by BIEN | Aug 22, 2017 | News

Futurism reported on automation, robots, and universal basic income through the provision of a chart-article. Some of the information summarized by the chart includes that fact that as there are 4.73 robots working per 100 human workers in South Korea. The global average is 0.66 per 100 workers. That ratio is reported to be rising rapidly throughout the world. Also, with more robots, they become cheaper to implement. Workers in the developing world are most at risk of losing jobs due to automation.

The problem is not limited manufacturing, however. It includes diverse areas such as farm labor, construction labor, truck drivers, mailer carriers, and so on. The chart mentions that $2,600 per month as a UBI solution is being considered in Switzerland, which BIEN has reported on, and only $1,000 per year in Kenya.(same paragraph as above) The chart also describes the cases of Alaska, Namibia, and Harper Lee.

It ends with quotes from supporters of a UBI, including Martin Luther King, Jr., Bertrand Russell, Harris Levine, Jeremy Howard, F.A. Hayek, and Thomas Paine.

More information at:

Futurism, “Universal Basic Income: The Answer to Automation?“, Futurism, June 2017

by Claire Bott | Aug 18, 2017 | News

Richard Branson. Credit to: Wikipedia.

Multi-billionaire Richard Branson, founder of Virgin, recently became the latest wealthy entrepreneur to publicly support universal basic income (UBI), following similar public statements by Mark Zuckerberg, the co-founder of Facebook and Stewart Butterfield, the co-founder of Flickr.

Writing on his personal blog on the Virgin website, Branson said: “In the modern world, everybody should have the opportunity to work and to thrive. Most countries can afford to make sure that everybody has their basic needs covered. One idea that could help make this a reality is a universal basic income. This concept should be further explored to see how it can work practically.”

He went on to discuss the UBI experiments currently taking place in Finland, and stated that: “A key point is that the money will be paid even if the people find work. The initiative aims to reduce unemployment and poverty while cutting red tape, allowing people to pursue the dignity and purpose of work without the fear of losing their benefits by taking a low-paid job.”

Branson also indicated that he had discussed this with The Elders, a group he helped to create which aims to be the “village elders” of the new “global village”. The Elders include members such as Desmond Tutu, Nelson Mandela, Jimmy Carter, Kofi Annan and Ban Ki-Moon. He reported: “What I took away from the talks was the sense of self-esteem that universal basic income could provide to people.”

More information at:

Richard Branson, “Experimenting with Universal Basic Income”, Richard Branson’s blog, 14th August 2017

Edited by Genevieve Shanahan

by Guest Contributor | Aug 18, 2017 | Opinion

According to the OECD, basic income (BI) is not an effective tool for reducing poverty. However, the outcome would depend on the model chosen for implementing a BI system, as well as the changes made in other parts of social protection.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) published in May a Policy Brief paper studying the feasibility of a basic income model in four OECD countries, one of which was Finland.

On June 16, Kela organized a seminar in which Herwig Immervoll, a senior economist at the OECD, discussed the findings of his study and analysed the strengths and weaknesses of a BI scheme. After the seminar, the national broadcasting company YLE reported: “Universal basic income might increase poverty and inequality”.

Apart from Finland, the OECD study includes France, Italy and the United Kingdom. The analysis was done with the help of the EUROMOD microsimulation model. In each country, the starting point for the analysis was to take all existing spending on social cash-transfers together and see what level of BI they would amount to. Eventually, the level of BI was set near the existing levels of guaranteed minimum-income benefits for single individuals in each country, adjusted so that it would not increase the public expenditures.

In Finland, this resulted a BI of 527 euros for the working age adults and 316 euros for children and youth under 18 years of age. Those entitled to old-age pensions within the current main statutory retirement age (in Finland over 65-year-olds) were excluded from the BI model.

In the BI model used in the OECD analysis, all existing working-age benefits (including social insurance benefits) apart from cash transfers for housing and disability would be abolished. Also, the zero-rate tax bands of income-tax schedules and equivalent tax-free allowances would be abolished, and all income-tax thresholds would be shifted downwards by a corresponding amount. BI would be made taxable under personal income taxation alongside other taxable incomes.

The OECD model would create many gainers and losers

The most important outcome of the OECD study is that the simulated BI model would strongly impact the income distribution in all studied countries. However, the effects vary greatly among the countries.

