by Guest Contributor | Mar 15, 2022 | Opinion

Universal Basic Income (UBI) takes care of sustenance needs, and SESED (Figure 1), can complement UBI to achieve poverty alleviation. This will be through a small business enterprise, whose success is facilitated by SESED given the peace of mind that UBI provides.

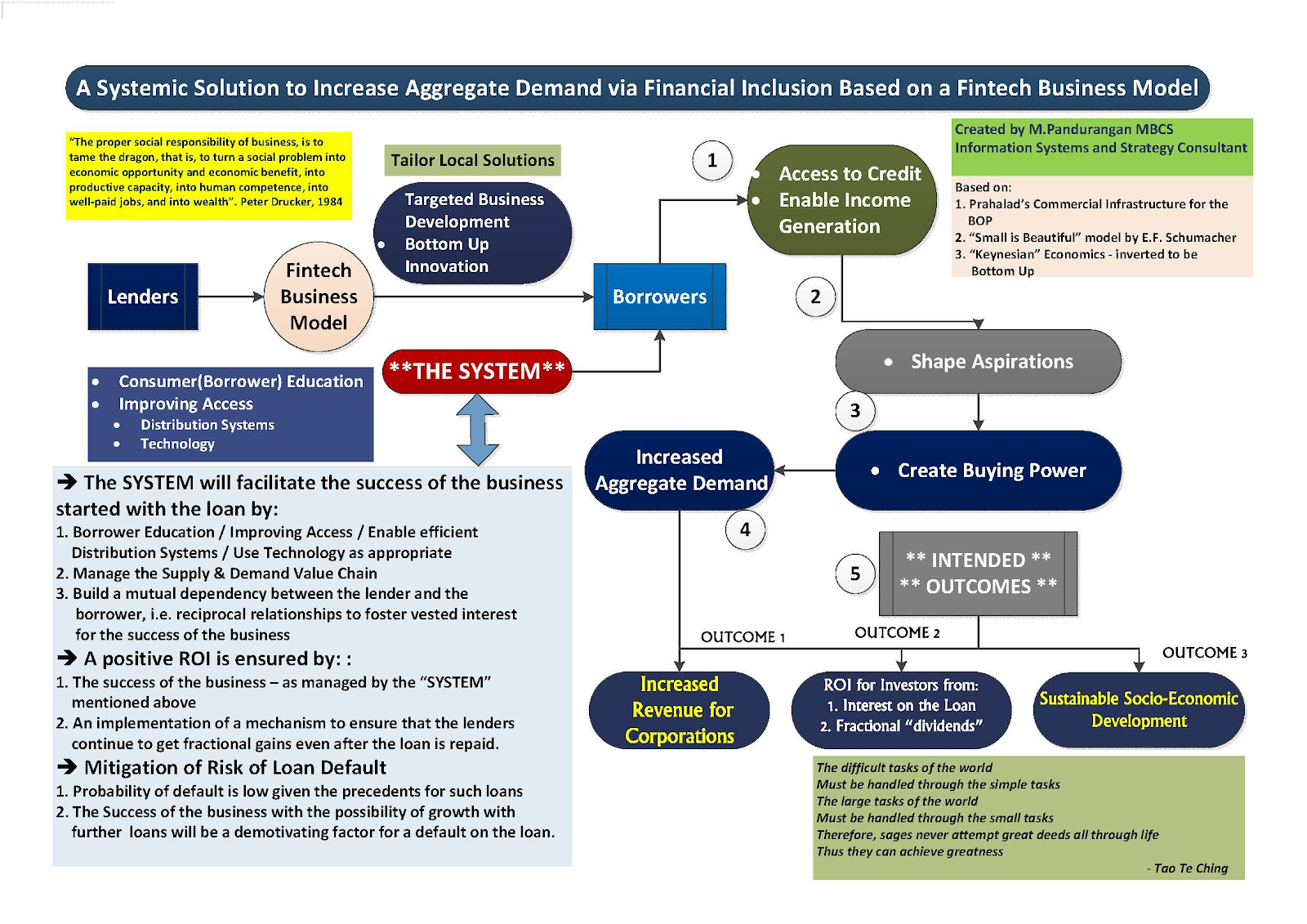

Figure 1 – A Systemic Ecosystem for Socio-Economic Development (SESED)

The SESED is a network of interconnected interdependent small businesses operated by people who are being helped to uplift themselves from poverty. These ventures are initially funded by microloans availed from sponsors, through Fintech companies.

