Basic Income: Remittances from Nowhere

How a World Basic Income can be sort of mostly free.

The economic downturn associated with the coronavirus is causing a humanitarian and economic disaster. Now is the time to push for a World Basic Income (WBI) paid to every human on the planet. It should be high enough to cover the cost of living, at least in the developing world. This payment would not just stave off hunger and extreme poverty, but also work as a general stimulus for the global economy, which faces a potentially catastrophic contraction.

While the greatest benefits of this payment would be felt in the developing world, where the increase in income would be bigger in proportion to their current income, it would also provide important benefits to the developed world.

A WBI would pump demand into the global economy by raising the non-wage incomes of the population as a whole, including workers. This would reshape the global labour market, lessening migration pressures and the severity of cross border wage competition, because workers in and from the developing world, protected from absolute destitution, would be less inclined to work in appalling conditions for miserable wages.

There would also be a dramatic increase in consumer spending power in developing nations, which would increase the number of workers required to meet domestic demand for goods and services, meaning fewer still would be available to work producing exports to the developed world. At the same time the market for exports from the developed world would expand.

This would compound the original effect, and further strengthen the position of workers in the US “rust belt,” and equivalent populations in other developed countries, whose jobs would become harder to send offshore.

WBI would do this without the implementation of tariffs, which might spiral into a trade war, further contracting the global economy. A WBI is a mechanism that can achieve the same goals in terms of protecting developed world jobs and wages, without adding to the contractionary pressures that the global economy faces.

A payment like this is not a new idea, it even has a dedicated NGO, simply called “World Basic Income.” They propose a payment of $30 USD a month. Which they say could be funded using “rents” on global commons like airspace, and “international taxes” such as a carbon tax.

But it is a mistake to assume that we have to first “gather up” the money before we can pay it out.

Since the pandemic began, they are also starting to question this. Having recently pondered whether in “emergency times such as these, borrowing or currency creation could also be used to quickly generate the money needed.”

This is an encouraging sign. But they still seem to be of the view that money creation or borrowing as inherently problematic, if perhaps necessary given the current situation. This is the wrong way of thinking about it. Money creation and deficit spending are not signs of desperation, foolishness, or failure. They are necessary tools for good economic management, in relatively “normal” times as well as emergencies. It is not that, as it is sometimes put, “deficits don’t matter”, it is that deficits are good. The theory behind this is a little complex but it can be summarised as it is here by Cory Doctorow:

Government debts are where our money comes from. Governments spend money into existence: if they “balance their budgets” then they tax all that money back out again. That’s why austerity always leads to economic contraction — governments are taxing away too much money.

There’s one other source of money, of course: bank loans. Banks have governments charters to loan money that they don’t actually have on hand (contrary to what you’ve been taught, banks don’t loan out their deposits).

When there’s not enough government money in circulation, people seek bank loans to fill the gap. Unlike federal debts, bank loans turn a profit for bank investors. The more austerity, the more bank loans, the more profits for the finance sector (at everyone else’s expense).

The empirical case is pretty simple, and arguably even stronger: The US government has run deficits nearly every year since the early 30s. For all its current woes, the US is in a far better economic state now than it was then. In fact, some of the best years, like the “post-war boom,” were immediately preceded by the highest levels of deficit spending (the largest injections of cash into the real economy).

The same is true for most developed economies. Governments always promise budget surpluses, but rarely deliver. And that’s a good thing, because what they practice is better than what they preach.

So when it comes to a universal basic income, even in the “good” times, the best answer to the question: “how will we pay for it?” is that we will not pay for it.

At least not all of it, not directly, and certainly not upfront. If we do pay for it upfront, we suck as much money out of the economy as we pump in.

A “costed” or “revenue neutral” UBI plan would help protect the poorest from the effects of the crisis, but it would stunt the stimulatory effect we are also aiming to achieve. There would still be some stimulatory effects. Transferring income to poorer people leads to a greater portion of that income being spent, so the velocity of money (the overall rate of spending in the economy) increases and with it GDP. But expanding supply and velocity simultaneously, as a fiat-funded UBI could, would work much better.

In essence, we should just get the money the same way we ultimately get all money: We just collectively believe it into existence. This has the advantage that it doesn’t require us to convince or compel anyone to pony up in advance. And it would mean we could pay a higher WBI, starting perhaps at $1.90 USD a day, the UN’s “internationally agreed poverty line” , and then, when the sky doesn’t fall, rising further, perhaps to as much as five or ten dollars a day over the course of several years or a decade.