In all income groups, the BI model would create many gainers and losers. It would change the net income of most people in one way or another. It would lift some groups out of poverty and thrust others below the poverty line.

The simulated BI model would increase the income level of those small income groups who are currently not receiving any social benefits, or whose benefit level is very low. In turn, those receiving earnings-related benefits or several means-tested benefits would see a decline in their standard of living.

In Finland, those below 65-years-old receiving old-age pensions and single parents with low incomes would be among the losers of the model. The middle-income earners instead would generally benefit from the model.

The conclusion of the OECD is that particularly in countries with a comprehensive social protection BI is not an efficient tool for reducing poverty, since it does not target the benefits effectively. According to the OECD, a budget-neutral BI would not be distributionally neutral. High enough to be socially and politically meaningful and fiscally realistic, a BI would still require tax rises as well as reductions in existing benefits.

A very low basic income, instead, would have little other significance but increase poverty.

The outcomes of BI depend on reforms in taxation and social protection

How the findings of the OECD study are to be interpreted in the Finnish context?

Perhaps the most important issue that the research sheds light on is the fact that there are many institutional challenges in implementing a BI system, and those challenges differ among countries due to their different systems of social security and taxation.

As the OECD report (p. 5) notes, BI as an idea is simple, but the existing social protection systems are not. Therefore, there are grounds to argue that the same model of BI does not fit everywhere. If a reform such as BI were to be carried out, it needs to be adjusted to the existing institutions of social protection and taxation in each country separately. The parameters of the model should be adjusted so that it will not produce excessive changes in people’s incomes.

The greatest problems of the OECD’s microsimulation are that the income taxation is not changed to correspond with the BI model, and that the existing systems are demolished by the same means everywhere without examining the structures of social protection in each country separately. Due to this, BI seems to have unpredictable effects to income distribution.

The income distribution produced by a BI model can be influenced by adjusting the parameters of taxation and social security. In his presentation at the Kela seminar, Herwig Immervoll mentioned that tax reforms should be discussed in parallel with BI. Indirect taxes, such as environmental or value added taxes, have often been proposed as a complementary source for financing a BI scheme, combined with income taxation.

However, the OECD report does not mention these alternatives, and the premise seems to be that taxation in any form should not be increased.

In Finland, as well as in many other countries, some organisations and individuals have launched models of BI adjusted to the local context. Their objective has often (yet not always) been to not radically alter the income distribution or cause reductions in people’s after-tax incomes, especially in the lowest income groups. Microsimulation has been employed at least in the models of partial BI by the Green Party and the Left Alliance, and in the preliminary study for the national BI trial conducted by Kela.

In these models, BI is linked with a reform in income taxation that is designed so that radical changes in after-tax incomes will not occur in any income group. The aim is also to make the models budget neutral, that is, to cover the costs of BI by reforms in taxation and replacing the existing benefit systems. In these models, the old system will be abolished only in those parts where the level of benefits is lower than the BI.

One of the problems with the BI trial currently underway is that due to time constraints, the taxation reform proposed by the research team that designed the experiment was not included.

Will Finland implement a BI?

Though there exist BI models in Finland that would technically allow implementation of a BI system without radical changes in income distribution or public financing, the road of BI will probably be rocky even here.

The preparations of the BI experiment scheme revealed many institutional challenges in implementation of a BI model. The greatest obstacles for a BI are, however, ideological.

In Finland, BI has gained interest especially as a possibility to improve the incentives for paid work. The possibility to combine wages with social benefits more smoothly than today is an issue that no party opposes. Yet, many still find it morally wrong to give people money with no obligations. The opponents of BI fear that the “free money” would reduce people’s willingness to work and give a moral legitimacy to not apply for jobs.

If the only, or at least the most important function of BI is to improve work incentives, the great promises of BI may not be fulfilled after all. The preliminary studies for the BI trial revealed that BI models do not always unambiguously remove incentive traps, if parts of the old social security stay intact.

However, it seems likely that in Finland, as well as in other industrialised countries, the social security will be reformed in a direction that may contain some elements of BI, but not necessarily a ‘pure’ BI model.

If the political thinking emphasizing the labour supply and austerity in public economy prevail, the prospects for more generous BI models seem to be low. In the framework of current economic policies, the implementation of a BI would most probably mean at least demolishing large parts or other forms of social security.

BI as a social dividend?

