truly is numerically far-fetched in the opposite direction, and it’s just not yet widely understood the extent to which that is the case. The extremely wealthy make so much more money than the rest of Americans that funding a UBI is more than feasible. Just as an example, if we went full socialist and we took all of the net worth and income that households in this country own and make, that we know of, and divided it evenly between all Americans, we could give every man, woman, and child each around $280,000 in savings and an income of $55,000 per year.

Think about that for a minute, or twelve. That includes children, the homeless, and retirees. That would be over a million in the bank and a yearly income of $220,000 for every family of four. That’s how rich the rich are. That’s what has been hidden from us. If we’re asking for zero redistribution of already-owned wealth and only $12,000 of that $55,000 in income per person per year so that nobody starves in the street, it’s not only possible, but it’s simple. It’s a matter of public awareness and political will. It’s a matter of priorities and values. Homelessness and poverty are choices made not by their victims, but by the very structure of our society. Every time we feel a pang of guilt at walking by a homeless person on the street, it should be accompanied by a stab of outrage, because we have the power, today, to fix it. If we don’t each stand up and fight for it, we are each complicit in the pain of so many.

Also, bear in mind that UBI won’t solve the problem of massive income inequality. The very wealthy will remain the very wealthy. Poverty will still be a force to be reckoned with as automation disrupts labor markets. Further changes to our system will undoubtedly be needed. But a UBI can ensure that nobody need be on the street, and that everyone can live in dignity while we wade through the transformational societal changes on our horizon. Many will still struggle, but no one will have zero. It won’t guarantee anyone luxury, but everyone will have options.

The Devil in the Details

With the bigger picture numbers laid out, we then must delve into the finer points of financing a basic income. Here is where Mr. Furman and all of his up close and personal experience re-enter the picture.

You can listen to the interview and/or read the transcript to see for yourself what we came up with and how it unfolded. These numbers, I’ll note, are very rough estimates, and they seem to me to trend in a more conservative direction. In many cases Furman was not comfortable venturing a guess at all, and so I left those out. Here’s a summary of his estimates in trillions:

In essence, even with many potential forms of revenue discounted (including the ones I forgot to bring up, like a VAT tax, a wealth tax, etc.); with arguably conservative estimates given all around; with zero accounting for potential positive benefits in areas of stimulus, crime reduction, health improvement, etc.; and with only a 10% flat tax added, we came up with ⅔ of the $3.3 trillion needed for my proposed plan. That would be enough for on the order of $7,000 per adult and $2,700 per child each year. This, to me, represents an amount I would be ecstatic to see in any legislation coming up, an amount that would deal a tremendous blow to poverty in America and act as a significant empowering agent for Americans.

Again, many will point out that these numbers are all very fuzzy. Of course they are. The intent here is to show that the scale of the funding is feasible. If you disagree with the values, then let’s sit down and hash out what they truly should be and see what total we arrive at.

No doubt Furman saw where I was going with this line of inquiry, and in the end I imagine that’s why he affirmed that he’d rather see that same money going toward a childless EITC or other, more targeted forms of getting cash to people. This implies to me that, in the end, the financial feasibility of a UBI is not the real issue for him. At the heart of his hesitance is valid concern over the method of delivery of aid, and at the heart of that delivery system lies an issue of faith. Who do we trust more with money, our government or our people, and to what extent? I daresay that nobody wants the government having a hand in all of our day to day decisions, and yet most of us will recognize the need for a certain amount of regulation and oversight to protect us from the large and insensitive forces of capitalism to which we are vulnerable as small individuals. Furman apparently leans more in the direction of relying on government to determine how money should be spent. Those in favor of UBI put more of their trust in individuals. Both parties seem to me to lie not too far from each other on the spectrum, just on opposite sides of center. Then there are those who are far more extreme in either direction.

I certainly can’t blame Furman for his inclinations. We’re talking about his legacy, after all, and the liberal government has arguably managed to affect measurable, positive change, raising many out of poverty who would be there without any bureaucratic aid. It will take great strength of character for our country and our civil servants to see where we need something drastically new and better than our tried methods, and, as Andy Stern did when he stepped away from the SEIU labor union, to bravely and humbly take that lateral step away from our legacies. We must abandon the hope that a benevolent bureaucracy will save us from our ills and instead invest in deputizing our people to enhance their own well-being and create more opportunities for themselves. Our social safety net has served to arrest our fall in many ways, and so it has been beneficial, but people are falling through the holes of that net, and some people have missed it entirely. It’s time to retire the net and replace it with a floor. As a people, we can stand on a floor. We can walk on a floor. We can build upon a floor. Have you ever tried building on a net?

UBI is about putting the money in the hands of the citizens to choose for themselves how to spend it best. It’s about removing the middle-man, the father figure, and the teacher, instead trusting individuals and communities to step up to the plate and invest in themselves in the wisest ways they can. Basic income is, quite simply, power to the people boiled down to its most simple essence: cash. And cash is nothing more than our expression of security.

