by Karl Widerquist | Dec 24, 2017 | Opinion, The Indepentarian

This audio is of talk I gave on why we need a Universal Basic Income. I gave the talk for the “Sydney Ideas” series in August of 2017, and I’m particularly happy with it. It summarizes the reasons I think are most important, and I think I did a relatively good job of delivering it. It discusses how Basic Income removes the judgment and paternalism that pervade the world’s existing social welfare systems, and why doing so is so important not only for people at the bottom but also for the average worker. It also briefly addresses how to craft a realistic Basic Income proposal, how much it costs, options for paying for it, and evidence about what it can do.

Following the lecture the audio file includes a question and answer session where I’m joined by Dr Elizabeth Hill, Chair of Department of Political Economy, School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Sydney, and Professor Gabrielle Meagher, Department of Sociology, Macquarie University.

by Micah Kaats | Dec 24, 2017 | News, Research

In the three years since its initial publication, Rutger Bregman’s Utopia for Realists has helped spur a global conversation on universal basic income (UBI). The book has become an international bestseller, garnering praise from intellectual heavyweights and propelling its author to the TED stage this past April. However, Stephen Davies, education director at the Institute for Economic Affairs (IEA), remains skeptical of many of the young Dutch journalist’s ideas. He makes his case in the most recent edition of the Journal of Economic Affairs.

“Rutger Bregman’s book is both interesting and irritating,” declares Davies in the opening line of his review. To clarify, he quickly notes that it is interesting “not so much because of its particular content…but because it gives us an insight into what may turn out to be a development of both intellectual and political importance” (p. 442). Such an off hand rejection of a book advocating basic income from the education director of a think tank advocating free market capitalism may be unsurprising to some, but Davies’ response is actually not as inevitable as it may seem. Historically, UBI has found supporters on both sides of the political divide.

Davies distinguishes between two types of arguments Bregman makes for basic income. The first considers UBI to be a pragmatic solution to the shortcomings of the current social welfare system. The second considers it to be a necessary means of radically transforming the existing social order. While Davies may be more sympathetic to the second line of reasoning, he spends most of his time critiquing the first.

Steven Davies. Credit to: The London School of Economics and Political Science

In Utopia, Bregman draws on a wealth of research to highlight deficiencies in the means-tested benefit programs that constitute the welfare states of most developed societies. He notes that many of these programs create negative incentives, keeping beneficiaries locked in a poverty trap. Even worse, financial instability can result in a scarcity mindset, making it even harder for poor people to make responsible financial decisions. According to Bregman, unconditional cash transfer programs (UCTs) have proven to be the most successful remedy to this vicious cycle of poverty and dependence. In support of this view, Bregman offers additional in-depth analyses of related programs, including Richard Nixon’s Family Assistance Plan, negative income taxes, and the Speenhamland system.

Davies acknowledges the implications of this body of research. He writes, “Much of the evidence presented by Bregman is indeed very striking and should encourage us simply to trust people more and have greater confidence in their judgment and their knowledge” (p. 447). However, he is far more hesitant to interpret these results as evidence for universal basic income.

Davies notes that many of the policies Bregman touches on are in fact means-tested in one way or another, and may therefore be more analogous to standard welfare programs than basic income. Additionally, Davies argues that many of the UCT programs discussed in Utopia for Realists have not been around long enough to show lasting impacts, and he calls for more research to determine the specific amounts at which UCTs can begin to induce behavioral change. Yet, even more worrisome for Davies is the “bold assumption that there is no meaningful distinction between single lump-sum payments and continuing income stream” (p. 448). He notes that while individual cash transfers may bring sudden and liberating benefits, similar effects of ongoing basic income payments may become muted over time.

According to Davies, all of this “reveals confusion over what a UBI is thought of as being – is it a way of establishing a floor or minimum that is guaranteed to all or is it a redistributive mechanism designed to narrow income differentials?” (p. 449). This confusion motivates Davies’ second critique of Bregman’s argument for universal basic income as a response to the widening global wealth gap. While basic income programs may go a long way in ensuring no one lives in a state of absolute poverty, Davies writes that “it is not clear how a UBI by itself will do anything to reduce relative poverty or inequality” (p. 449). In fact, he notes it may even make the problem of inequality worse if UBI programs seek to replace other means-tested benefits.