The OECD report (p. 8) ends up recommending some kind of ’partial’ alternative of a BI model. One option mentioned is a possibility to introduce BI as a separate system from the existing social protection, whose function would be to share the benefits of globalisation and technological progress more equally.

This idea of ‘social dividend’ has often appeared in BI discussions. The state of Alaska is already giving an annual share of the permanent fund based on oil revenues to each citizen as a social dividend. There is similar thinking linked also to the idea of “helicopter money”, originally introduced by Milton Friedman, a cash transfer paid by the central bank to people’s accounts to stimulate consumer demand in economic downturns.

Considering BI as a social dividend would locate it in a new frame, where its function would not be to fix the problems of social security systems, but to distribute purchasing power also to those who lose their jobs or end up in low paid precarious jobs in the labour market turmoil caused by digitalization.

If BI were paid on top of other social benefits, its level could even be lower, or for instance connected to macro economy indicators. In that case, it could also be used to stimulate economies in downturns.

Johanna Perkiö

M.Soc.Sc., Doctoral Candidate

University of Tampere

email: johanna.perkio(at)uta.fi

Original article:

Johanna Perkiö, “The OECD and the problems of basic income“, Kela, June 30, 2017.

by Jason Burke Murphy | Aug 16, 2017 | Opinion

I hardly ever respond to anything in writing if I am not remembering it at least a year or so later. The piece I am remembering is an episode of the podcast Freakonomics called “Is The World Ready for A Guaranteed Basic Income?” I recommend it as an introduction.

I am going to give you a quote and then I want you to keep reading.

Sam Altman runs Y Combinator, a technology venture capitalist firm that has had some great successes and is now interested in funding social science research that will include basic income. Here is the quote, which came up during his interview in this podcast episode:

Maybe 90 percent of people will go smoke pot and play video games. But if 10 percent of the people go create new products and services and new wealth, that’s still a huge net win.

We are back to the couch potato. This character appears in a lot of objections to basic income. Altman concedes that there will be couch potatoes. He just thinks that is a good price to pay to get more entrepreneurs, even only a few of them. I appealed earlier for the reader to keep going because most people in my orbit would not like this quote. (If it sounds good to you, then I guess I should still urge you to keep reading.) I will explain why some will push back and why I ultimately do not.

We are starting to see increased support for as well as new sorts of negative reactions to the idea. Not very long ago, basic income advocates were often introducing the idea to specific audiences. This meant one could get away with starting where you thought the listener would react best. If you were talking to someone on the left, you might call it a “strike fund for all”. If someone is more liberal, you would emphasize that a basic income reaches people that welfare is supposed to help. With libertarian types, you start with the efficiency and non-bureaucratic character of a basic income. I have been very impressed by recent writing that emphasizes basic income’s ability to remedy asset inequality for people of color and women.

Now, I am very pleased to see more people who have already heard about basic income from someone. Sometimes they caught the wrong person for them. As we explain basic income, we will need to separate the policy (giving everyone an unconditional cash grant) from the project (which can range from left to right).

A quote like Altman’s can swing a listener in different directions. I know this from my social media work. I imagine people running different movies in their head. Some hear “new products and services and new wealth” and visualize start-ups and think it all sounds great. Others try to imagine a world working well with 90 percent of people not doing anything anyone else wants them to do and they just can’t see that working out well. Others hear this and worry that basic income is part of a larger scheme to organize our lives around Silicon Valley capitalists. To them, Altman seems to overly glorify the tech entrepreneur. Other writers are more desperate in labeling basic income a “neo-liberal plot”, which would make you laugh if you went to one of our Congresses. We would not want to merely swap one set of capitalists for another.

I have not met Sam Altman. His other statements show that he also finds basic income interesting because it directly answers a moral mandate to make sure people are clothed, fed, and sheltered. I highly recommend the rest of the podcast. My objective here is to explain why I think we ought to look at this quote charitably. I will show in what way I think his quote is true. I also want to propose an alteration that makes it much more palatable for those I see reacting negatively.

No One is Saying Ninety Percent of Society Will Hit the Couch

Altman is not talking about a whole society in which only 10 percent work. He is saying that even if we lose some work-time to lame leisure (pot and video games), we will make it back even if only 10 percent start up new enterprises. Nor is he saying that he knows that we will get one successful start-up for every nine lives lost to the coach. He is only saying that losing nine to the couch would be an acceptable price to pay if we gain a start-up, which would offer something someone wants and would also be offering jobs. This is very plausible.