If we can drive the conversation beyond semantics and distractions to these very fundamental principles, and if we can carry out this discussion civilly and with respect for all political leanings and backgrounds, I believe that implementing a universal basic income will emerge as an irrefutably sensible solution moving forward, passed by wide, nonpartisan popular support. What I encountered most in our interview with Mr. Furman was agreement, and we have had much the same experience with every American we engage in this discussion, be they liberal, conservative, libertarian, progressive, or other. Almost everyone, pro or anti, Furman included, expresses great interest in seeing the results of the ongoing basic income trials going on all over the world. This gives me great hope.

(Note: Speaking of basic income trials, we’re doing one of our own for our documentary BOOTSTRAPS. Our aim is to share with the public the human stories of real Americans from all walks of life receiving a basic income for two years. If you count yourself among the many who are either supporters of UBI or who are unsure about it but would be very interested to see the results, please consider contributing to our crowdfunding campaign. Every dollar will go toward our pilot, meaning into the bank accounts of the subjects of our film. Our production budget will be raised and administered separately. If you’re interested in being involved with or helping the production, you can contribute to the production fund or write to us at bootstrapsfilm@gmail.com.)

Image from iq2 UBI debate website.

by Kate McFarland | May 10, 2017 | News

On Tuesday, May 9, an article published in The Independent alleged that Finland’s Basic Income Experiment has already produced evidence that unconditional payments lower stress and improve mental health for unemployed Finns.

This widely shared article generated rumors that the Finnish government has released the first results of this two-year pilot study, which commenced on January 1, including the above findings. These rumors are inaccurate, and the present post aims to address this misconstrual.

Background on Finland’s Basic Income Experiment

Directed by Kela, the Social Insurance Institution of Finland, Finland’s nationwide pilot study of basic income generated widespread international interest from its announcement in 2015 to its launch at the start of 2017. In its current design, the experiment is restricted to those between ages 25 and 58 who were receiving unemployment assistance at the end of 2016. Nonetheless, it differs from several other contemporary so-called “basic income experiments” in that the experimental group–consisting of 2,000 randomly selected individuals from the above target group–receives cash payments (€560 per month) that are indeed unconditional, individual, and not means tested (compare, for example, to the experiments planned or underway in Ontario, the Netherlands, Barcelona, and Livorno, Italy).

Many basic income supporters and followers are, no doubt, eagerly anticipating the results of this experiment, which will continue through December 31, 2018. Here, though, it is important to keep in mind several caveats–especially as rumors of initial results begin to surface.

1. Kela will publish no results prior to the end of the experiment (i.e. December 31, 2018).

In a blog post published in January, in response to the widespread media attention directed at the experiment, research team leader Olli Kangas and three colleagues explain that publishing any results during the course of the experiment runs the risk of influencing participants’ behavior:

A final evaluation of the effects of the basic income can only be made after a sufficiently long period of time has elapsed for the effects to become apparent. The two-year run of the experiment is not very long for changes in behaviour to materialise. The potential of the experiment, short as it is, to provide reliable results should not be undermined by reporting its effects while it is underway.

2. Kela will conduct no questionnaires or interviews of participants while the experiment is in progress.

As the same blog states, the researchers will minimize their reliance on questionnaires and interviews to gain information about study participants–again to minimize the effect of observation on behavior–relying instead on data available from administrative registries. If any individual questionnaires or interviews are used, they “will not be conducted without careful consideration, and not before the experiment has ended.”

3. Analysis of the experiment will focus on labor market effects.

A major reason for the Finnish government’s interest in basic income has been the policy’s potential to improve employment incentives (in contrast to Finland’s current unemployment benefits, which are reduced by 50% of earned income if a recipient takes a part-time job and which demand much bureaucratic oversight of individuals). Correspondingly, a main objective of the experiment, as stated by Kela, is to determine “whether there are differences in employment rates between those receiving and those not receiving a basic income.”

Some basic income proponents have criticized the Finnish pilot for its lack of attention to other potential beneficial effects of basic income, such as its effects on individual health and well-being; however, Kela has no current plans to examine such effects.

“Reduced Stress” Claim

It is in this context that we must read The Independent’s recent article “Finland’s universal basic income trial for unemployed reduces stress levels, says official.”

As its data, the article quotes Kela official Marjukka Turunen (Head of Legal Affairs Unit) as saying, “There was this one woman who said: ‘I was afraid every time the phone would ring, that unemployment services are calling to offer me a job’,” and, “This experiment really has an indirect impact, also, on the stress levels [of people] and the mental health and so on.”

