by Andre Coelho | Jun 8, 2017 | News

Kerry Frank, a consultant in research and analysis for Mondato, has recently written an article discussing the relation between basic income, government institutions and cryptocurrencies. A cryptocurrency is a digital currency that uses cryptography for security. Cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, are decentralized systems based on blockchain technology, information on which can be found over on VanillaCrypto.com. A lot of people use Bitcoin to trade stocks and shares online, as over the years, it has become a popular way to increase your income. Most people decide to look into cryptocurrency by visiting a trading site, yet others make the decision to look for something like this “used innosilicon a10 pro” to create their own digital currency and then selling them to the many sites. It could be a great way to be able to get stuck into the process of cryptocurrency. That being said, if you’d like to find out more about cryptocurrency trading, then researching trading applications such as the bitcoin revolution app could help you to further your knowledge of this growing field.

In the article, she argues that progression towards a basic income is only possible with a “comprehensive digitization across the board to manage administration and monitoring costs”. This is required on a global scale, since digitization has covered more ground in the Global North than in the Global South. For example, only 50% of all adult individuals globally have a registered bank account, according to the World Bank.

The article also points out that cash transfer programs, for example in India and Kenya, bring about increases in individuals’ willingness to take on loans, make savings or invest. Recent data from the GiveDirectly test pilot already shows that financial inclusion is a welcomed side-effect, since many participants would not have joined formalized financial networks if not for the experiment.

It is argued that cryptocurrencies are a viable means to disburse cash payments on a massive scale. Actually, this possibility has been presented and discussed before, in several articles. One such systems is Resilience, which uses redistribution and dividend pathways as a defining programming feature. However, only a few people are knowledgeable enough to use such a system, and even fewer who may understand its internal workings, as Kerry Frank also raises in her article. This constitutes, of course, a barrier to basic income implementation in a cryptocurrency version. For now, the cryptocurrency takeover of the world’s financial system is on hold. However, this could mean investing in cryptocurrency might still be lucrative to those aiming to take a slice of the pie in the near future.

Kerry concludes that cryptocurrencies and traditional government programs (of cash distribution) need not be mutually exclusive, while there are advantages and challenges with both approaches.

More information at:

Kerry Frank, “Universal Basic Income: G2P on steroids or an opening for cryptocurrencies?“, Mondato, April 25th 2017

J. Shapiro, “Can cash transfer programs help bring about financial inclusion?“, Microfinance Gateway, April 2017

Austin Douillard, “US/Kenya: New study published on results of basic income pilot in Kenya“, Basic Income News, March 27th 2017

Cameron McLeod, “BitNation: Recent advances in cryptocurrency see basic income tested“, Basic Income News, March 30th 2017

by Andre Coelho | May 28, 2017 | News

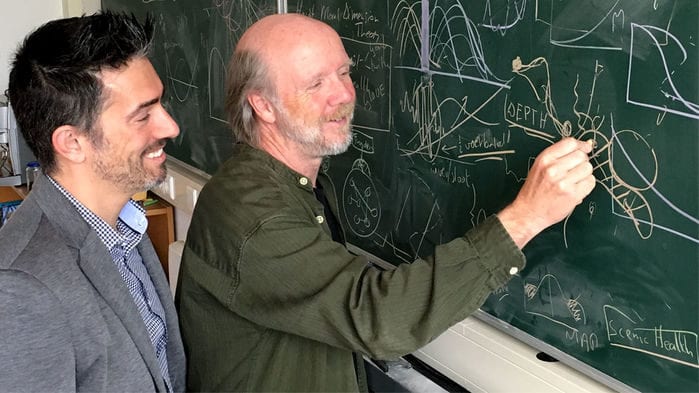

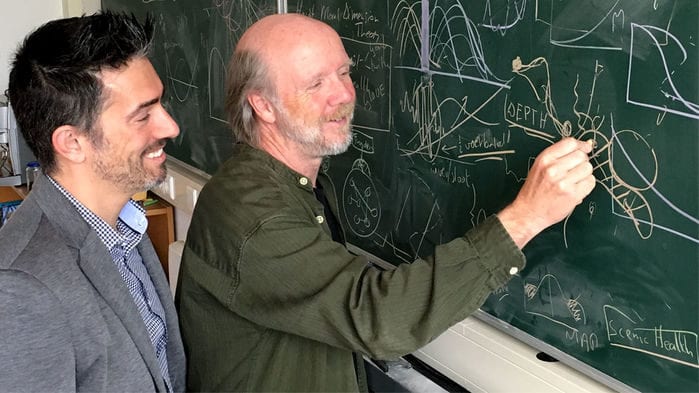

Vito Laterza and Jurgen de Wispelaere. Credit to: O Observador.