Most people with a basic income will live a lot like they do now. They will have a more stable income. They will worry less about many of their friends and family. They will have a plan if they need to train for a job or pay bills between jobs. This cuts into the number of people who would choose the couch. Work can be a place where we get recognized for our talents and for our cooperativeness. And jobs pay money. In fact, you can still count on a basic income if you take on a job. And you can count on it if you change your mind.

The problem now is that employees have very few options when workplaces go sour. Basic income creates one option (work for no one) and enables people to survive while they search for and train for other options. This will increase pressure on workplaces to improve.

I used to be suspicious of most rhetoric surrounding markets. I think that was because so much of it ended up with a conclusion like “Therefore, government should do less/nothing.” I have come to value markets more and more. Now, I want them for everyone. A basic income secures the capability to participate in markets for everyone. There are many sections of the United States that get very little government or market attention. That would be less likely with a basic income in effect. You will also see more start-ups under a UBI because failing doesn’t risk losing everything. Most entrepreneurs now come from the upper one percent of our society. Whole communities aren’t going to see much startup soon if we wait for the elite to try to make money there.

Add Caregivers and Organizers To The Mix

Someone organizing a non-profit, a political organization, or even an informal social scheme fits under Sam Altman’s phrase of “new products and services and new wealth.” He is not confining his hopes to technological startups.