These quotes originate in a recent interview on WNYC’s podcast The Takeaway, in an episode on automation and the future of work, in which host John Hockenberry interviewed Turunen about Finland’s basic income experiment, having presented basic income as a possible policy response to technological unemployment. After stressing the potential of basic income to promote employment (by avoiding the welfare trap and reducing bureaucracy and paperwork), Turunen related the anecdote above in reply to a question in which Hockenberry turned about the effects of basic income on feelings of confidence and self-respect.

In comments to Basic Income News, Turunen explained that this situation involved a participant who agreed to participate in a media interview and volunteered this information to the reporter. While some participants themselves offer feedback to Kela, Kela itself is not allowed to divulge this information to the media, nor to provide any personal information about the study participants. However, this does not prevent participants themselves from volunteering to talk about the experiment to media, as in the present situation.

Thus, it is important not to mistake this unsolicited feedback from experiment participants for official and formal results–which are still more than a year and half away. As Turunen comments,

We do not have any results yet, not until the end of next year; these insights are coming from the customers themselves willing to talk about this in the media. And these are only insights, the results must be very carefully analyzed according to the information we only get at the end of next year.

More Information:

Kela, Basic Income Experiment 2017–2018. (Official website on the experiment.)

Olli Kangas, et al, “Public attention directed at the individuals participating in the basic income experiment may undermine the reliability of results,” Kela blog, January 16, 2017.

“The Shift: Exploring America’s Rapidly Changing Workforce,” The Takeaway (podcast), May 4, 2017. (Marjukka Turunen’s remarks in context.)

Reviewed by Russell Ingram

Photo (Helsinki) CC BY-NC 2.0 Mariano Mantel

by Wolfgang Müller | May 10, 2017 | News

In his piece “Universal Basic Income – could it work?”, Gwynne Dyer writes that current populism fails to realize the extent of automation. Promises like “bring the jobs back” and a full-employment economy ignore the extent of automation in technology. Automation of work is expected to increase over the next twenty years and the author believes this change will negatively influence democratic processes and economic structures. As such, the author believes the latter causes the right wing to think about UBI as a way to provide a potential solution to current problems in economic models. However, it is unclear how the author connects these events.

The author questions: why give funds unconditionally, from where does the money come, and would people still work? These questions are important for each political party to evaluate. In addition, the author cites pilot studies in Canada, the Netherlands, and Finland that aim to develop evidence and understanding of UBI impacts. He believes the results of studies will be useful to developing the conversation around UBI.

More information at:

Gwynne Dyer, “Universal Basic Income – could it work?“, The Telegram, February 18th 2017.

by Kate McFarland | May 9, 2017 | News

Researchers in several Dutch municipalities are preparing experiments to test the effects of the removal of conditions on social assistance. Although not testing basic income per se, the experiments will examine one of its key attributes (the reduction of conditionality).

This year, popular sources have occasionally continued to report that the Dutch city of Utrecht is preparing to launch–or has already launched–a pilot study of universal basic income (sometimes continuing to cite a now-outdated article published in The Atlantic in June 2016). In this light, it is particularly important to clarify the facts surrounding the Dutch social assistance experiments.

It is true that researchers have proposed experiments in several Dutch municipalities that will examine the effects of reducing conditions on welfare benefits, including the removal of job-seeking requirements and a lessening in the amount benefits are reduced with income. However, as explained below, these experiments will not test a full-fledged basic income. Moreover, at the time of this writing, none of the municipal social experiments have been launched: those in Groningen, Tilburg, and Wageningen are awaiting approval from the Dutch Ministry of Social Affairs; meanwhile, the experiment in Utrecht has been delayed indefinitely, having been denied approval by the Ministry.

Background: The Participation Act, Motivation, and Design

The Dutch Participation Act, enacted in 2015, imposes conditions on recipients of social welfare that are intended to promote their reintegration into paid employment. For example, beneficiaries are typically required to complete five job applications per week, attend group meetings, and participate in training activities in order to continue receive cash assistance.

Researchers at Utrecht University School of Economics, such as Loek Groot and Timo Verlaat, have criticized the conditions and sanctions imposed by the Participation Act from standpoint of behavioral economics. Research in behavioral economics has demonstrated, for example, that performing tasks for monetary rewards can “crowd out” individuals’ intrinsic motivation to perform such tasks. Furthermore, deprivation and fear of losing benefits may engender a scarcity mindset that impedes rational decision making. Drawing from such findings, researchers like Groot and Verlaat have hypothesized that reducing conditions on welfare benefits would better promote individuals’ reintegration and productive contributions to society (see, e.g., “Utrecht University and City of Utrecht start experiment to study alternative forms of social assistance,” last accessed May 6, 2017; note that the start date mentioned in the article, May 1, is no longer accurate).

