by Guest Contributor | Nov 21, 2016 | Opinion

Original post can be found at TRANSIT

Written by Bonno Pel & Julia Backhaus

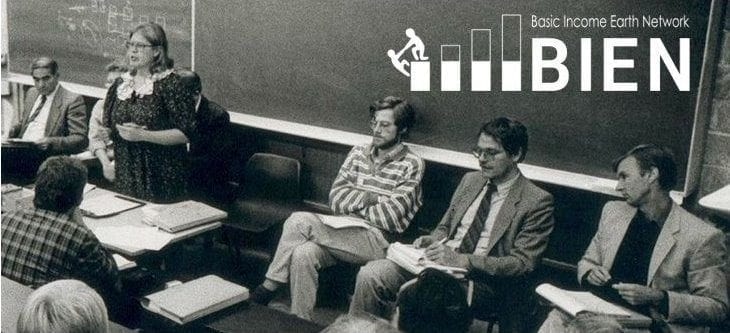

On Saturday October 1st 2016, the Basic Income Earth Network celebrated its 30th anniversary at the Catholic University of Louvain in Louvain-la-Neuve (Belgium). The picture shows the founding meeting in 1986, but is also quite applicable to BIEN 30 years later. The conference was held at the same location and many of the founders and their fellow militants met in good atmosphere to commemorate the early beginnings of the network. Together with other scholars and generally interested people, they discussed current developments in science and policy and ‘the way forward’ for the basic income movement.

picture source

An unconditional income for all

First, the picture is telling for the ways in which BIEN pursues transformative social innovation, namely through the development, discussion and dissemination of persuasive “new framings” and “new knowings”. The seminar room in the picture gathers several individuals who by now have become eminent scholars in economy, social philosophy or sociology. Over the course of three decades and together with activists, politicians and citizens, BIEN members have developed a whole complex of arguments, evidence and framings around the basic income. The idea itself is simple: An unconditional, individual income entitlement, more or less sufficient for fulfilling basic needs, promises real freedom for all.

It offers individual empowerment in the form of income security and the material conditions for a self-determined existence in society, but it is also in many aspects about changing social relations: between men and women (as the conventional breadwinner model is challenged by individual income entitlements), between employed and unemployed (as stigmatization lessens when entitlement is universal rather than for the ‘unproductive’ only), and between employee and employer (the latter’s possibilities to exploit the former are decreased by the basic income security). In current institutional-ideological constellations, the idea of a basic income is bizarre and outrageous for rewarding jobless ‘free-riders’. Apparently relinquishing hard-earned social security arrangements, BIEN members met (and continue to meet) with tough press, sidelining them as ‘irresponsible freaks’. Yet the power of BIEN members’ socially innovative agency resides in showing that it is actually many common ideas about work and income that are outdated, and harmful even.

Claus Offe (credit: Enno Schmidt)

Impressive examples of outdated conceptions were provided by prof. Claus Offe, who argued that we do not earn our income, as commonly believed. Wage flows from labour that forms part of ever-extending production chains of individuals and machines. The availability of jobs fluctuates cyclically, and independently from individuals’ employability efforts. Moreover, the current productivity in highly industrialized countries is possible because ‘we stand on the shoulders of giants’. It is largely inherited from previous generations. So it is rather the current insistence on employability, on meritocracy and on ‘earning one’s income’ that is out of tune with economic reality. Production has become post-individual, and this requires a matching social security system. Harmful effects of a capitalist system that ignores its obviously collective character through individualist ideology include blaming the losers and accepting precarious conditions for some. Economist Gérard Roland outlined how the basic income provides a better trade-off between labor market flexibility and precariousness than current social security arrangements. Sociologist Erik O. Wright views the basic income as a “subversive, anti-capitalist project”. He expanded how the concept allows moving on from merely taming to escaping the globalized, capitalist system. For him, the basic income can provide the basis for numerous social innovations that also the TRANSIT project considers, such as social and solidarity economy initiatives or co-operatives.

BIEN thriving on internal differences: many streams forming a river

Second, based on the variance of people’s clothing, the picture above also visualizes how BIEN has developed as an association of very different individuals. At the conference various founding members recalled the routes they had traveled towards the transformative concept. They arrived at the idea on the search for liberalist re-interpretations of Marx, through feminist commitments, when rethinking meritocracy, as a response to the structural unemployment of the time, or as a logical conclusion of a transforming and ‘robotizing’ economy. The forthcoming case study report on BIEN by yours truly spells out in more detail how these different little streams came to ‘form a river’, as expressed by a founding member. The internal differences between the generally principled and intellectually sharp BIEN members led to fierce debates, it was recalled. According to a longstanding motor, evangelizer and lobbyist for the basic income, BIEN has only survived as a network for members’ capacity to ‘step back a bit’ from their ideological disputes at times, and to recognize what united them. BIEN even thrived on its internal divisions. It functioned as a discussion platform, and helped to institutionalize basic income as a research field. Since 2006, there is even an academic journal on this example of transformative social innovation: Basic Income Studies.