An event focused on the discussion about social policy in Portugal, and particularly about basic income (in Portugal mostly called unconditional basic income), took place at the Lisbon School of Law (University of Lisbon) on the past day 15th of May 2017.

The first part of the event featured Pierre Guibentif and Paulo Pedroso, both professors at ISCTE, University Institute of Lisbon. The former spoke favorably about basic income in a general sense, while the latter was clearly against it. Guibentif defended it was important to compare basic income to other forms of (conditional) income support, although he did not suggest the setup of an experimental pilot to test it. He, although highlighting basic income’s originality over other social policies, defended that it doesn’t per se defend social inclusion. He went on to say that its originality stems from an intent to generate social evolution, contrasting with minimum income schemes, that aim at alleviating most pressing inequalities but not to change the capitalist mode at its core. In his final remarks, Guibentif doubted basic income’s power to emancipate people, who may lack the capacity and/or knowledge to really pursue virtuous life paths. For that he suggested that the State should maintain and even strengthen specific programs to support citizen’s continuous learning in core areas as science, the arts and other humanities.

On the other hand, Paulo Pedroso questioned the relevance of basic income from the onset. Although he concedes that basic income is intended to be a correction of inequalities at birth (structural inequalitites), he remains skeptic about the capacity of the poorest segment of the population to structure their own lives and make a meaningful contribution to society. According to him, basic income will just keep them (the poor) marginalized and unfulfilled. Pedroso firmly stands that work is fundamental for a healthy society, and so basic income will just erase work’s importance as an identity driving force. Supporting a view of full employment, he views work as essentially related to paid employment, more commonly held as jobs. In an increasingly emotional exposition, Pedroso affirms that basic income is sure to be a vehicle for the destruction of the welfare state as we know it, in a reference to common right-wing views on the applications of basic income. He concludes stating that basic income “amounts to suicide”.

The presentation panel also included Olli Kangas, PhD and responsible for the basic income pilot project being run in Finland at the moment, while working for Kela, the social insurance institution of Finland. He essentially presented and justified the pilot project, which aims at avoiding social traps of several kinds – mainly bureaucratic, poverty and unemployment traps. He referred to some internal challenges, for instance unions in Finland, which are categorically against basic income in fear of losing affiliates in the near future. These unions congregate around 70% of the work force in Finland. Kangas explained that the value used in the experiment (560 €/month) was set in order to match the average amount recipients were already receiving from Kela. He also said that, other than employment, this first experiment would also measure the use of prescriptions, medical treatment and income registration. This would be done without interviews or questionnaires, in order not to influence the experiment’s output. To conclude, Olli Kangas announced that Kela was already planning a larger, more profound experiment in Finland. This time it would be national in range, with a larger sample taken from all people on low incomes and experimenting with more tax models.

Olli Kangas. Credit to: Observador.

Vito Laterza was also a panelist, and enthusiastically defended the basic income concept, while clearly highlighting some of its challenges. He approached the issue in a “back-to-basics” fashion, recalling the “original idea” of basic income: to liberate people. Laterza went on to describe the present-day labor market as “very segmented” and in which several lines of separation are drawn – sexual, racial, disability, etc. To counteract that unfair and segmented labor market he spoke of “cooperative security”, which intends to build on the welfare state in a non-discriminatory way. He also alerted that basic income must not be seen as “just cash”. That monetization of life tendency is, according to him, extremely dangerous, and so the implementation of basic income must be guided by a freedom-for-all mindset, without destroying the beneficial aspects of the welfare state.

To close this event’s first part, Jurgen De Wispelaere spoke about the necessity of basic income being part of a landscape of policies, most of them already in place within the context of the welfare state. According to him, a policy like basic income can be a generator of other policies, and he made a case for a possible integration between “active” and “passive” social measures. Typically, “active” policies like social investment try to prepare people for the marketplace (where commodification occurs), and “passive” ones like basic income are about de-commodification. Jurgen considers that these policies may be complementary, rather than opposites. He defends that basic income can also be an activation tool, helping in removing social traps – unemployment, bureaucratic and poverty traps – so liberating citizens to pursue education and/or other qualifications. In the same vein, basic income can also provide better conditions for young age learning, which will further the potential for a productive adulthood. He goes on to sustain that basic income also “activates” people to move from “crappy jobs” to better, more meaningful activities. As a final remark, Jurgen’s activation argument also involves gender equality issues, assuring that a basic income can particularly help women to get activated.

Roberto Merrill and Sara Bizarro, also present, shortly listed their version of the advantages and disadvantages of introducing a basic income, opening the session for questions and answers with the audience. The debate that followed revolved around the usual arguments against basic income: disincentives to work, difficulty in financing and the capture of the idea by the far-right.