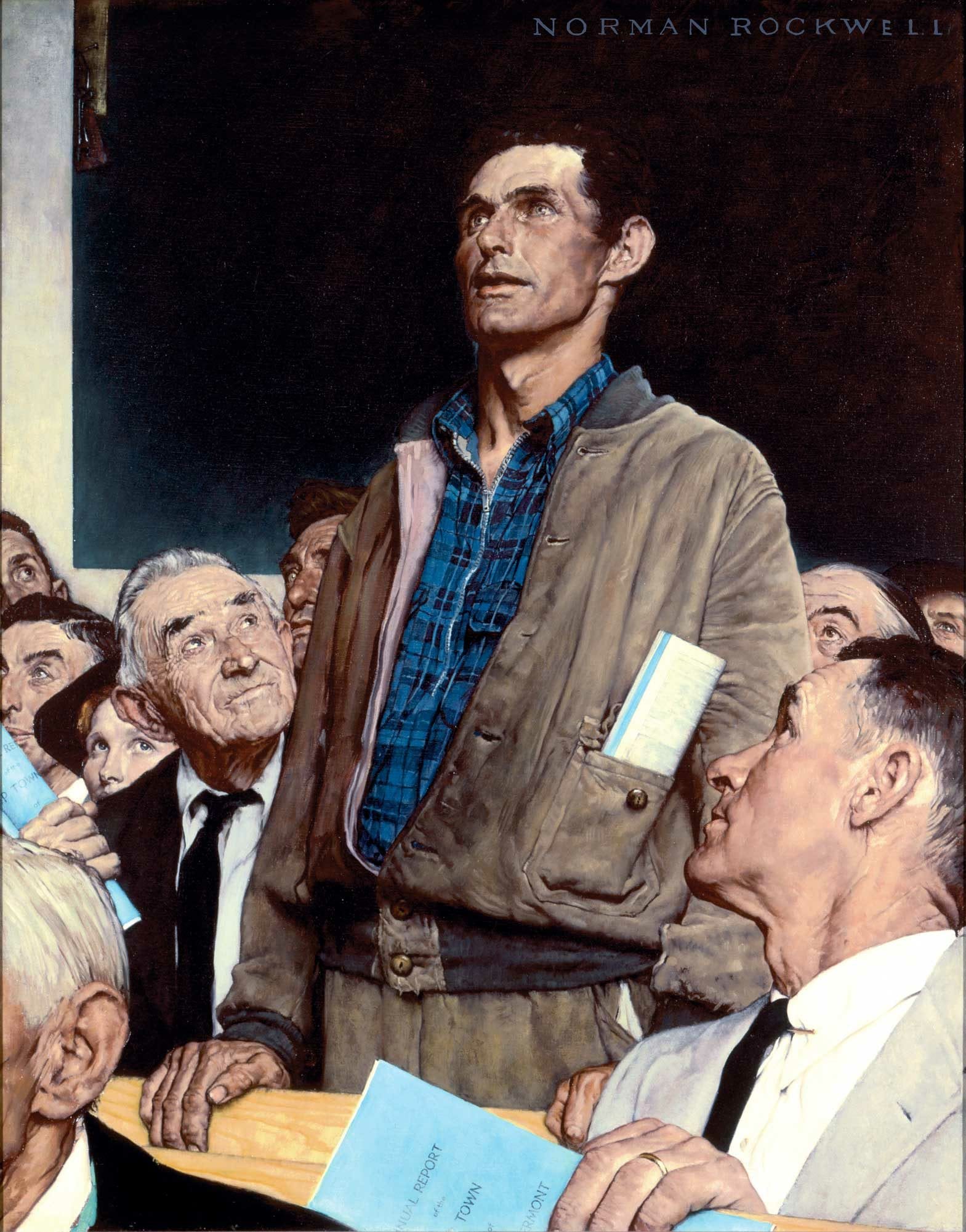

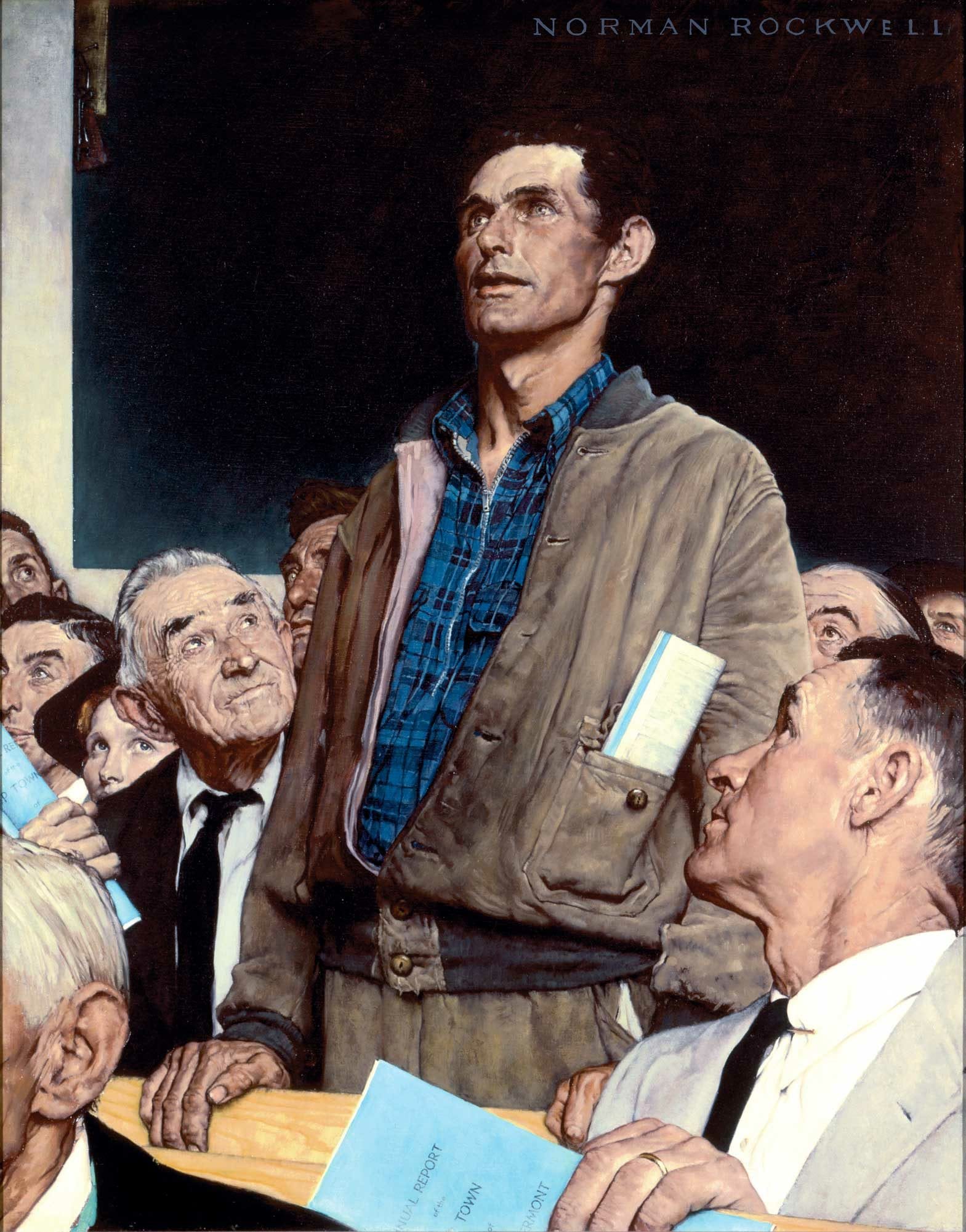

Robert Putnam’s book Bowling Alone, written in 2000, lays out the loss of social networks and the harm that has caused most Americans. These can be voluntary associations, political clubs, fraternal organizations, or sports leagues. Participation has declined as work-hours per household has increased. This means that many will look for alternative ways to interact with like minded Americans, especially when it comes to sporting events.

There is a strong link between organizational affiliation and many different metrics for happiness or meaningfulness. We also see more affiliation in communities that have more political power and that generate more market activity. (There is likely a causal loop there. Lack of power and lack of market options may often precede losses in organizational depth. And a lack of organizational depth may well often precede losses in money and power.) Social-capital comes hand in hand with capital-capital.

Michael Lewis and Eri Noguchi apply Putnam’s work, and combine it with survey data, to give us strong reasons to think that we would see improvements in civic networks as well. Declines in civic participations can be shown to coincide with an increase in work hours. People who value civic participation will have an option to do so.

If you want to know how a basic income will benefit society, let’s make it clear that we are including “organizers” within our understanding of “entrepreneur”. Our culture is one that has to be reminded of this. Once we expand our understanding, we can look around and see how many people are trying to participate in institutions that organize in pursuit of truth, justice, and beauty.

Examples will help here: church committees, symphony boards, rotary clubs, sports leagues, poetry circles, craft guilds, environmental organizations, identity-based youth groups, identity-based cultural organizations, music bands, theater companies, unions, political organizations, lobbying organizations, etc. This list could go on a very long time.

At this point, I want to share a little bit of what I learned as a community organizer in Arkansas for ACORN. Organizing is difficult. There are many ways in which it is not like entrepreneurship at all. You aren’t selling anything. All organizations have trouble finding this skill set. It is also difficult to get the resources together for full-time organizing. We would often hire someone who loved the mission of the organization but had to leave for pretty small increases in money. It might also prevent the loss of organizers to the for-profit sector.

