by Guest Contributor | May 3, 2023 | Events, News

Jamesta Istimewa is a Basic Income Pilot experiment that provides participants free cash payments without strings attached. “Jamesta” means Universal Basic Income Guarantee in Bahasa (Indonesian language), and “Istimewa” means “special,” which is nothing but another name for the Special Region of Yogyakarta. In this place, this experiment was conducted. Jamesta Istimewa also has the privilege of being the first Crowdfunding-Based Basic Income Pilot experiment in Yogyakarta and Indonesia, which was carried out in a structured and systematic manner.

Yogyakarta’s Basic Income Pilot (YBIP) was conducted to answer some basic questions: Do people tend to be lazy when receiving free money? Is that true, or is it just a myth? Can Basic Income – to a certain extent – positively affect a person’s mental health? How do Basic Income recipients interpret and respond to Basic Income payments for themselves and their future? As well as various other interesting questions that have been coloring the debates related to the pros and cons of UBI, especially in the Indonesian context.

This Basic Income Pilot ran from November 2021 to April 2022. Experimental participants were recruited through an online open form distributed to the public in Yogyakarta. This city was chosen because it has a unique and interesting sociodemographic characteristic. Yogyakarta is widely known as a college-student-friendly city. With hundreds of universities, students come here from all over Indonesia. Yogyakarta is also known as a city of arts and culture with various relics of the past, which attracts millions of tourists from all over the world every year. Yogyakarta is also known as an area with a relatively low minimum wage level compared to other provinces in Indonesia. Furthermore, the cost of living in Yogyakarta is also touted as one of the cheapest in the country. Of course, the attributions above are debatable. But Yogyakarta’s unique sociocultural and socioeconomic setting was considered appropriate and exciting for carrying out this first Basic Income experiment in Indonesia.

Anyone living within the province of Yogyakarta during the experimental period (November 2021-April 2022) could register as a participant. Yogyakarta consists of four regencies (Sleman, Bantul, Kulon Progo, and Gunung Kidul) and one city (Yogyakarta City). According to the results of the 2020 Population Census (BPS, September 2020), the total population of DIY was 3,668,719 people. Participants who lived in Yogyakarta did not have to have a Yogyakarta ID card. Those who had a Yogyakarta ID card but lived outside Yogyakarta at the time of the experiment could not register as participants. When registration opened online on October 15, 2021, there were 2150 initial registrants. It was found that 50 double registrants had to be removed. Thus, the total number of registrants for this experiment was 2,100 people spread across five DIY regions. The average age of applicants was 33 years, with a composition of 51.4 percent male and 48.1 percent female. Of a hundred Pilot participants, 60 percent of them are female.

From the 2,100 registrants, 100 participants were randomly selected to be involved in further experiments: 25 recipients of basic income (control group) and 75 people who did not receive basic income but were willing to be involved and fill out the questionnaire given by the researcher (control group). The drawing process was carried out via Livestream on YouTube, and the recording can be seen here.

Jamesta Istimewa was run by a group of enthusiastic volunteer-young people in Yogyakarta. Most of them live in Yogyakarta, and some work remotely from outside the city, for example in Bandung and Jakarta. This experiment ran because of the full support of the CEOs of Kita Bisa (M. Al Fatih Timur) and M. Faiz Ghifari (Strategic Initiatives Kitabisa.com). Sena M. Luphdika was the project coordinator responsible for the overall management and implementation of this Pilot. Sena was supported by several other volunteers, such as Bimo Ario Suryandaru (Campaign Coordinator), Dianti Wulansari, Kurniawan Adhi, and Niko Febrianur (Webmaster). They are the ones who were behind the scenes running this Pilot from beginning to end. Yanu Endar Prasetyo (IndoBIG Network & Research Center for Population BRIN) is the research coordinator responsible for the study of this Pilot.