Evolving communication: spreading the word

Philippe Van Parijs (credit: Enno Schmidt)

Third, the black and white photo immediately suggests how different the world was three decades ago. At the time of founding, network members and conference participants from various countries had to be recruited through letters. Initially, the newsletter was printed out, put in envelopes and stamped, for which members gratefully sent envelopes with pesetas, Deutschmarks and all the other European currencies, subsequently converted at the bank by standard bearer professor Philippe Van Parijs and his colleagues. Today’s e-mail, website and Youtube recordings obviously make a crucial difference when it comes to facilitating discussion and spreading the word fast and wide – especially for this social innovation that primarily travels in the form of ideas. The presentations on the history of basic income underlined the significance of the communication infrastructure. The history of basic income can be conceived of as a long line of individuals working in relative isolation, often not knowing of others developing similar thoughts and blueprints. The evolution of BIEN very instructively shows the importance of evolving communication channels and knowledge production for transformative social innovation – critical, weakly-positioned, under-resourced individuals no longer need to re-invent the wheel in isolation.

BIEN, a research community? Ways forward

A fourth, telling element the picture above is the confinement of the seminar room. There have been discussions about BIEN’s existence as a researchers’ community, with the expert-layman divides it entails (during this meeting of experts, yours truly fell somewhat in the latter category). There are in fact also other networks of basic income proponents that have rather developed as citizen’s initiatives and activist networks. BIEN, as a network that can boast such a high degree of conceptual deepening and specialization, is illustrative for the ways in which it remains confined in its own room. It is significant in this respect that the current co-chair brought forward two lines along which the network should reach out more. First, BIEN should be more receptive towards and engaging with the various attempts to re-invent current welfare state arrangements. While this may imply using a more practical language and taking off the sharp edges it may yield real contributions to social security. Often these change processes (regarding less stringent workfare policies, for example) are not undertaken under spectacular headings and transformative banners, but they involve application of some basic income tenets such as unconditional income entitlements. A second line for outreaching confirms the importance of comparative research into transformative social innovation like TRANSIT: The co-chair highlighted that BIEN will explore and develop its linkages with other initiatives, such as Timebanks and alternative agriculture movements more actively.

Basic income: a ‘powerful idea, whose time has come?’

Fifth and finally, the seminar room setting depicted in the photo raises attention to the knowledge production that BIEN has been and is involved in. The socially innovative agency of its members can be characterized as ‘speaking truth to power’. Basic income activism has taken the shape of critiques, pamphlets and counterfactual storylines (Thomas More’s ‘Utopia’ being a 500 year-old example), but also featured modeling exercises, forecasts, and economic evidence to support the case. BIEN members’ key resource is their expertise. Moreover, considering the strong arguments and evidence gathered in favor of the basic income over the past decades, there are reasons to be confident in basic income ending up as the ‘powerful idea, whose time has come’. As described in Pel & Backhaus (2016) and currently considered further, it is remarkable how much BIEN seems to have developed in line with the trend of evidence-based policy. The commitment to hard evidence gives rise to an important internal discussion on the recent developments towards basic income-inspired experimentation (such as in Finland and in the Netherlands). The common stance of BIEN members is that these experiments fall short of providing any reliable evidence for their limited duration and scope, and for the system-confirming evaluative frameworks that tend to accompany them. However, there is also a somewhat growing attentiveness to the broader societal significance of experiments and pilots in terms of legitimization, awareness-raising and media exposure. It is therefore instructive for the development of TSI theory to study the basic income case for the new ways in which ‘socially innovative knowings’ are co-produced and disseminated.

About the authors:

Bono Pel (Université libre de Bruxelles; bonno.pel@ulb.ac.be) and Julia Backhaus (Maastricht University; j.backhaus@maastrichtuniverstiy.nl) are working on TRANSIT (TRANsformative Social Innovation Theory), an international research project that aims to develop a theory of transformative social innovation that is useful to both research and practice. They are studying the basic income as a case of social innovation, focusing on national and international basic income networks and initiatives.

by Kate McFarland | Sep 26, 2016 | News

On September 9, the New South Wales Fabians hosted a discussion of universal basic income in Haymarket.