However, while Davies takes issue with many of Bregman’s pragmatic arguments, he seems much more sympathetic to the idealistic aspects of his account. As automation increases and “bullshit jobs” proliferate, Davies grants Bregman his assumption that UBI could become a useful tool to decouple meaningful activity from paid work. He writes, “This is clearly the vision that truly inspires Bregman, the utopia of his book’s title, and he would have done better to stick to this rather than muddy the waters by conflating it with more limited and pragmatic discussions of a guaranteed income in a society where wage labor is still widespread and predominant” (p. 456).

While he may be unmoved by Utopia for Realists, Davies clearly recognizes the significance of the political and intellectual movements it represents. The book’s international success seems to reflect a growing anxiety about stagnation of big ideas in the face of an increasingly unsatisfying status quo. Davies concludes, “What we are starting to see is an attempt to work out what a non-capitalist or, more accurately, a post-capitalist political economy would look like” (p. 457).

Davies review appears in the most recent edition of the Journal for Economic Affairs.

by Faun Rice | Dec 21, 2017 | Research

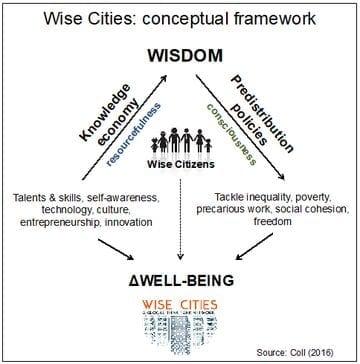

“Wise Cities & the Universal Basic Income: Facing the Challenges of Inequality, the 4th Industrial Revolution and the New Socioeconomic Paradigm” by Josep M. Coll, was published by the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB) in November 2017. CIDOB is an independent think tank in Barcelona; its primary focus is the research and analysis of international issues.

The Wise Cities Model

CIDOB has published other works about a concept it calls “Wise Cities,” a term intended to holistically encompass words like “green city” or “smart city” in popular usage. Wise Cities, as defined by CIDOB and others in the Wise Cities think tank network, are characterized by a joint focus on research and people, using new technologies to improve lives, and creating useful and trusting partnerships between citizens, government, academia, and the private sector.

The 2017 report by Coll opens with a discussion of the future of global economies; it highlights mechanization of labour, potential increases in unemployment, and financial inequality. It next points to cities as centres of both population and economic innovation and experimentation. A Wise City, the paper states, will be a hub of innovation that uses economic predistribution—where assets are equally distributed prior to government taxation and redistribution—to maximize quality of life for its citizens.

Predistribution in Europe: Pilot Projects

Universal Basic Income (UBI) is one example of a predistribution policy. After touching on UBI’s history and current popularity, Coll summarizes European projects in Finland, Utrecht, and Barcelona in order to highlight city-based predistribution experiments. Coll adds that while basic income is defined as unconditional cash payments, none of these pilots fit that definition: they all target participants who are currently, or were at some time, unemployed or low-income.

Finland’s project began in January 2017, and reduces the bureaucracy involved in social security services. It delivers an unconditional (in the sense of non-means-tested and non-work-tested after the program begins) income of 560 €/month for 2,000 randomly selected unemployed persons for two years. Eventual analysis will consist of a comparison with a larger control group of 175,000 people, and the pilot is a public initiative.

The city of Utrecht and Utrecht University designed an experiment which would also last two years, and would provide basic income of 980 €/month to participants already receiving social assistance. The evaluation would assess any change in job seeking, social activity, health and wellness, and an estimate of how much such a program would cost to implement in full. The author comments that the program was suspended by the Netherlands Ministry of Social Affairs, and the pilot is currently under negotiation.

Barcelona has begun an experiment with 1,000 adult participants in a particularly poor region of the city, who must have been social services recipients in the past. “B-Mincome” offers a graduated 400-500 €/month income depending on the household. After two years, the pilot will be assessed by examining labour market reintegration, including self-employment and education, as well as food security, health, wellbeing, social networks, and community participation. Because the income is household-based, and not paid equally to each individual, it is not a Basic Income, but the results could still provide useful evidence for the possible effects of a future Basic Income.

The Implications

Coll identifies several key takeaways from a comparison of these projects. None of the experiments assess the potential behavioural change in rich or middle class basic income recipients. In addition, multi-level governance may cause problems for basic income pilots, but these issues may be mitigated as more evidence assessing the effectiveness of UBI builds from city-driven programs. Coll also acknowledges that all of the experiments listed in his paper are from affluent regions.