Of course, no one can predict in advance how people, and therefore the world economy, would really respond to a payment of this level. No one knows what the ideal level for a WBI is. But there’s no reason to think it is zero.

The global charity and advocacy organisation Oxfam does not back a WBI, but does explicitly recommend a kind of fiat money creation, or something very much like it. In a recent media briefing entitled Dignity Not Destitution it lays out suggestions for responding to the hardship caused by the pandemic. The plan includes the allocation of a trillion dollars worth of Special Drawing Rights, which are interest-bearing assets, a bit like treasury bonds, created by the IMF. SDRs are defined in relation to five major global currencies and can be used by nations to pay back debts to the IMF, or traded with each other for liquid currency.

By rapidly increasing the supply of this “paper gold”, as they did following the 2008 financial crisis, the IMF could help nations around the world increase their liquidity, allowing them to spend money to help the needy. This has also been requested by a number of nations and the IMF has said it is “exploring” that option.

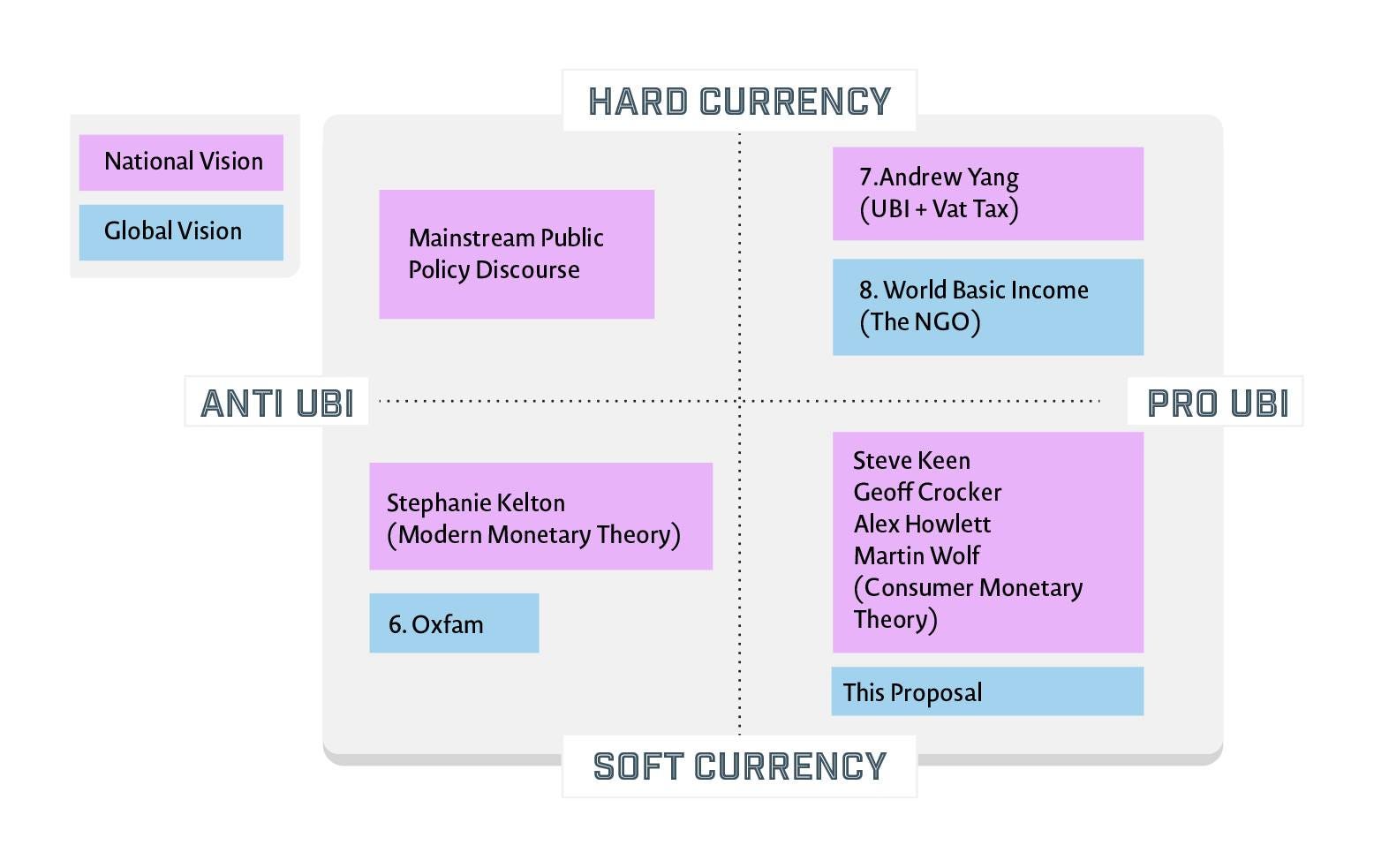

Here we see a pattern emerging at the global level which resembles closely that developing at the level of national policy discourse.

Modern Monetary Theory advocates like Stephanie Kelton argue that the US government cannot run out of money any more than a sports arena can run out of points. But they do not support UBI, arguing instead for a Federal Job Guarantee. UBI advocates like Andrew Yang want a UBI but think they need to pay for it pretty much upfront with increased tax revenues.