The social experiments proposed in Utrecht and other Dutch municipalities have been designed to test the above hypothesis: randomly selected welfare recipients (who agree to participate) will be randomly assigned either to a control group or a treatment group, one in which reintegration requirements on receipt of benefits will be removed. (Although the exact design of the experiments has differed between municipalities–and between versions of the proposal–all have included a treatment group with the elimination of job-seeking conditions. Proposals experiments have also included groups with different interventions, such as, in several recent versions, increased reintegration requirements and relaxation on means-testing; see below.) These treatment groups will be compared to a control group, as well as a reference group composed of individuals not selected for the experiment, with respect to outcomes such as labor market participation, debt, health, and life-satisfaction.

Meanwhile, however, researchers must grapple with another consequence of the Participation Act: the law limits the extent to which they are legally permitted to test alternative welfare policies. For one, as mentioned in a previous Basic Income News article, the Ministry of Social Affairs has required that the municipal officials overseeing the experiment must check after six and twelve months to determine whether experimental subjects have made sufficient efforts to find paid work. At these times, if an individual has been found to have undertaken too few employment-promoting activities, their participation in the experiment must be ended. This constraint reintroduces some degree of conditionality even for treatment groups in which the requirement to participate in reintegration activities has been lifted from social assistance.

In addition, the Ministry has also requested that experiments include an additional treatment group in which stricter reintegration requirements are introduced. The experiments proposed for the municipalities of Tilburg, Wageningen, and Groningen, are currently under review by the Ministry, include such a treatment group; the initial (and unapproval) design of the Utrecht experiment did not.

Relationship to Basic Income

Largely for political reasons, proponents of the Dutch social experiments have avoided the use of the term ‘basic income’ (‘basisinkomen’ in Dutch), with researchers in Utrecht calling their proposed experiment by the name ‘Weten Wat Werkt’ (English: ‘Know What Works’). (In the Netherlands, “basic income” is often associated with the stereotype of “giving free money to lazy people”.)

This avoidance is apt, however, since the experiments have indeed not been designed to test a universal and fully unconditional basic income. The designs of the experiments have either not been finalized or are still pending government approval (see below). Regardless, however, it seems certain that any of the experiments (if approved) will test policies that differ from a basic income in several key respects. First, the population of the experiment is not “universal”; participants are to be selected from current welfare recipients (as is also the case in Finland’s Basic Income Experiment, launched on January 1, 2017, which has also been designed to test the labor market effects of the removal of conditions on welfare benefits for the unemployed).

Furthermore, within the treatment conditions themselves, the benefit will remain means-tested and household-based (rather than individual-based), in both respects unlike a basic income. In all designs proposed to date, participants within all treatment groups will have their benefits reduced if they take a paid job during the course of the experiment. However, the Tilburg, Wageningen, and Groningen experiments, as currently planned, will include a treatment group in which benefits would be reduced at slower rate (50% of earned income instead of 75%).

In the latter respects, the Dutch municipal experiments bear more similarity to the Ontario Basic Income Pilot than Finland’s Basic Income Experiment [1]. While the Finnish pilot is indeed investigating non-means-tested benefits paid to individuals, the pilot studies in Ontario and (if approved) the Netherlands will continue to work with programs in which the amount of benefits depend on income and household status; however, in all cases, many conditionalities on benefits will be removed in some experimental conditions.

Despite these differences, some view the Dutch social assistance experiments as a possible step toward a full-fledged basic income. Moreover, as seen above, the experiments have been motivated largely by arguments from behavioral economics that have previously been invoked in arguments in favor of the unconditionality of basic income (see, e.g., the 2009 Basic Income Studies article “Behavioral Economics and The Basic Income Guarantee” by Wesley J. Pech).

Status of the Experiments

In contrast to some rumors and media presentations, none of the proposed social assistance experiments in the Netherlands has yet been launched.

The experiment in Utrecht, which had earlier in the year been to declared to have a launch date of May 1, has been deferred. According to a statement about the experiment on the City of Utrecht webpage, “The Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment has indicated that we need to do the experiment in a different way. We are discussing how we can conduct the study.”

Researchers are currently considering alternative designs of the experiment that will bring them into compliance with the Participation Act, and no new start date has been announced.

Meanwhile, the Ministry is reviewing experiments proposed in Tilburg, Wageningen, and Groningen, with an announcement expected later in May. As previously mentioned, these experiments have been designed to avoid conflict with the Participation Act, as had been one concern with the originally proposed design of the Utrecht experiment.

Basic Income News will publish a follow-up article of the Dutch municipal experiments, including further details on their design and implementation, after their final approval by the government.

Thanks to Arjen Edzes, Ruud Muffels, and Timo Verlaat for information and updates, and to Florie Barnhoorn and Dave Clegg for reviewing this article.

Photo: Groningen, CC BY 2.0 Bert Kaufmann

[1] I am here using these terms as proper names given by the respective governments, despite the differences between the experimental programs and a basic income as defined by BIEN.