by Andre Coelho | Feb 1, 2018 | News

The London School of Economics (LSE) will host a Basic Income day event on Tuesday, 20th of February 2018.

This event will join several experts to discuss political feasibility, funding mechanisms and costing of basic income, in the morning session. On the afternoon, a roundtable will take place, featuring representatives of several basic income pilot projects and experiments worldwide. Among these pilot projects, findings from the Namibia, India and Kenya cases will be discussed, as well as analysis from the US and Canadian experiments in the 1970s. Other initiatives, ongoing or in preparation, will also be referred, such as in the Netherlands and Scotland.

A wide range of academics, researchers, activists and officials (namely from the United Nations Development Programme) will be present, such as Hartley Dean, Anne Miller, Sarath Davala, Evelyn Forget, Olli Kangas and Michael Cooke, to name a few.

Information and registration can be accessed at the event’s webpage.

More information at:

Citizen’s Income Trust Newsletter, January 2018

by Faun Rice | Jan 26, 2018 | News

In a July 2017 televised Town Hall with KCET, Economic Security Project co-chairs Chris Hughes and Natalie Foster were asked about the principles of a Universal Basic Income. Public questions from Facebook were delivered by the moderator, the first common concern of which was: should we “give everybody a Basic Income,” even the lazy and wealthy?

Foster took the question and responded with a “yes,” commenting that a universal policy “had more political resiliency” (programs with universal access would attract more support), and that shifting economic situations for the American middle class suggested that support for everyone was logical. She clarified that a Basic Income, whatever the size, is intended to be delivered to everyone with “no strings attached.”

Hughes followed up during a second question on the affordability of Basic Income. He commented that a program could be made more affordable by starting small and scaling up, by, for example, beginning with small monthly payments of $200 to American adults (not quite universal, but not means tested), between the ages of 18 and 64, placing the brunt of the tax burden for this measure on wealthy Americans or in a carbon tax. Hughes also compared Basic Income’s feasibility to existing social security programs.

More recently, Hughes’ new book, Fair Shot: Rethinking Inequality and How We Earn (February 2018), will propose a guaranteed income of $500 per month for working adults whose households earn less than $50,000 annually, with the same provided for students and unpaid caregivers.

Hughes’ book is promoted by but independent of the Economic Security Project, “a network committed to advancing the debate on unconditional cash and basic income in the United States.” Their purview includes, but is not limited to, a Universal Basic Income (UBI), as defined by BIEN: “a periodic cash payment unconditionally delivered to all on an individual basis, without means-test or work requirement.”

Chris Hughes. Credit to: SpeakerHub

The version of guaranteed income that Hughes promotes is very different from that espoused by others at ESP, such as senior fellow Andy Stern, whose 2016 book Raising The Floor makes a case for UBI, because a test based on household income and employment is not the same as giving every individual an unconditional Basic Income. Ongoing coverage of guaranteed income experiments has shown that many governments and organizations follow the same trend as Hughes, pursuing studies that offer cash payments that are means-tested, based on employment status, or revoked when income or employment status exceed minimum limits. Several Dutch experiments encountered obstacles to implementing a UBI pilot not just in public opinion but also in federal compliance issues. UBI proponents may face pressure to give money only to the worthy, and to define that worthiness socioeconomically.

The idea that a guaranteed income is best directed at the poor (and more specifically the working poor) is reiterated in Hughes’ press release email for Fair Shot:

As I write in the book, I’m the first to recognize how lucky I got early in life, but I’ve come to believe this luck doesn’t come from nowhere. We’ve created an economy that creates a small set of fortunate one percenters while making it harder and harder for poor and middle-class people to make ends meet. But we also have a proven tool to beat back against economic injustice—recurring cash payments, directly to the people who need them most. A guaranteed income for working people would provide financial security to all Americans and lift 20 million people out of poverty overnight. It would cost less than half of what we spend on defense a year.

The question raised by the KCET Facebook commentators about ESP’s proposal to give money to “everyone” reflects the same ongoing public concerns that some have about welfare and social programs. It asks for beneficiaries to prove that they are worthy in order to receive public money, and it raises the suspicion that recipients will be lazy or will not attempt to re-enter the workforce. Hughes’ new message in Fair Shot attempts to counteract this by arguing that the beneficiaries are worthy: they are employed, hard working, and “need it most.” He thus reassures the reader that the recipients are deserving.