The success of the business is ensured by a strategy of “benefits for all” modus operandi. Thus, the vested interests of all stakeholders are procured upfront.

The access to credit and the success of the enterprise evolves into income generation, from which aspirations, such as education for children, good health by proper nourishment and peace of mind, etc., are shaped.

These aspirations create buying power, now that the funds for these are available.

Though these ventures are small, the overall increased aggregate demand will create a whirlpool in the sluggish economy of the present, and result in a broader, vibrant, and sustainable one.

A key feature for the success of the venture is the “System”. This essentially facilitates the end-to-end process, and whose main responsibilities are:

- Borrower Education – Financial Literacy, Business Acumen, Skills Development, Psychological Interventions, etc.

- Enable access to credit via an efficient income distribution system; e.g., an interface with the Fintech company, manual distribution of funds.

- Manage the Supply and Demand value chain – e.g., suppliers must also be consumers, and vice-versa, of the products of the enterprises as appropriate. This could be along the lines of the Japanese innovation of “Keiretsu”.

- Foster a vested interest from the sponsor in the success of the enterprise for a win-win relationship.

- Tailor local solutions – i.e., targeted business development and bottom-up innovation; e.g., the product could be made available in a cheaper one-time use package, as well the regular one.

- Mitigate the risk of loan default.

- Deal with the idiosyncrasies of the society – e.g., in most 3rd world countries bribes are a norm, and extortions can be present as well.

The late Professor C. K. Prahalad, together with Professor Stuart L. Hart urged corporations to note “The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid”, and espoused “Eradicating Poverty Through Profits”.

It is thus that, not only is the primary outcome of poverty alleviation of UBI with SESED paramount, but they fall through benefits of 1) increased revenue for corporations due to the increased aggregate demand, and 2) the interest on the loans plus “fractional dividends” in the form of profits sharing for the sponsors, that stand out as unique, different and pragmatic in this model.

Thus, UBI with SESED will then be an “Auspicium Melioris Aevi” – an Augury of a Better Age.

M.Pandurangan

linkedin.com/in/mpandurangan

7 Mar 2022

References:

- Standing, Guy – “Basic Income: And How We Can Make It Happen”

- Ruskin, John – “Unto This Last”

- More, Thomas – “Utopia”

- Schumacher, E.F. – “Small is Beautiful”

- Prahalad, C. K. – “The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through Profits”

by Gabriela Cabana | Feb 14, 2022 | News

During January the Fundamental Rights commission of the Constitutional Convention of Chile proposed two different articles to guarantee a basic income. Following an increasing support and visibility of this proposal, the Chilean Basic Income Network collaborated with 11 members of the convention and proposed a basic income as a way of fulfilling the right to a vital minimum (mínimo vital) through a basic income. The articles proposed to be incorporated in the new constitution are:

“Article XXX (to be defined): Of the right to a vital minimum and to the universal basic income.

The State recognizes the human right to a vital minimum.

The State must provide each inhabitant of the Republic with a monetary transfer that is periodic, individual, unconditional and non-seizable.

To ensure this minimum, a sufficient amount of resources must be allocated within the Budget Law for the preservation of social services and benefits.

The law that regulates the organisation and implementation of the basic income will guarantee that, in the case of people in contexts of dependency, the administration of their income is in charge, totally or partially, of their caregivers.

Transitory Article XXX (to be defined): The government will submit a bill for the implementation of the right to a vital minimum and universal basic income within the first two years counted from the entry in force of this constitution”

The second set of articles to guarantee a basic income refers to a right to a guaranteed basic income and it has the following description:

“Permanent article.- Every person permanently residing in Chile will have the right to receive a basic income in money, which guarantees the basic necessities of existence. This income will be monthly, unconditional, individual, unattachable and independent of any other income. The law will determine its amount and provide the way for its transfer to be automatic, without any request or justification. The loss of basic income may not be applied as a sanction.