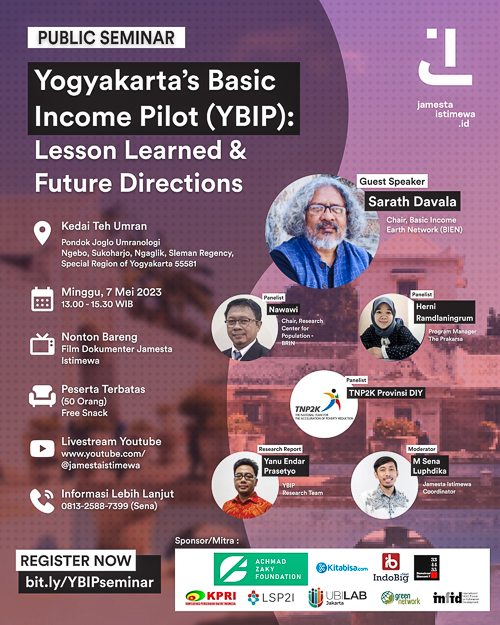

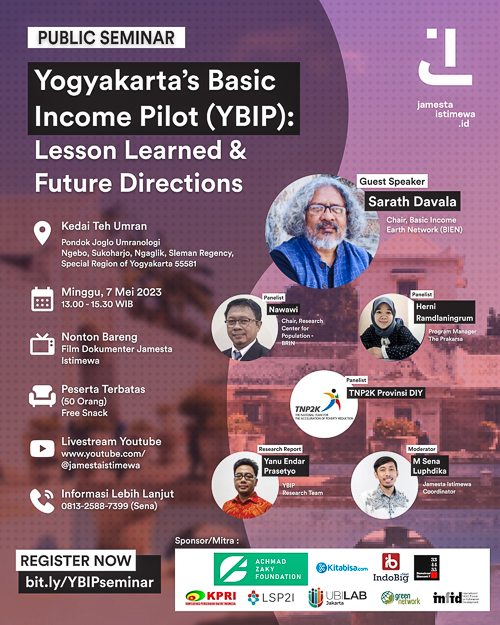

The final report of this pilot experiment will be released on Sunday, May 7, 2023 in a public discussion in Yogyakarta with some panelists such as Sarath Davala (Chair, BIEN), Dr. Nawawi (Chair, Research Center for Population – BRIN), Herni Ramdlaningrum (The Prakarsa) and representatives from the Yogyakarta Province Poverty Reduction Acceleration Team. The discussion also can be followed on YouTube Live Stream by clicking here.

by Peter Knight | Mar 5, 2023 | News

Illustration above by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters; iStock

“State and local governments, and some private funders, are launching dozens of pilot projects making direct, monthly payments to low-income residents to help meet basic needs. Researchers will study what happens next. Key question: will this money add to, reform, or supplant current welfare programs?

Four years after Stockton conducted a nationally-watched experiment, giving 125 households $500 a month with no strings attached, dozens of programs throughout California are testing the idea of a guaranteed income.

CalMatters identified more than 40 similar pilot programs that have run, are operating or are planning to launch around the state. They are sending certain groups of low-income people regular, unrestricted cash payments ranging from $300 to $1,800 a month for periods of six months to three years, depending on the program.”

Read more and search a database of the California pilots here.

by Peter Knight | Feb 13, 2023 | News

An article in the New York Times published February 13 states that “For recipients, it’s a lifeline. For liberal supporters, it shows how expanding government can make a difference. For conservatives, it’s a return to wasteful welfare handouts.”

“Chicago and the surrounding suburbs of Cook County are conducting the largest experiment of its kind in the nation, an effort to supply thousands of residents with a basic level of subsistence, not in the form of food, housing or child care — just cash. Ms. Lightfoot’s $31.5 million Resilient Communities Pilot selected 5,000 city residents in August to receive a guaranteed cash income for a year. The first $500 checks from a separate program, a $42 million county pilot, went out in December to 3,250 residents concentrated in the near-in Chicago suburbs.”