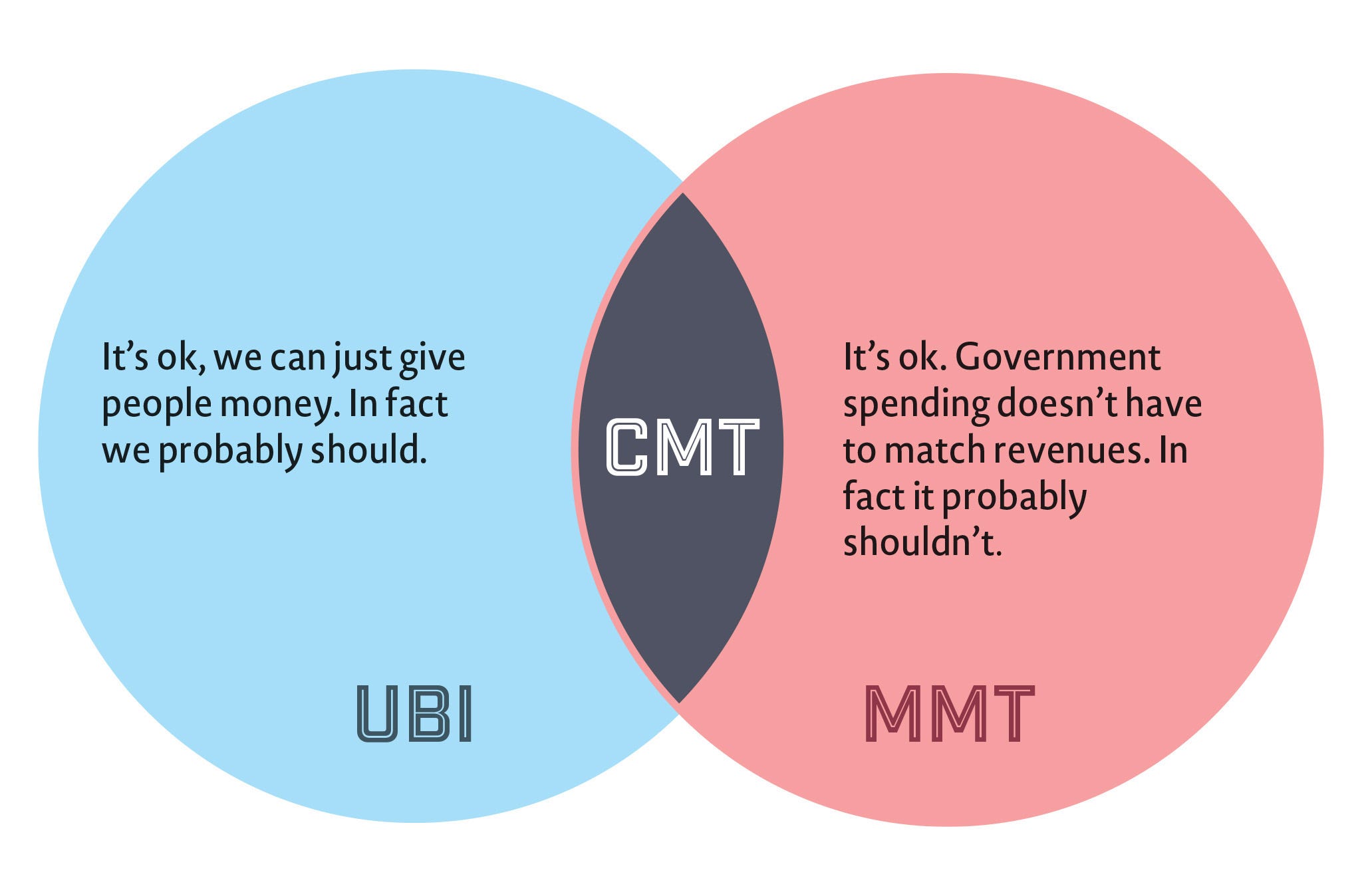

But a growing cohort of thinkers are beginning to examine what happens when these herecies intersect. UBI advocate Alex Howlett is one of them. He coined the term Consumer Monetary Theory or CMT to distinguish his view from MMT. Another is Geoff Crocker, who talks of “Basic Income and Sovereign Money”. Martin Wolf, associate editor and chief economics commentator at the Financial Times, also backs both soft money theory and a UBI, as does Australian heterodox economist Steve Keen.

The four thinkers listed in the bottom right square all have unique perspectives, and among them only Howlett identifies their work with the CMT title. However it seems useful to me as an umbrella term for those who agree with MMT regarding the nature and constraints of government spending, but who promote a Basic Income rather than a Job Guarantee.

It is important to note that both MMT and CMT do think tax policies matter, just not in the ways we are usually told they do. One role they see for taxes that is relevant to this proposal is the idea that taxes demanded by a government in a specific currency help ensure the value and widespread acceptance of that currency, another is the way taxes help manage the build-up of currency and the amount of spending in the economy to prevent inflation.

In conventional thinking, taxes fill a bucket, the “government coffers”, and spending is a hole in that bucket, through which money escapes. In soft currency thinking, spending is the inflow of money, the bucket is a flower-pot — representing the economy — which requires frequent watering. Taxes are the drainage holes, there to stop the soil getting too saturated.

If we were to look clearly at the flowerpot representing the world economy, we would see the soil is bone dry. It is worst at the edges, where the dieback has already started, but the center, where the roots are thickest and thirstiest, is not far behind. The plant is starting to wilt. The good news is that the water is free. It is time to get the hose, attach a spray nozzle, and spray.

The Great Global Monetary Hack

The world lacks a true global reserve. The US dollar is the main currency of global trade, but that role is diminishing, and in any case it is managed by a government and central bank who are only mandated to pay attention to the needs of the global economy as and when these needs affect their domestic goals.