Transitory article.- The basic income will replace any subsidy with similar purposes and will be implemented in accordance with the progressiveness established by law. The President of the Republic, during the first year of his mandate, must account to the National Congress for the measures that he will adopt for the progression of the effectiveness of this right”.

The next step in this process is the discussion of these initial proposals in the wider assembly. To be approved, an article must gather ⅔ of votes from the 155 convention representatives.

by Enno Schmidt | Feb 11, 2022 | News

The photo of Götz Werner was taken by Enno Schmidt.

The entrepreneur Götz Werner was the best-known and most influential proponent of the universal basic income in Germany since 2005. With him, the UBI became a topic in the media and in society.

His presentation of the idea was also an inspiration and substantial basis for the Swiss popular initiative and vote on UBI and for many other activities of others on the UBI. About two years ago, his state of health no longer permitted any public appearances.

On February 8th, 2022, he passed away in the age of 78.

His strong public appeal and talent to inspire was not only because he had a high social status as a successful and repeatedly awarded entrepreneur, credible with his statements about economy, money and work as someone who had made it in the existing society, but it was his authentic way of putting people first. His presence made others feel joyful, uplifted and assured of a future development despite all the hardships.

His involvement with the UBI was a logical consequence of his entrepreneurial career. For him, basic income was not a contradiction to business, to productivity, but its prerequisite. If you asked him something to which you expected a business answer, he answered with human, idealistic ones. If you asked him something for which you expected a human, ideal answer, he answered in business terms. There was no difference. And what he said lived with the people in the company right down to all the branches at all levels. Not as a parroting of a corporate philosophy, but as an attitude to life and a living space.

The dm pharmacy chain that he founded has today more than 66.000 employees, 43.000 in Germany alone, almost 4.000 branches and an annual turnover of more than 12 billion Euros.

“The company is a platform for biographies,” Götz Werner said. He considered the division between working time and free time to be wrong. Because both are life time. My lifetime is me. I cannot separate myself and my lifetime. Only I can determine my lifetime. No one else can dispose of my lifetime. It is only out of my freedom and determination that I can devote my lifetime to others. But it’s always me. Freedom is not nice talk, it is the very nature of human existence. “The goal of people is freedom-generation“, Götz Werner noted. In the company, people spend their life time, develop skills and unfold their lives. That is what the company is there for. “People are not means, but ends.” They are not a means to the end (purpose) of the company, but the company is a means to the end (purpose) of the people. “A company is a social-artistic cultural event.” In the development of the company, Götz Werner could seem like a sculptor, a social sculpturer, and who sometimes keeps taking a step back to see how it is right and coherent. Action and reflection. He himself changed with his insights and with the changes in the company.

Entrepreneurs create jobs? “Nonsense,” he answered. “No entrepreneur comes into the office in the morning and considers: how can I create a lot of jobs today? Instead, he thinks: how can I optimize processes, how can I do something better for the customers?” But he had created tens of thousands of jobs with the dm drugstore chain, he was further asked. “Where we have opened a new branch, other shops in the area have gone out of business because of it. Previous jobs have been lost where we have offered new ones. New jobs are primarily created today where work is being done to eliminate jobs elsewhere.”

After countless interviews with applicants, a light came on for him: “First people need an income, then they can get involved with our working community and see where they can and want to contribute best.” First an income, then you can engage in the work. Notice the order. That is the order of the free man.

At an event at the University of Karlsruhe, he called out to the thousand listeners: “Your work and the work we all do can never be paid for. But an income makes it possible.” Because my work is my lifetime and my contribution to others. This cannot be paid for because you cannot buy people. Income makes work possible. It does not pay it. “In our society based on the division of labor, we all live from what others do for us. The more productive others can be, the better for me. So it makes sense to create the best conditions for everyone to be productive.” This framework is the UBI. ” Work costs nothing. But everyone needs an income. And everyone works. Even the unemployed. They work too. They also do something. Everyone wants to work, wants to do something that makes sense, for which they experience appreciation.” “Only with the UBI we have a free labor market.” For a free market presupposes the freedom of market participants to be able to say no to a bad offer and yes to a good one. No to underpaid bad or pointless work. Yes to something that makes sense, that I want, even if the pay is not high or it is not paid at all. For Götz Werner, it was evidence from his professional life that made it clear to him that wage dependency stands in the way of real cooperation on an equal footing. Of course, earned income remains beyond the basic income. But the question of existence is not tied to a paid job or the requirements of social welfare. “Today, many people do not have a working place, but only an income place,” Götz Werner remarked. Needless jobs that only give an income and power to the employer to rule about staff. This fits with what David Graeber described in his book Bullshit Jobs.