Read the full article here.

by Guest Contributor | Apr 11, 2021 | Featured, News, Research

Editor’s note: The use of the term ‘basic income’ for the sheme in Janggo Island does not correspond to BIEN’s definition of basic income, since it is paid not to all residents but to only participants in communal fish farming activities for 20 years, and paid not to individual but to household.

A forum took place on the meaning and issues of the basic rural income social experiment, which Gyeonggi Province plans to conduct in the second half of this year. Entitled, “The Meaning and Issues of the Community-centered Basic Income Social Experiment,” the first Rural Basic Income Policy Forum was held on the 29th of January and introduced cases and discussed India’s basic income experiment, distribution of shared assets in Boryeong, Chungcheongnam-do, and Jeju Island. The Hankyoreh Economic and Social Research Institute with the Gyeonggi-do Agricultural and Fisheries Promotion Agency, the Basic Income Korea Network, Lab 2050, the Korea University Institute of Government Studies, and the Korea Regional Development Foundation all participated in organizing the January event. Some of the presenters and debaters participated online.

Lessons from the Indian basic income experiment

Sarath Davala, the keynote speaker, is the architect of India’s basic income social experiment and chairman of the Basic Income District Network, which leads the discussion on basic income worldwide. He laid out the implications of basic income experiments conducted in India and Namibia.

Namibia and India conducted basic income experiments—in 2008 and 2011, respectively—during which Namibia paid USD 12 and India USD 4 per month to 2,000 people for a span of 12 months. “Contrary to many people’s expectations, people who received basic income did not become lazy. Start-ups and economic activity increased, new transportation facilities were opened, school attendance rates rose, household debt decreased, and other good things occurred. In Namibia, the consumption of alcohol remained unchanged,” Dr. Davala explained.

Dr. Davala also introduced changes in policies following basic income social experiments. “After the social experiment, the local government in India began providing cash allowances to all farmers proportional to their farmland area in 2018, and through this policy, the party won three-quarters of the local council. […] However, the program excluded sharecroppers and non-farmers and allowances were paid only to owners of land in rural areas, and basic income discussions focused mainly on ‘the excluded.’ […] The implications of the Indian outcomes on other basic income experiments is that one needs to follow the principle of individuality and avoid excluding anyone in the region.”

Dr. Davala emphasized the role of social experimentation in promoting social dialogue beyond the collection of evidence. “In the past, we did not conduct small-scale social experiments in advance before abolishing slavery or winning women’s suffrage. These policies were based on values, philosophy, and human rights. Obviously, the policy effect rationale is important, but the policy is not implemented only with evidence. In India, political movements took place after social experiments, and there was a close review and public discussion of what was better,” he said. Another aspect of the social experiment he emphasizes is that it triggered dialogue between the public and the media, experts, and political parties to discuss desirable alternatives. “In Korea, there have been experiments with things such as youth dividends in Seongnam City, a basic income for young people in Gyeonggi Province, and national disaster support funds amid the Corona crisis, which has attracted the attention of politicians and the public.”

Sea cucumber seeds become basic income for islanders

The forum also presented a case where a local community shares the profits generated from a shared asset. Kang Je-yoon, head of the Island Research Institute, explained how Janggo Island allocates the profits from collected seafood to the islanders. Janggo is a small island with 81 households and 200 residents and began allocating profits from sea cucumber farming grounds in 1993. In 2019, 11 million won (around USD 10,000) was paid annually to each household in basic income. Kang said, “Unlike other fisheries, sea cucumbers grow on their own when the residents sow seeds. There is nothing residents have to do with them until they are ready for harvesting. Residents of Janggo Island receive a basic income from sea cucumber farming, which requires minimal labor, and the same amount is allocated as labor income from collecting clams ten times over two months. “Since the village community provides a basic income and labor income together worth 20 million won per year (USD 19,000), Janggo Island residents earn equal and stable income, unlike residents of other islands, where large income gaps exist between those in the aquaculture industry and those who are not.