In conclusion, the author argues that UBI is a necessary step to alleviate economic inequality. While cities are experimenting with the best ways to implement UBI, they are often not real UBI trials (as they are not universal), and they do not always take an individual-based approach; however, they are nevertheless useful components of the Wise City model.

More information at:

Josep M. Coll, “Why Wise Cities? Conceptual Framework,” Colección Monografı́as CIDOB, October 2016

Josep M. Coll, “Wise Cities & the Universal Basic Income: Facing the Challenges of Inequality, the 4th Industrial Revolution and the New Socioeconomic Paradigm,” Notes internacionals CIDOB no. 183, November 2017

by Pablo Yanes | Dec 19, 2017 | News

Zone 10 – Guatemala City.

With the support of the Swedish Embassy and Oxfam in Guatemala, the Central American Institute for Fiscal Studies (ICEFI) has presented a new book entitled Universal Basic Income: More Freedom, More Equality, More Jobs, More Well-being. A Proposal for Guatemala (2019-2030), was presented in simultaneous events held in Guatemala City and Quetzaltenango. The book explains how inequality is affecting people’s lives and undermining the possibilities of strengthening democracy and development in the world, and Guatemala in particular. In light of this reality, the book proposes a universal basic income (UBI) of Q175 per month (20 €/month) accompanied by increased social spending from 2019 to 2030, which could eliminate extreme poverty and reduce inequality, while generating 4.7 million jobs and potentially boosting economic growth as much as 50%. It also gives scenarios for its financing – including a progressive tax reform – and the main challenges to its effective public administration.

When studying social inequality in Guatemala, the book mentions income inequalities, worker insecurity, the scourge of child labor and lack of employment guarantees, the still unaffordable cost of the basic food basket, the acute chronic malnutrition ravaging Guatemalan children (especially indigenous and rural children), the visible discrepancies in women’s political representation in public and private power arenas, widespread poverty and extreme poverty – also more and more wearing the face of indigenous and rural women – and the complex, institutionalized racism permeating all realms of society. All this is reinforced by the overwhelming problems of corruption and lack of transparency, by paltry public spending on the production of universal, quality goods and services, and by a tax policy that lacks legitimacy among the citizenry due to the unfair way in which taxes are collected and certain economic sectors are granted privileges.

For ICEFI, this reality requires alternative proposals to help mitigate social inequality and its more harmful effects and build economic, social and fiscal scenarios for underpinning sustainable, inclusive economic development. Together with improved public goods and services, a UBI – understood as a sum of money allocated by the State to each citizen or resident – would have a positive impact on Guatemalan society. With a monthly per-person amount of Q175, the UBI could eliminate extreme poverty and reduce inequality. The study, which should be considered a seminal work subject to discussion and more in-depth examination, also reveals that a UBI such as the one proposed could generate 4.7 million jobs in the coming years (33% of the working-age population in 2030), spread out over the entire national territory in agriculture, industry, finance, and commerce – an effect that could boost economic growth by close to 50%. Moreover, the related bankarization would promote the formalizing of businesses aimed at providing goods and services to the public. Inequality would be reduced from 0.538 to 0.472, as measured on the Gini index – better than Costa Rica (0.504 in 2014) but still far from what has been recorded for Uruguay (0.379 in 2014).

As for taxes, the proposal includes financing mechanisms (with and without tax reform). The tax reform scenario is based on a modernization of the income tax, elimination of tax privileges, and gradual reduction of income and value-added tax evasion. The book also emphasizes that implementation of a public policy such as the one proposed implies a revaluation of the State’s role as the main guarantor of individual rights and booster of development and democracy. Fiscal policy can potentially close the current gap between the economy and citizen well-being. With a modern fiscal outlook and political agreement for a profound fiscal reform, the country could have the resources for financing a UBI and other public programs aimed at enhancing social well-being, smoothing the way for compliance with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development while driving productive transformation, access to credit and economic formalization.

In this book, ICEFI recognizes that a UBI would not solve all the problems the country urgently needs to face as a result of its past and present. Together with improved public services, however, it could provide a minimum though effective floor of social protection for tackling inequality and all its related phenomena. At a time when most citizens are unhappy with the current economic and political model, the study can also serve as a basis for debate on alternatives for change. Discussion of a UBI in Guatemala is expected to bring together small, medium, and large enterprises, merchants, producers and cooperatives, as well as social organizations pushing agendas for development and democracy.

The study is available in Spanish.

by Karl Widerquist | Dec 7, 2017 | Opinion, The Indepentarian

This essay was originally published in the USBIG NewsFlash in August 2005.