In terms of a truly global, globally managed, reserve, SDRs are the closest thing we’ve got. We cannot use them directly for a WBI, since they can only be held by nation states and other “designated holders”. But these are considered durably credible enough that their value held in 2008, even as the total stock increased roughly 10 fold, from around $20 billion to $200 billion. The additional trillion Oxfam have recommended be created, divided by 8 billion is $125 per person, or 34 cents a day for a year. It is not enough. But we’re getting somewhere.

Since individual human beings cannot hold SDRs, which are, formally, not money. We could issue a new currency, tied to these. A People’s Bancor, in honour of Keynes’s proposed global currency.

The basic framework would be:

- The IMF announces it will be holding an auction of SDRs starting in say, three months time, and continuing at regular intervals from then onward, that these auctions will be conducted using the new currency: the People’s Bancor.

- The IMF creates digital wallets for the citizens of all participating nations and starts to issue these new digital credits (which may be cryptographically minted) at regular intervals directly to every adult individual on the planet.

- Governments exchange national currency to obtain PBs. Either directly or by accepting them as a means of (partially) paying (some) taxes. This would cause businesses, individuals and exchanges to gain confidence in the new currency.

- Governments buy SDRs from the IMF with PBs, which are then taken out of circulation.

Poorer nations, especially, could be guaranteed a certain quota at a set price, separate to the portion auctioned in batches.

Another way to validate this currency would be by charging global taxes in it.

A United Nations could create a world tax authority and through it could demand taxes in this new currency. These should be demanded, at least at first, from the national governments themselves, who would thus be compelled to buy PBs using local currency.

So long as the monetary metabolism can be kept active, substantially more can be issued in currency than is collected in taxes.