The event featured a lineup of three speakers. First, Ben Spies-Butcher (Department of Sociology at Macquarie University) argued that Australia should pursue a universal basic income as a way to provide individuals with more freedom and control over their own lives and work. Next, Peter Whiteford (Crawford School of Public Policy at Australian National University) outlined the cost of a UBI. Finally, Louise Tarrant (formerly of United Voice) laid out many of the pros and cons of the policy. The three individual speeches were followed by the question and answer session with the audience.

About 80 to 90 people attended the event, which had been widely publicized on social media. Lachlan Drummond, president of the NSW Fabians, states that this crowd was the largest that the group has seen at any of its events over the past three years.

Among the unexpected attendees were two Italian members of the Five Star movement, who video-recorded the entire event:

The NWS Fabians have also released an audio-recording of the event as a podcast.

Drummond explains that several factors prompted the NSW Fabians to organize and host the event. First, the Fabians were interested in opening discussion of UBI simply because it is a “big transformative economic idea” that is already being talked about by the British Labour Party and some think tanks in the UK, as well as by other groups in Europe, Canada, and elsewhere. Second, the group saw a gap in Australian political discussion surrounding UBI:

We’ve seen some far-left and even some right wing groups talking about it here in Australia but none on what we might call the “mainstream centre left”. We wanted to help push that debate along. We know there are people in both the Greens and the ALP [Australian Labor Party] who are keen on the idea, but as yet we hadn’t seen one event where everyone was all brought together to discuss it.

Third, Drummond notes that many members of the Fabians are personally undecided on the issue of UBI–and yet, previously, UBI had never been given a fair hearing at any NSW Fabians event. When previous guest speakers had broached the issue, their comments were negative and dismissive. Notably, at a March event on The Future of Work, Dr. Victor Quirk of the University of Newcastle spoke against UBI in favor of a return to full employment.

Not content with such a swift rejection of UBI, Drummond said that the NSW Fabians “wanted to look at the policy in a systematic way–to go through the positives and negatives, to look at the numbers, and the political realities, and whether pilot studies have shown it to actually work”.

According to Drummond, the main goal of the event was to leave the audience better informed about the issues surrounding UBI–both moral and practical–and that, by this measure, the event was a “big success”:

I think when you see a big progressive idea like this, it can be easy to jump on it and say it’s a great idea without knowing the arguments and practicalities (or even some potential alternatives).

Ben Spies-Butcher was great on the moral arguments, and how it should interact with other parts of the welfare system. Peter Whiteford gave us some useful numbers on how much it would cost and what pilot studies had actually discovered. Louise Tarrant was also very clear headed on the positives and negatives, both practical, economic and political.

We also had great impromptu contributions from Eva Cox on shorter working hours, and Luke Whitington who rebutted the argument about inflation by stating we are currently in a deflationary environment, and by outlining some creative and progressive ways it could be paid for. The audience was really engaged and asked great questions.

Luke Whitington, Deputy Chair of the NSW Labor Party Economic Policy Committee, found it “well-organized” but believes that all three features speakers overlooked one of the most important reasons to support UBI:

None of the speakers talked about deflation, either in relation to the specific term of falling prices, nor in relation to the more general term for a long term low growth period, as exemplified by Japan since the 90s and the world in the 30s, and in milder form, advanced economies since the 70s, compounded and accelerating now with financialisation and automation. That none of the panel speakers raised the necessity of basic income as a counter deflationary mechanism was a pity, especially as Yanis Varoufakis’ speech on the topic has been on YouTube for a number of months. They did, however, inform the audience on a wide range of ethical and economic issues that a BI would affect.

As Drummond pointed out, though, Whitington was eventually able to broach the issue of deflation himself, in response to issues raised by Tarrant. On Whitington’s view, based on his experience as an organizer in the Labor Party, the most politically viable approach to a UBI in Australia is to promote the policy as a counter-deflationary measure and to support its financing through a sovereign wealth fund. This, he notes, was not stressed by the pro-UBI speakers at the NSW Fabians event.

In Australia it would be much more difficult to argue that unemployment benefits be paid without any activity or eligibility tests (which Spies Butcher correctly pointed out would immediately improve the lives of hundreds of thousands of people currently stuck in the welfare ‘safety’ net), than to set up a fund that collected mineral or other revenue and distributed it equally to all citizens as a dividend.