The second part of the event was setup as a debate roundtable. Several personalities of the academia and politics were present, such as Carlos Farinha Rodrigues, Manuel Carvalho da Silva, Renato do Carmo, Martim Avillez Figueiredo, André Azevedo Alves, André Barata, Luís Teles Morais and the Minister of Work, Solidarity and Social Security José António Vieira da Silva.

José António Vieira da Silva. Credit to: Observador.

Apart from known defenders of basic income in Portugal, as André Barata and Renato do Carmo, all others showed reserves, in several degrees. Among these there was an overall sentiment that it may still be better to improve on existing conditional social assistance, than to risk a free-from-obligation cash transfer program and end up with a largely idle population. Basic income implementation at the European level was referred several times, in what could be a signal of reluctance in spearheading the concept, leaving that responsibility to supranational entities like the European Community. That is also the opinion of the minister Vieira da Silva, who is concerned about how to communicate the basic income concept to the population at large, and about the risk of creating a cleavage in society between those who work (have jobs) and those who do not (do not have jobs). He has also expressed his belief that there will be no shortage of work (intended as jobs) due to technological innovation, referring to past “revolutions”. However, Vieira da Silva has agreed, along with others, that a wider, more profound discussion about work is necessary in our society.

André Barata summed up the feelings in the air with the following sentence: “There were many reticent speeches, but I haven’t seen any downright opposition”.

Help provided by Eduardo Currito.

More information at:

Event information at the Lisbon School of Law website

In Portuguese:

Agência Lusa, “Vieira da Silva admite “sentimentos cruzados” sobre o Rendimento Básico Incondicional [Vieira da Silva admits “mixed feelings” about basic income]”, Diário de Notícias online, May 15th 2017

Edgar Caetano, “Um salário sem trabalhar. Faz sentido em Portugal? [An income without work. Does it make sense in Portugal?]”, Observador, May 15th 2017

by Andre Coelho | May 20, 2017 | News

A crowdfunding campaign was just launched for the new documentary, “The Mincome Experiment”. Kreytor, a recent web platform designed for “showcasing, curating and crowdfunding creative work” launched the campaign on May 1st, 2017, only five years after the platform was created by the documentary producer Vincent Santiago, an independent artist from Winnipeg, Manitoba (Canada). Over the last five years Vincent has interviewed experts in the field and gathered information for the documentary.

Funds to support the documentary is now officially open at Kreytor’s Mincome project webpage. Also, the launch provides a short video (below) that introduces the documentary, while providing background and context on basic income experiments conducted in Dauphin, Canada, in the 1970’s. Recently, the experimental results from Dauphin have been reported on more extensively, after having been archived for decades.

https://vimeo.com/214118425

More information at:

Kate MacFarland, “NEW LINK: Basic Income Manitoba website“, Basic Income News, October 27th 2016

Kate MacFarland, “MANITOBA, CANADA: Winnipeg Harvest pushes for basic income“, Basic Income News, April 6th 2016

Wayne Simpson, Greg Mason and Ryan Godwin, “The Manitoba Basic Annual Income Experiment: Lessons Learned 40 Years Later,” Canadian Public Policy, 2017

by Andre Coelho | May 18, 2017 | News

The United States Carbon Tax Center (CTC) has just released a new report, showing that eight USA states are ready to implement a carbon tax, and twelve others are building towards it. This comes in a time when the Trump Administration unwinds recent progresses related to climate change policy in the USA.

The CTC has prepared a toolkit, designed to help advocates for carbon taxes win support in their respective states. CTC’s director Charles Komanoff sets the tone of urgency: “now we need to get it to as many people as possible in the states where we have the greatest chance of victory, and fast”.

The report examines the economic, political and environmental situation in all 50 USA states, in an attempt to determine the regions where the best possibilities are to enable policies that can dramatically reduce carbon emissions. In the report and elsewhere, serious consideration is being given to turn this carbon tax revenue into a social dividend, or a kind of basic income.

Already in the Canadian province of British Columbia a carbon tax policy is in place since 2008, and has been very successful at cutting carbon emissions. According to another CTC report, released in 2015, the British Columbia region has seen per capita carbon emissions decrease 3.5 times faster than the rest of Canada, while still growing in an economic sense. Based on this successful implementation, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau progressive government is determined to take carbon taxation onto the national level. In October 16th 2016, Trudeau boldly told MPs in the Canadian House of Commons (as reported in the CPC website) : “If neither price nor cap and trade is in place by 2018, the government of Canada will implement a price in that jurisdiction”. The idea is to start at 10 CAN$/tonne CO2 in 2018, gradually increasing up to 50 CAN$/tonne CO2 in 2022.