But how can a UBI be financed, Götz Werner was asked again and again. And again and again he answered: “It’s already financed, isn’t it?” Incredulous amazement on the part of the questioner. “Yes, we live in paradisiacal conditions. We have enough goods and services for all, and we could produce even more. Everything that can be produced can also be financed. Provided one has the good will to do so.” Götz Werner saw: The fact that we are all alive proves that the basic income is already financed. If someone did not have even as much as a basic income, in whatever way, they could not live. This basic income is made unconditional. We look at economics under “a money veil”. We do not live on money. You can’t eat money and you can’t wear money. “We live from what others do for us.” And there is enough of that and could even be more. We no longer live in times of scarcity. That is why the basic income is already financed. Because the goods and commodities and services are there. Money is only a legal means of exchanging goods and services.

And how does the funding take place in practice? Götz Werner’s friend and advisor Benediktus Hardorp had explained VAT to him. Götz Werner understood the advantages. Not elevating taxes where people do something for others, income, but where we all claim the services of others for ourselves, consumption. Much more correct and fairer, much simpler in the calculations. Only value-added tax, all others no more. But he wondered: Where is the social component in VAT? And he came up with it himself: an unconditional basic income amount to all economic participants, that is, to all people, all consumers, paid out at the beginning of the month as a refund of the VAT to be paid in the prices in the extent of the necessities of life. For him, VAT and UBI belonged together. They complement each other and pull in the same direction. Releasing the initiative of the people.

Because Götz Werner’s portrayal of the UBI had grown out of entrepreneurial activity, out of insight and evidentiary experiences, because it did not mean or favor any class of society, but rather the human being in his freedom, of which work is a part, he had an effect on people.

Götz Werner has given his shares in the company to a foundation. When his health began to deteriorate, he decided to bundle his financial support for the debate on UBi into an institution and the science and, together with his wife Beatrice, to endow a professorship at the University of Freiburg. The Götz Werner Chair with Prof. Bernhard Neumärker as chair holder. The dm Werner Foundation also finances the Freiburg Institute for Basic Income Studies, FRIBIS, at the university of Freiburg, Germany.

His son Christoph continues to run the company. He has adopted one of his father’s mottos: “Who want, find ways, who don’t want, finds reasons.”

by Guest Contributor | Dec 30, 2021 | News

The Basic Income March serves as our movement’s annual reminder to pause, take stock and celebrate our progress. This year was full of things to celebrate: from the over 90 pilots taking place across the U.S. to the extended Child Tax Credit – the first national guaranteed basic income legislation for families. While our movement celebrated this momentum across 31 cities – national and local press took notice. Teen Vogue touted the movement as one that resonates with the youth and local outlets took note of local community celebrations of pilot demonstrations.

Basic income advocates organized a variety of different events across the country. While some put on traditional events like marches and rallies, others hosted open skates, enjoyed barbecues at the park, put on concerts, and tabled at art fairs. Organizers did an amazing job on-the-ground of bringing people together for these events safely, taking appropriate COVID precautions.

A new addition to this year’s events was the involvement of organizations leading pilots in their cities. The organizing of the Denver and Chicago events were based on deep partnerships between local volunteer organizers and staff and partners working on Pilots in those cities. This led to strong turnout, great programs, and deeper celebration of local and national progress made for basic income. These were such a success; we anticipate increasing the number of events in 2022 that are led by pilot organizations.

Organizers across the country hosted events that included activities encouraging deep engagement with the community around the idea of basic income. Some provided posters with different financial responsibilities like rent, student loans, childcare, savings, and participants placed stickers next to items they would use a basic income for. Others had people write down a wish for their lives if they received basic income and added it to a collective art installation.

At the core of this celebration and the core of our movement is community engagement. Our design for this year led us to connect with volunteer organizers on a deeper level, the interactive activities during events allowed organizers to connect more deeply with their community and pilot supported events ensured larger turnouts bringing the movement to a wider audience.