A carbon tax is, of course, an important idea. And so is a tax on military budgets, if you think about it. This is a great opportunity to go after tax havens and the many billions held there illegitimately?

We must avoid this temptation to fix everything at once, and stay focussed. The number one priority is for these global taxes to validate the currency. And we need it to happen fast. We do not have time for nations to enter into complex multilateral bargains over the rules of such a system. We need something that is equally attractive to all parties.

What I suggest is that, at least at the start, we tax the money itself. At the end of each financial year, the government could be liable for a sum of PBs equal to, for example, 20 percent of the amount received by their population over the previous 12 months.

As it happens, this stands in stark contrast to the position taken by Howlett, who as I mentioned before coined the term Consumer Monetary Theory. He says that “tax revenue is meaningless” and that we should therefore focus on taxing the specific behaviours and phenomena we want to discourage. Since we want economic activity, money is the worst thing to tax. This is a rule I generally agree with, but this is one case (and there are others) where it makes sense to make an exception.

By removing the complications implicit in attaching these initial taxes to anything in particular, we remove reasons for various countries to say no. If we view the government as an extension of the population, which it rightly should be, then all we are asking them to do is accept a dollar, on the basis they will later have to pay back 20 cents.

Imagine a simplified example where a country’s population receives 100 PBs a year in total.

Here’s how that would play out over the next twenty years:

As the graph shows, the national stock of PBs would grow over time as the amount received by the population outpaces the amount the government has paid in global taxes. So long as the rate of taxation is less than 50 percent, this will be the case.

This rate wouldn’t, obviously, be something that we could “set and forget” but would be a policy lever, similar to central bank interest rates, which could be adjusted in response to real world results. If the currency starts to lose value, the rate should be increased, if its value is too high relative to national currencies, it should be decreased.

Such an agreement would be most perfectly championed by the G20, then implemented by the IMF and UN in concert, with the IMF issuing the currency and the UN collecting (and destroying) it.

But any group of nations collectively representing a significant chunk of world product could also create their own version of this through a treaty outside existing global structures. This currency club could grow gracefully, one new member country at a time. Countries should be free to opt out at any time, making joining the obvious choice.

It would have to have a central administrative office, with dedicated staff alongside observers and advisors from member nations working to regularly assess the effectiveness of the current settings, and adjust UBI levels, taxes due, the number and type of SDR sales (assuming IMF cooperation), and so on.

Perhaps the best thing about this plan is the lack of downsides. It is, I contend, counterintuitively plausible that national governments would sign up for such a plan, especially as the economic crisis, likely to be the worst in a century, deepens.

If it does not work, then the currency will be stupidly cheap and the participant governments will easily be able to get enough to cover their obligations.

If it does work, and the value of the currency holds, then their economy is experiencing a sudden inflow of valuable currency, equivalent to a steady and substantial increase in remittances. There would be, inevitably, some cost to the local governments, in that they would either exchange their national currency for PBs, or accept it in taxes (instead of their national currency). But every dollar, pound, yen, rupee or dinar spent in this manner would have many times the stimulatory effect of normal spending, since when you buy one PB, you validate the rest out there in circulation. They could also just just print the money with which to make these transactions, since their own citizens will in most cases accept this as payment.

Governments that do not want to do this, or could not for some reason (a lack of their own currency, for example) could simply introduce a new tax on the wealthy and/or high-income earners, payable in PBs. This would compel these better-off members of society to exchange some of whatever currency they have for PBs. The effect of this transfer would be similarly multiplied as the other PBs in circulation were validated by it. Whether it is stimulatory spending or this tax-driven redistribution, you get much more bang for your buck this way than you would usually.

If it works too well, and the new currency is valued too highly against local currencies, making it difficult for governments to meet their tax obligations without inflating their own currencies, that means we can print and distribute more, until the price of a PB falls (while the value of the basic income increases), or lower these tax obligations.

This plan will not solve every problem, but it would be the biggest economic stimulus, and the greatest step towards ending deprivation, so far in the history of humanity. It is of course optimistic to imagine that our leaders are capable of seeing clearly enough, and acting boldly enough, to set a plan like this in motion. But sometimes a crisis can bring out the best in people, and the economic crisis, which will extend beyond the pandemic, may not give them the option of sticking to conventional responses.

Written by: Austin Mackell