Please note: I have noticed that a large section of the US internet is trying to malign the very term “community organizer” but my argument includes organization of groups I disagree with.

The ratio of organizers to members goes beyond the one to nine ratio that Altman imagines. About six of us at Arkansas ACORN served around 5,000 households if you are only counting dues payers. The community that responded to our work was larger than that. There were meetings every month. People debated goals and tactics. Political leaders were interviewed or protested. Organizations that despised us did the same things, though often with more funding from fewer people.

Every time I hear the term “couch potato” brought up as some sort of nightmare case for basic income, I remember that I sat on thousands of couches, urging people to get active, to get involved with their community’s decisions. I know that with a basic income, we would have had more organizers and more active members. Rival organizations would have had the same benefit. We will live in a more democratic place.

I am still involved in political work, even though I am not employed to do it. I also have been published as a poet and as a photographer, though not paid. You will find a lot of people working on magazines, readings, and websites in which the true, the good, and the beautiful are debated. A lot of people can see how to raise some money doing cultural, social, or political work but they can’t get to a decent level. A basic income would generate audiences for artists, philosophers, preachers-good and bad. A thriving art world is full of disputed art. A thriving philosophical culture will have disputed philosophical projects. We will live in a more interesting place.

Norman Rockwell “Freedom of Speech”

Finally, we should look at the decision to care for a family like we would a “start-up”. The “caregiver” has started a “career” that works for many people like a vocation. For each caregiver, there is at least one other person, usually more, benefiting in a meaningful way. Economists often do not count care for children and elders unless someone is formally paid to do it. A basic income would enable people to say no to employment if someone they love needs them. We will live in a more caring place.

In fact, Robert Putnam shows us in his research, as do Michael Lewis and Eri Noguchi in theirs, that the “stay-at-home” mom was often a civic association organizer as well.

More markets, more culture, more democracy, more care. This looks to be well worth investing 3% of our GDP and letting a few people stay home.