However, Janggo Island also went through a slow and painful process before residents received a consistent dividend. Initially, the fishing village fraternity rented out fishing grounds around Janggo Island to fish farmers, who paid rent to the village society. Director Kang said, “It is illegal to rent out fishing grounds, which no one owns, and beside that, the rent was 500,000 won a year, which was an absurdly low price for 1983. In 1983, the village’s newly appointed head persuaded residents to reclaim the fishing grounds, after which they managed the profits from the fishing grounds (now village property) for ten years, and gave out loans. After much controversy, the dividend first began in 1993, and residents’ complaints about fishing grounds profits subsided, and the community’s common interest in the fishing grounds increased the quality of management.” A fair distribution system supported the management of shared assets.

Kim Ja-kyung, an academic research professor at Jeju National University, who presented on the possibility of basic income through shared assets on Jeju Island, said, “Jeju Island has a tradition of distributing profits through communal operation of pastureland and fisheries. For example, one village harvests seaweed fusiforme and agar together and distributes them among the participants while allowing individuals to keep the collected seaweed for themselves. One hundred and one fishing village fraternities had their own unique customs and order.”

Recently, wind and wind power generation has been drawing greater attention as a new shared asset on Jeju. Professor Kim gave a wind farm in Haengwon-ri, Gujwa-eup, eastern Jeju Island as an example. “Six villages in Haengwon-ri receive part of their wind power generation profits and set aside the funds. […] There is always a possibility of conflict and disagreement in the village, which prevents certain people from arbitrarily exercising their decision-making authority.” There is still work left to be done to develop a system to distribute the new shared asset profits fairly.

Consideration of the impact of distribution system on residents

Lee Chang-han, director of the Korea Regional Development Foundation, which designed the basic income social experiment in rural areas in Gyeonggi Province, said the experiment’s primary purpose is to closely examine the impact of basic income on the local community. “Because of the name “basic rural income,” many people are confused whether it only benefits farmers. However, farmers in rural areas in Gyeonggi-do Province make up only about 16% of the total population. It is crucial how farmers and non-farmers interact in the same living space in these rural areas. Like Janggo Island, we will observe the impact of the distribution system on resident communities.”

Park Kyung-chul, a researcher at Chungnam Research Institute, said, “Since 2019, various local governments have introduced farmers’ allowances, and there has been a discussion on farmers’ basic income. […] However, since non-farmers are also, directly and indirectly, involved in agricultural activities in rural areas, and together they form local communities, expanding the scope of payments to all rural residents is the concept behind basic income.”

Lee Ji-eun, CEO of the Basic Income New Research Network, said, “The basic income social experiment in rural areas can be reevaluated in terms of climate justice.” She added, “We hope this experiment will lead to discussions on rediscovering ‘the commons’ (shared assets), discovering small sustainable economic models and revitalizing ecological feminism, reflecting the peculiarity of rural areas.”

Lee Won-jae, CEO of Lab2050, who headed the debate, said, “I think the basic income social experiment in Gyeonggi Province has a unique status, as does the basic income experiment in Finland…where the prime minister in power conducted a policy experiment. In Korea, the experiment is taking place when basic income is becoming a central political topic.” This means that it is an environment in which the country’s overall policy will follow the results of the social experiment.

For more information, check out Gyeonggi Rural Basic Income Social Experiment’s blog page: https://gg-rbip.medium.com/

Written by Yoon Hyeong-joong, visiting fellow at the Hankyoreh Economy and Society Research Institute, philyoon23@gmail.com

Translated by Eunjae Shin, researcher at the Hankyoreh Economy and Society Research Institute, eunjae.shin@hani.co.kr Reviewed by Toru Yamamori, Academic Research Editor of BIEN

Photo: Credit: Janggo Island, South Korea, is experimenting on sharing dividends from sea cucumber farming grounds with its residents. Provided by Kang Je-yoon.