In contrast, the answer given by Foster in the July 2017 town hall promoted a “no strings attached” UBI. The Economic Security project and associated individuals encourage research and debate around Basic Income and guaranteed incomes; the parameters of upcoming affiliated projects like the Stockton Demonstration (yet to be fully released at this time) suggest an interest both in UBI and in guaranteed income systems.

More information at:

KCET Facebook feed, ‘Town Hall Los Angeles: Q&A with Chris Hughes and Natalie Foster’, KCET Broadcast and Media Production Company, 26th July 2017

Chris Hughes , ‘Fair Shot: Rethinking Inequality and How We Earn’, FairShotBook.com (‘Amazon Review: Fair Shot: Rethinking Inequality and How We Earn’, Amazon.com)

‘Kirkus Review’, KirkusReviews.com, 24th December 2017

Kate McFarland, ‘NEW BOOK: Raising the Floor by Andy Stern’, Basic Income News, 11th June 2016

Andy Stern, ‘Moving towards a universal basic income’, The World Bank.org Jobs and Development Blog, 4th December 2016

Kate McFarland, ‘Overview of Current Basic Income Related Experiments (October 2017)’, Basic Income News, 19th October 2017

by Micah Kaats | Jan 16, 2018 | News

As many as 375 million people may have to switch jobs as a result of automation by 2030. This is according to a new report published by the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), a private sector think tank and the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company.

According to MGI researchers, “the transitions will be very challenging – matching or even exceeding the scale of shifts of agriculture and manufacturing we have seen in the past.” Such dramatic shifts in the global labor market will demand proportionately dramatic responses from governments, businesses, and individuals. Specifically, the MGI report emphasizes the importance of providing transition and income support to workers.

The report, entitled “Jobs Lost, Jobs Gained: Workforce Transitions in a Time of Automation”, builds on previous MGI research suggesting that 50% of global work activities could theoretically be automated by modifying existing technologies. While only 5% of jobs are at risk of disappearing entirely, 6 in 10 of jobs have 30% of constituent work activities that could be automated. According to MGI researchers, the question is not whether or not automation will alter the nature of work, but how long it will take.

Their analysis model potential net employment changes over 12 years for more than 800 occupations in 46 countries, focusing particularly on China, Germany, India, Japan, Mexico, and the USA. The report also accounts for several factors that could affect the pace of automation including technological and financial feasibility, demographic changes to labor markets, wage dynamics, regulatory responses, and social acceptance.

The report finds that 75 million to 375 million workers, or 3 – 14% of the global workforce, may be displaced by automation by 2030. These effects will be particularly felt in high income countries. In the most extreme scenario, 32% of American workers (166 million people), 33% of German workers (59 million people), and 46% of Japanese workers (37 million people) will be forced out of their jobs by 2030.

However, there may not be any shortage of new jobs available. MGI’s researchers note that new jobs will need to be created to care for aging societies, raise energy efficiency, address challenges posed by climate change, provide goods and services to the growing global middle class, and build new infrastructure.

Automation itself may also have the potential to create at least as many jobs as it destroys. Historically, transformative technological advancements have often led to significant jobs growth across industries.

The real challenge will be to ensure a smooth and stable transition between jobs. According to MGI research, automation is likely to disproportionately affect workers over 40, and sustained investments in retraining programs will be necessary to prepare midcareer workers for new employment opportunities. The report notes that this will require “an initiative on the scale of the Marshall Plan…involving collaboration between the public and private sectors.”

The MGI researchers also emphasize the need for increased financial support during transitions. Workers will need unemployment insurance to compensate for lost wages, as well as supplemental income to offset wage depressions typical in transitioning economies. A universal basic income (UBI) may be capable of satisfying both needs.

The report points to completed UBI trials in Canada and India, which showed no significant reduction in work hours and demonstrated increases in quality of life, healthcare, parental leave, entrepreneurialism, education, and female empowerment. The report also references ongoing and planned UBI experiments in the United States, Uganda, Kenya, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands as programs to watch in the years to come.

The worldwide spread of automation may be inevitable, but according to researchers at the McKinsey Global Institute, the demise of human labor is not. Whether or not we can respond effectively to the needs of a changing economy will depend largely on our ability to ensure a secure and stable transition for displaced workers.