When I read the comments and notes that come with all basic income articles, I can see that some people would worry about people not working because of basic income. Basic Income enables people not to work. Kate McFarland points out that a basic income enables people to say no to all social useful activity. But we are far away from that. Some people will live incorrectly. Many people live incorrectly now. Basic income is a good bet for increasing socially useful work.

- More entrepreneurs means more people are offered employment.

- More organizers mean more people are being invited to venues where what is true, what is good, and what is beautiful are debated and plans are made.

- More caregivers mean more people are taken care of.

Therefore, most likely, for every couch potato, we will have better reasons than ever to get off the couch.

About the author:

Jason Burke Murphy teaches philosophy and ethics at Elms College in Western Massachusetts. He serves on the board of US Basic Income Guarantee Network and recently presented at their North American Congress. He helps with social media for US Basic Income Guarantee Network. He has written before for Basic Income News. His most read piece so far is “Basic Income as Proposal, as Project, and as Idea.”

by Furui Cheng | Aug 15, 2017 | News

The State Council of China released an Artificial Intelligence (AI) development plan on July 20, 2017, which aims to build a domestic industry worth almost $150 billion and positioning the country to become the world leader in AI by 2030.

There are three steps in the plan. By 2020, the Chinese government expects its companies and research facilities to be at the same level as those in leading countries such as the United States. After another five years it is aiming for a breakthrough in aspects of AI that will drive economic transformation. Then by 2030 China aims to become the world’s premier artificial intelligence innovation center, establishing the key fundamentals for a great economic power.

However, rapid development of AI solutions is not without its drawbacks. In June, Kai-Fu Lee, the chairman and chief executive of one of China’s leading venture capital firms Sinovation Ventures and the president of its Artificial Intelligence Institute, expressed concerns about the downsides of AI, particularly the potential for mass unemployment. He raised basic income as a feasible solution.

According to Kai-Fu, the AI products that now exist are improving faster than most people realize and promise to radically transform our world, not always for the better. They will reshape what work means and how wealth is created, leading to unprecedented economic inequalities and even altering the global balance of power.

He highlighted the challenges brought about by two specific developments: enormous wealth concentrated in relatively few hands and vast numbers of people out of work.

Part of the solution to the loss of jobs will involve educating or retraining people in tasks where AI performs poorly. These include jobs that involve cross-domain thinking such as the work of a trial lawyer, however, retraining displaced workers to perform these highly skilled tasks will not be feasible in most cases. There is more scope for people to occupy lower-paying jobs involving the nuanced human interaction that AI struggles to perform, such as social workers, bartenders and concierges. But here too there is a problem: how many bartenders does society really need?

The solution to the problem of mass unemployment, Kai-Fu suspects, will involve “service jobs of love.” These are jobs that AI cannot do, that society needs and that give people a sense of purpose. Examples include accompanying an older person to visit a doctor, mentoring at an orphanage and serving as a sponsor at Alcoholics Anonymous – or, potentially soon, Virtual Reality Anonymous for those addicted to their parallel lives in computer-generated simulations. In other words, the voluntary service jobs of today may turn into the real jobs of the future. Other voluntary jobs may be more professional and therefore higher-paying, such as compassionate medical service providers who serve as the human interface for AI programs that diagnose cancer. In all cases, people will be able to choose to work fewer hours than they do now.

In order to pay for these jobs, it will be necessary to take advantage of the enormous wealth concentrated in relatively few hands.

Kai-Fu Lee writes:

“It strikes me as unavoidable that large chunks of the money created by AI will have to be transferred to those whose jobs have been displaced. This seems feasible only through Keynesian policies of increased government spending, presumably raised through taxation on wealthy companies.

As for what form that social welfare would take, I would argue for a conditional universal basic income: welfare offered to those who have a financial need, on the condition they either show an effort to receive training or commit to a certain number of hours of “service of love” voluntarism.

To fund this, tax rates will have to be high. The government will not only have to subsidize most people’s lives and work; it will also have to revenue previously collected from employed individuals.”

More information at:

In Chinese:

Guo Fa, “State Council for a new generation of AI to inform development management“, Chinese State Council, July 8th 2017

In English:

Paul Mozur, “Beijing wants AI to be made in China by 2030”, The New York Times, July 20th 2017

Kai-Fu Lee, “The real threat of artificial intelligence”, The New York Times, June 24th 2017

Article Reviewed by