More information at:

Courtnet Weaver, Barney Jopson and Ed Crooks, “Trump unwinds Obama actions on climate change”, Financial Times, March 28th 2017

Yoram Bauman and Charles Komanoff, “Opportunities for carbon taxes at the state level”, Carbon Tax Center, April 2017

by Andre Coelho | May 16, 2017 | News

Back in 2014, Johan Bollen and four other colleagues published an EMBO report, presenting a new and radical approach to scientific funding. Since then, Johan has paired with Marten Scheffer so as to develop and communicate further the notion of SOFA – Self Organized Fund Allocation. Scheffer has recently led the Dutch parliament to ask the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) to start a SOFA test pilot.

But what is a SOFA? It is a new way to allocate funds for scientific research. The traditional approach usually means a funding agency receiving many applications, which entail a time-consuming process in itself. Plus, it costs a large percentage of the funding amount to run and manage this top-down driven system. According to a recent article on the issue, by Jop de Vrize, that percentage can be as high as 25%. On top of that, it has been proven highly inefficient, since the success rate of these application is usually below 20% (19.1% in 2016 according to the US National Institutes of Health, and 11.3% at the European Research Council Starting Grants for the same year). The result is that some scientists get lots of money, while a lot of others get a fraction of that money, or even nothing.

The new SOFA funding scheme is, at its core, a distributed, self-allocating system. The funding agency still attributes a certain amount of money to a research community, but then, instead of going through a cumbersome, time-consuming, unfair and inefficient process of distribution, the idea is to get the researchers themselves to allocate funds to other researchers. Specifically, the SOFA system would attribute an equal, unconditional amount of money to each researcher – a certain earmarked value by the agency, divided by all researchers in the community – and then each one would donate 50% of their present and past funding [1] to other scientists, trusting their best judgment.

Proposed funding system (Johan Bollen et al.)

Of course, this new system is not devoid of problems, or potential challenges. Freed to allocate 50% of their research income to other scientists, researchers could choose to give money only to their friends, collaborators or mentors. Also, the problem of the money not reaching those who are needing it the most may still arise, only partially offset by the unconditional amount that will be equally distributed (50% of each year’s grant). However, Bollen and Scheffer are confident, after running many simulations, that “rather than converging on a stationary distribution, the system will dynamically adjust funding levels to where they are most needed as scientists assess and re-assess each other’s merits”. They also agree that the system would have to be include programmed features to avoid self-attribution and hide funding decisions (to keep decisions unbiased), for instance. An important feature of the SOFA system is that no one individual researcher has access to enough information so as to try and influence the attribution mechanism (contrary to the present system, which is more easily politically malleable).

The unconditionality associated with the SOFA scheme, plus its widely-distributed nature draws some similarities with the basic income concept. Basic income, as defined at the Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN), rests on the independence of income and work-status, or even willingness to work. Granted, the SOFA scheme implies that the money is distributed among scientists, devoted and committed to scientific work, with clear and established study plans. However, it is also clear that some of the previous conditions associated with funding decisions – mainly a discussable notion of merit coming from a very small group of peer-reviewers who end up allocating the grants – will collapse if SOFA is introduced. Another similarity with basic income proposals has to do with de-complexification of the attribution system, also reducing its overhead costs, as a function of both distributing 50% of the grants unconditionally and putting in the hands of the researchers themselves the responsibility of distributing the other half of each grant. In the basic income arena, that advantage usually takes the form of reduced costs with social security management, and lowering complexity through existing program’s extinction and remodeling. A third similarity has to do with trust. Unlike the present system, SOFA inherently trusts researchers to allocate 50% of their grants to others. This trust is also present in most basic income proposals, which allow recipients to spend their basic income as they see fit, hence furthering their personal freedom and capacity to more efficiently solve problems in their own lives.

The SOFA scheme has been presented to Eppo Bruins, a member of the Dutch House of Representatives, who proposed a call for a SOFA test pilot in June 2016, which was approved by the parliament. However, the NWO, the agency which would start and manage the experiment, has resisted the initiative. According to Scheffer, that is understandable, since “if applied universally, the novel system would make the agency redundant”.

Notes:

[1] – Management of past funding options is still not included in the proposed model, but is considered important by the authors, to better use of unused funds.

More information at:

Johan Bollen, David Crandall, Damion Junk, Ying Ding, Katy Börner, “From funding agencies to scientific agency”, EMBO reports 15 (2), September 7th 2014

Jop de Vrize, “With this new system, scientists never have to write a grant application again”, Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science), April 16th 2017