More information at:

James Manyika, Susan Lund, Michael Chui, Jacques Bughin, Jonathan Woetzel, Parul Batra, Ryan Ko, and Saurabh Sanghvi, “What the future of work will mean for jobs, skills, and wages”, McKinsey Global Institute, November 2017

by Guest Contributor | Dec 4, 2017 | News

A new report from the International Labour Office (ILO), a United Nations agency dealing with labour-related issues, mentions Basic Income as an option for the reform of social security:

… is a renewed debate about a universal basic income (UBI) as a way of improving income security in the face of uncertain availability of jobs. As argued by proponents, it would guarantee a minimum standard of living for everyone irrespective of employment, age and gender, and would give people the freedom and space to live the life they want. Its proponents also argue that a UBI may contribute to alleviating poverty while reducing the administrative complexity and cost of existing social protection systems. A wide range of proposals are being discussed under the label of UBI, highly divergent in terms of objectives, proposed benefit levels, financing mechanisms and other features. Opponents of UBI proposals dispute its economic, political and social feasibility, question its capacity to address the structural causes of poverty and inequality, and fear that it may entail disincentives to work. Moreover, it is argued that a UBI – especially neoliberal or libertarian UBI proposals that aim at abolishing the welfare state – may increase poverty and inequality and undermine labour market institutions such as collective bargaining. (p.180)

To read the whole report, click here.

Photo: “Unemployment line” at FDR Memorial, CC BY 2.0 woodleywonderworks

by Karl Widerquist | Nov 26, 2017 | Opinion, The Indepentarian

This post is one of several previewing the book I’m writing on Universal Basic Income (UBI) experiments, and it is the second of two reviewing the five Negative Income Tax (NIT) experiments conducted by the U.S. and Canadian Government in the 1970s. This post draws heavily on my earlier work, “A Failure to Communicate: What (if anything) Can We Learn from the Negative Income Tax Experiments.”

Last week I argued that the results from the NIT experiments for various quality-of-life indicators were substantial and encouraging and that the labor-market effects implied that the policy was affordable. As promising as the results were to the researchers involved the NIT experiments, they were seriously misunderstood in the public discussion at the time. But the discussion in Congress and in the popular media displayed little understanding of the complexity. The results were spun or misunderstood and used in simplistic arguments to reject NIT or any form of guaranteed income offhand.

The experiments were of most interest to Congress and the media during the period from 1970 to 1972, when President Nixon’s Family Assistance Plan (FAP), which had some elements of an NIT, was under debate in Congress. None of the experiments were ready to release final reports at the time. Congress insisted researchers produce some kind of preliminary report, and then members of Congress criticized the report for being “premature,” which was just what the researchers had initially warned.[i]

Results of the fourth and largest experiment, SIME/DIME, were released while Congress was debating a policy proposed by President Carter, which had already moved quite a way from the NIT model. Dozens of technical reports with large amounts of data were simplified down to two statements: It decreased work effort and it supposedly increased divorce. The smallness of the work disincentive effect hardly drew any attention. Although researchers going into the experiments agreed that there would be some work disincentive effect and were pleased to find it was small enough to make the program affordable, many members of Congress and popular media commentators acted as if the mere existence of a work disincentive effect was enough to disqualify the program. The public discussion displayed little, if any, understanding that the 5%-to-7.9% difference between the control and experimental groups is not a prediction of the national response. Nonacademic articles reviewed by one of the authors[ii] showed little or no understanding that the response was expected to be much smaller as a percentage of the entire population, that it could potentially be counteracted by the availability of good jobs, or that it could be the first step necessary for workers to command higher wages and better working conditions.