Douglas Maclaine-Cross, who has previously worked with Whitington to promote UBI, also attended the event. Maclaine-Cross was struck by the apparent level of agreement: “Generally nobody seemed to object to the policy [UBI]; on the contrary it seemed that most people were very keen on it”:

[P]eople generally agreed that it could be afforded though it would of course mean raising more revenue. The estimates and suggested amounts involved a more generous payment than I was thinking of, which I took as a positive sign. …

From the floor there was a plea on commercial grounds from a libertarian. There were a few very positive and inspiring comments. I heard the word utopia mentioned a few times. There seemed to be a consensus from the audience that growing inequality was a very real problem and needed to be addressed somehow. So perhaps it was a case of preaching to the choir. However having made the case to people from a broad spectrum of politics myself, there is a chance for bipartisan support; so I have very high hopes for the policy in Australia.

by Kate McFarland | Aug 30, 2016 | News

The Australian Fabians — Australia’s oldest left-leaning political think tank — will host a discussion and debate about universal basic income in Haymarket, NSW on September 9.

Speakers include Ben Spies Butcher (Senior Lecturer at Macquarie University), Peter Whiteford (Professor at ANU Crawford School of Public Policy), and Louise Tarrant (former National Secretary of United Voice).

Luke Whitington, Deputy Chair of the NSW Labor Party Economic Policy Committee, reports that interest and discussion surrounding has UBI has been on the rise within Australia’s Labor Party. Whitington sees the Fabians’ event as exemplifying this new trend.

The labour movement in Australia is getting serious about basic income. It’s great to see the Fabians facilitating this debate. The motion calling on the ALP to investigate a basic income is gathering momentum in the Labor Party branches. The next NSW and National Conferences will see a strong push for the ALP to investigate a basic income.

Douglas Maclaine-Cross, a Sydney-based software engineer who will be attending the meeting, remarks:

I’m just looking forward to the meeting, and getting an idea for how much support there is for it. Finding out if there are any concerns from people I’m not yet aware of. The prospect of finally having a way of solving out-of-control inequality, that people can rally behind has given me hope.

There are some additional signs that interest in UBI is increasing throughout Australia. In June, for instance, a Productivity Commission of the Australian Government released a research paper on “digital disruption” in which UBI was brought up as a potential solution to economic disruption caused by technological change. The Australian Pirate Party has endorsed a basic income (in the form of a negative income tax), also in June of this year, and one of the newest books in Palgrave Macmillan’s Exploring the Basic Income Guarantee series contains essays concerning the implementation of a UBI in Australia.

For more information about the event on September 9, see the website of the Australian Fabians.

Photo CC BY-NC 2.0 Emmett Anderson

This basic income news made possible in part by Kate’s patrons on Patreon

by Kate McFarland | Aug 10, 2016 | News

On July 13, the Pakhuis de Zwijger, in collaboration with the cultural institution Goethe-Institut Niederlande, hosted a basic income event in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

The event began with a few words from Anne van Dalen, who works as an artist in the Hague and was selected earlier in the year as the Netherlands’ second recipient of a crowdsourced, year-long basic income. Van Dalen reported that she has become more motivated since she began receiving the basic income, working longer hours than ever before, now that she is no longer “depressed about being a poor artist.”

Next, Sascha Liebermann, Professor of Sociology at the Alanus University of Arts and Social Sciences, reviewed the history of the basic income movement in Germany, including his own co-founding of the initiative Freedom not Full Employment.

Following Liebermann, Raymond Gradus, Professor of Public Economics and Administration at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, delivered an argument against unconditional basic income and in favor of participation income (driven primarily by concerns about reciprocity).

The last individual speaker was Ronald Mulder, the founder and secretary of MIES (Maatschappij voor Innovatie van Economie en Samenleving), the Dutch non-profit organization responsible for crowdfunding basic incomes for individuals like Anne van Dalen. Event organizer Bahram Sadeghi interviewed Mulder about his inspiration for creating MIES and his reasons for supporting basic income.

These short presentations were followed by a roundtable discussion, in which Sadeghi led a debate and conversation between Liebermann, Gradus, Mulder, and — as a new guest for this part of the event — Leisbeth van Tongeren, a Dutch MP from the Green Party.

The event was video-recorded, and the video is available on-line at Pakhuis de Zwijger’s website: “Free Money Society”

Photo from Goethe-Institut Niederlande.

by Guest Contributor | Jun 20, 2016 | Opinion

The level of Basic Income (BI) is a matter of heated debate in discussions of BI for national implementation, investigating the level at which BI would be ‘high enough’. There is also growing dispute regarding ‘partial’ vs. ’full’ BI. This was the central topic of investigation at this year’s BI conference in Maastricht in January. The following calculations, using a common formula and comparing BI levels for 24 European/OECD countries, aim to assist in the resolution of this debate.