Jay Hammond, the governor of Alaska from 1975 to 1982, who led the fight to create the Alaska Permanent Fund, was found dead at his Homestead about 185 miles southwest of Anchorage, on Tuesday, August 2, 2005. He led an amazing life. Hammond was a laborer, a fur trapper (by dogsled), a World War II fighter pilot, an Alaskan bush pilot, a husband, a father of three, a wildlife biologist, a backwoods guide, a hunter, a fisher with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and a homesteader. Hammond was one of the last people to take advantage of the Civil-War-ear U.S. law giving away land. Other than a requirement to build a house and farm the land for five years, it was given away free—no strings attached.

Hammond was also a hero to everyone who believes that no one should be barred from the resources they need to meet their basic needs—no strings attached.

Hammond got the idea for a resource dividend when he was mayor of a small town on Bristol Bay, Alaska in the 1960s. He realized that salmon were being taken out of the area without necessarily helping the town’s poor. He proposed a three percent tax on all fish caught in the area to be redistributed to all residents of the town. By an enormous stroke of luck, the man who had that idea (and saw it work in Bristol Bay) would be elected governor of Alaska just as the state was beginning construction of the Trans-Alaska oil pipeline. Oil companies stood to make billions of dollars, and of course, they argued that Alaskans would benefit through new job opportunities, but Hammond knew one way to make sure that every single Alaskan would benefit from the pipeline.

And so the Alaskan Permanent Fund was born. For the last 20 years, every Alaskan has received income from state oil revenues. A portion of the state’s taxes on Alaskan oil goes into an investment fund, which pays dividends from the interest on those investments—hence the permanent fund. Dividends vary, but they are usually more than $1,000 per year for every man, woman, and child living in the state.

The system is not perfect. Hammond told Tim Bradner, of the Anchorage Daily News, that his biggest regret was to let the legislature eliminate the state’s income tax. Without the citizens’ responsibility to pay taxes to support state services the fund will be vulnerable, and the legislature has been trying to raid the fund ever since. So far, the enormous popularity of the fund has protected it fairly well. Hammond also regretted that the fund was too small. Only one-eighth of the state’s oil tax revenues go into the fund. If half of oil tax revenues went into the fund, as Hammond envisioned, every Alaska family of four could expect to receive more than $16,000 this year. Hammond died campaigning to increase the size of the fund.

But the most important thing about the fund is that it exists. It’s simple, it works, and everyone in the state benefits from it every year. How many elected officials can say they did that? According to Sean Butler in Dissent Magazine, Nobel Prize-winning economist Vernon Smith, called the Permanent Fund, “a model governments all over the world would be wise to copy.” It is a pilot program for resource taxes and basic income plans all over the world. Economists have recommended the Alaska solution for resource-rich, poverty-ridden countries from Nigeria to Iraq. Just this summer the government of Azerbaijan sent a delegation to Alaska to study the Permanent Fund. You can’t keep a good idea down.

Jay Hammond spoke at the 2004 USBIG Congress in Washington, DC. Here is how Butler describes the event: “The father of the Brazilian basic income, Senator Eduardo Suplicy, also presented at the USBIG conference last year. During his speech, he noticed Jay Hammond sitting in the front row, and, to warm applause from the assembled crowd, descended from the stage to shake his hand. The two basic income pioneers had at last met. Hammond and Suplicy make an odd couple. The Republican Hammond, with his Hemingway-like white beard and grizzly build, wears his far north ethos of self-reliance with pride. Suplicy, a founding member of the left-wing Brazilian Workers Party and a U.S.-trained economist, has the dignified appearance of an intellectual and professional politician. Its tropical socialism meets arctic capitalism; yet somehow, when the two come together over basic income, they get along.”

I had the good fortune to attend that event and meet Governor Hammond. He was warm and engaging. He wasn’t there to bask in the glory of people who admired his past achievements but to fight to keep improving the APF. He was a genuine hero.

An article on Hammond and basic income by Sean Butler, entitled, “Life, Liberty, and a Little Bit of Cash,’ appeared in Dissent Magazine just a few weeks before he died.

There have been many good tributes to Hammond in the news and on the internet since his death. Here are just a few:

Frank Murkowski, current governor of Alaska, “Hammond’s Legacy Will Stand Out,” Alaska Daily News

Tim Bradner, “Hammond has passed; his ideas must live on,” Alaska Daily News

Douglas Martin, “Governor of Alaska Who Paid Dividends,” New York Times