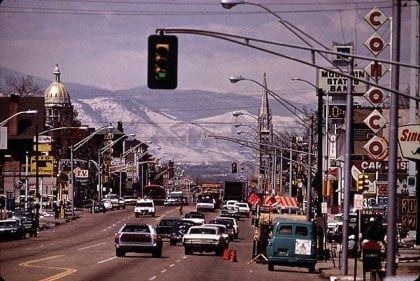

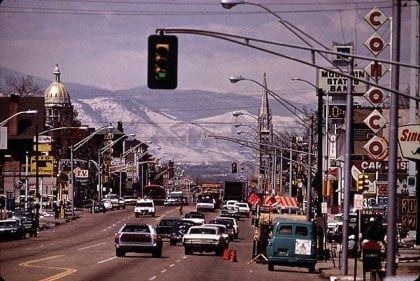

The United Press International simply got the facts wrong, saying that the SIME/DIME study showed that “adults might abandon efforts to find work.” The UPI apparently did not understand the difference between increasing search time and completely abandoning the labor market. The Rocky Mountain News claimed that the NIT “saps the recipients’ desire to work.” The Seattle Times presented a relatively well-rounded understanding of the results, but despite this, simply concluded that the existence of a decline in work effort was enough to “cast doubt” on the plan. Others went even farther, saying that the existence of a work disincentive effect was enough to declare the experiments a failure. Headlines such as “Income Plan Linked to Less Work” and “Guaranteed Income Against Work Ethic” appeared in newspapers following the hearings. Only a few exceptions such as Carl Rowan for the Washington Star (1978) considered that it might be acceptable for people working in bad jobs to work less, but he could not figure out why the government would spend so much money to find out whether people work less when you pay them to stay home.[iii]

Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who was one of the few social scientists in the Senate, wrote, “But were we wrong about a guaranteed income! Seemingly it is calamitous. It increases family dissolution by some 70 percent, decreases work, etc. Such is now the state of the science, and it seems to me we are honor bound to abide by it for the moment.” Senator Bill Armstrong of Colorado, mentioning only the existence of a work-disincentive effect, declared the NIT, “An acknowledged failure,” writing, “Let’s admit it, learn from it, and move on.”[iv]

Robert Spiegelman, one of the directors of SIME/DIME, defended the experiments, writing that they provided much-needed cost estimates that demonstrated the feasibility of the NIT. He said that the decline in work effort was not dramatic, and could not understand why so many commentators drew such different conclusions than the experimenters. Gary Burtless (1986) remarked, “Policymakers and policy analysts … seem far more impressed by our certainty that the effective price of redistribution is positive than they are by the equally persuasive evidence that the price is small.”[v]

This public discussion certainly displayed “a failure to communicate.” The experiments produced a great deal of useful evidence, but for by-far the greatest part, it failed to raise the level of debate either in Congress or in public forums. The literature review reveals neither supporter nor opponents who appeared to have a better understanding of the likely effects of the NIT and UBI in the discussions following the release of the results of the experiments in the 1970s.[vi]

Whatever the causes for it, an environment with a low understanding of complexity is highly vulnerable to spin with simplistic if nearly vacuous interpretation. All sides spin, but in the late 1970s NIT debate, only one side showed up. The guaranteed income movement that had been so active in the United States at the beginning of the decade had declined to the point that it was able to provide little or no counter-spin to the enormously negative discussion of the experimental results in the popular media.

Whether the low information content of the discussion in the media resulted more from spin, sensationalism, or honest misunderstanding is hard to determine. But whatever the reasons, the low-information discussion of the experimental results put the NIT (and, in hindsight, UBI by proxy) in an extremely unfavorable light, when the scientific results were mixed-to-favorable.

The scientists who presented the data are not entirely to blame for this misunderstanding. Neither can all of it be blamed on spin, sound bites, sensationalism, conscious desire to make an oversimplified judgment, or the failure of reports to do their homework. Nor can all of it be blamed on the people involved in political debates not paying sufficient attention. It is inherently easier to understand an oversimplification than it is to understand the genuine complexity that scientific research usually involves no matter how painstakingly it is presented. It may be impossible to communicate the complexities to most nonspecialists readers in the time a reasonable person to devote to the issue.

Nevertheless, everyone needs to try to do better next time. And we can do better. Results from experiments in conducted in Namibia and India in the early 2010s and late ’00s were much better understood, as resulted from Canada’s Mincome experiment that sadly did not come out until more than two decades after that experiment was concluded.

The book I’m working on is an effort to help reduce misunderstandings with future experiments. It is aimed at a wide audience because it focuses the problem of communication from specialists to non-specialists. I hope to help researchers involved in current and future experiments design and report their findings in ways that are more likely to raise the level of debate; to help researchers not involved in the experiments raise the level of discussion when they write about the findings of the experiment, to help journalists understand and report experimental findings more accurately; and to help interested citizens of all political predispositions see beyond any possible spin and media misinterpretations to the complexities of the results of this next round of experiments—whatever they turn out to be.

[i] Widerquist, 2005.

[ii] Widerquist, 2005.

[iii] Widerquist, 2005.

[iv] Widerquist, 2005.

[v] Burtless, 1986.

[vi] Widerquist, 2005.