We don’t want to make the system worse than it is. It’s logical, then, that the minimal level of BI should reach, at least, the level of current Social Assistance (SA): we could call this ‘partial’ BI. All BI proposals included in this analysis satisfy this condition.

It follows that implementation of a BI close to the level offered by the current social security system (e.g., the SA level) implies budget neutrality in countries with a more universal system.[1] This follows the argument “If we can afford our current welfare system, we can afford basic income” that Max Ghenis has well elaborated. These proposals might be socially more acceptable, given that the change would be ‘minimal’.

So, if the level of SA in a country indicates 1) the socially acceptable level of social aid and 2) the first estimation of the social welfare budget, BI at the same level would likely be the most financially and socially affordable solution, offering the shortest implementation time frame. Proposals for Slovenia[2], Hungary[3] and Finland[4] belong to this category.

On the other hand, the level of BI should be high enough to ensure a material existence and participation in society. We assume this when we argue that BI should be at least at the level of the current Poverty Threshold (PT): we could call this ’full’ BI. BI at such a level would probably fulfill the role of an emancipatory welfare system.[5] Proposals for Switzerland[6] and the Netherlands[7] fit into this second category.

The question is, how costly are lowered aspirations regarding a ‘partial’ BI level (e.g., in Slovenia, Finland and Hungary) in service of affordability and/or social acceptance in the foreseeable future? Will we achieve anything? As the microsimulation in Slovenia demonstrated, however, even a partial BI proposal (budget neutral, well below PT and above SA) proved to be: 1) better for the majority, 2) the same or better for the more vulnerable and 3) better for the lowest deciles. The Hungarian BI proposal seems to draw similar conclusions.

To serve discussion regarding the level of BI in different countries, a common formula (similar to that used for the Slovenian proposal) was used to calculate the levels of BI proposed in various countries.

Formula: BI = an average of three components:

- Social Assistance for a single person with no children: Indicates the currently acceptable minimal level of social aid (and the ‘budget’ of the current social security system).

- 1/2 of the Poverty Threshold at the point of 60% of the median income: Takes into account income distribution and the risk of poverty.

- 1/3 of average net wages: Takes into account the ‘value of work.’

A table with Basic Income calculations for 24 European and OECD countries allows us to draw comparisons across and within countries regarding: the social protection system (e.g., SA), the average wage (AW), the poverty threshold (PT), BI calculations using the same formula (both in national currencies and euro) and different BI proposals. It’s very important to note, however, that in countries where the level of SA is already higher than the BI calculation, the existing SA should be taken as a starting point. BI proposals for Finland and the Netherlands belong to this group.

Such BI calculations (that are above SA & ‘budget neutral’ & below PT) could serve BI discourse as the first benchmark:

- at which we could expect results that would be: a) better for the majority, b) the same or better for the more vulnerable and c) better for the lowest deciles;

- of the BI level calculation for countries that, as yet, have made no BI calculations;

- to evaluate competing national proposals;

- to evaluate proposals across countries;

- to evaluate existing social security systems, investigating by how much they diverge from this preferable solution;

- of common European social welfare solutions made by the people (of 99%) for the people and not from the EU elites.

Valerija Korošec: PhD in Postmodern Sociology, MSc in European Social Policy Analysis. Author of (eng) UBI Proposal in Slovenia (2012) sl. Predlog UTD v Sloveniji: Zakaj in kako?(2010). Co-editor UBI in Slovenia (2011). Member of Sekcija za promocijo UTD. Member of UBIE. Slovenian representative in BIEN. Fields of expertise: poverty, inequality, sastifaction with life, social policy anlaysis, gender equality, ‘beyond GDP’, paradigm shift, postmodernism, UTD, basic income. Slovenian. Born 1966 and raised in Maribor. Lives in Ljubljana. Employed at the Institue of Macroeconomic Analysis and Development (Government Office of Republic Slovenia). Views under my name are my own. @valerijaSlo

Footnotes:

[1] All included countries have a universal SA system, except: 1) Finland, Germany, Belgium, Estonia and Denmark, which have different levels of assistance based on employment status according to OECD statistic – in these cases it was the data for the ‘Employed’ SA level that were included; and 2) the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, which have no scheme comparable to SA.

[2] https://basicincome.org/bien/pdf/munich2012/Korosec.pdf

[3] https://let.azurewebsites.net/upload/tanulmany.pdf (English version unavailable).

[4] https://basicincome.org/news/2015/12/finland-basic-income-experiment-what-we-know/

[5] https://basicincome-europe.org/ubie/charter-ubie/

[6] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-swiss-pay-idUSBRE9930O620131004

[7] Alexander de Roo, by mail.