It has been a joy to bring together our friends and advocates, both established and new. Along with our partner organizations and organizers, we invite new faces and facets to build on the foundation of our movement. We begin 2022 with gratitude to work in such a dynamic and growing space.

by Lewis Small | Sep 17, 2021 | Featured, News

On 29th April 2021 the prestigious Oxford Union Society hosted a panel of students, activists, politicians and scholars to debate the motion ‘This House Would Introduce a Universal Basic Income’.

The debate began with the majority (68%) voting in favour of introducing a Universal Basic Income (UBI) and the remaining 32% voting against it. After hearing a total of 8 panelists’ arguments for and against the motion, the majority shifted in the closing poll to a marginal victory for the opposition, with 54% voting against introducing a UBI and 46% voting for it.

The full debate can be watched on the Oxford Union’s YouTube channel here, with a programme of the speakers and summary of their key arguments provided below.

00:33 – Opening up the case for the proposition, Classical Archaeological and Ancient History student Ambika Sehgal drew on anecdotal evidence from victims of flaws in the DWP’s (Department for Work and Pensions) systems, experiences from the Covid-19 pandemic, and accounts of early forms of UBI in Ancient Greek societies to make three arguments for the motion:

- To lift people out of poverty and provide a basic standard of living to everybody “without fear or favour”.

- To increase the wealth of the entire population by giving everybody the freedom to upskill, reeducate, take on more prosperous jobs, or start their own business.

- To prevent the inevitable economic catastrophe that we are approaching as a result of the automation of skilled industries.

10:52 – Rebutting with the opening case for the opposition, Eliza Dean, first year Classics and French student and Member of the Union’s Secretaries Committee, denounced UBI as the solution to our current economic and political struggles, arguing instead for better funding of existing state welfare systems and a return to greater recognition of the value of labour in society.

20:58 – Professor Guy Standing, Professorial Research Associate at SOAS University of London and founding member of BIEN, outlined the fundamental ethical – as opposed to instrumental – rationale for introducing a UBI, arguing that we have an ethical justification to introduce UBI to resolve the unequal distribution of wealth created by rentier capitalism.

Rounding off his argument for the proposition, Professor Standing drew on his extensive experience working on over 50 pilots to outline some of the key findings of research on UBI:

- It improves individual mental and physical health.

- It reduces people’s stress.

- It leads to better school attendance.

- It increases work and its productivity, leading people to be more innovative and altruistic in their work because people feel more able to act in such a way.

- It helps to reduce debt.

- It leads to a greater sense of social solidarity.

36:34 Marco Annunziata, former Chief Economist and Head of Business Innovation Strategy at General Electric, invoked suggestions for the necessary rise in taxes, the case to offer the same amount to the rich and poor, and the disincentives to work as evidence that a UBI is both unaffordable, unjust and riddled with unintended consequences.

48:53 Drawing on simulations run by the RSA (Royal Society for Arts, Manufactures and Commerce) Anthony Painter, Chief Research & Impact Officer, made the economic case for UBI, citing its ability to make up for inadequacies in existing social support systems by offering a hardwired economic platform for all in society.

59:50 Regarding UBI a ‘recurring revenant’ throughout his career, Professor Hilmar Schneider, Director of the Institute of Labour Economics in Bonn, cited the experience of the German pension system and his own research conducting funding and behavioral responses simulation models to argue against the motion. Pointing to the fact that most UBI pilots rely on external funding sources, Professor Schneider argued that the strongest argument against a UBI lies in its unaffordability, as it would ultimately result in more people losing money than gaining money.

01:10:34 William Greve, first year Philosophy, Politics and Economics student and Sponsorship Officer at the Oxford Union,consolidated the arguments made by the panelists to round off the underlying economic and liberal arguments for a UBI:

- That is the most effective way to counter the wealth inequality and unjust returns to capital observed in the modern economy that leave labour so unjustly rewarded.

- That it is reasonable to demand that all individuals in a society be entitled to a share of the total wealth of society a basic level of economic security.

- That it would fundamentally change our relationship with employment for the better.

Drawing on Professor Schneider’s earlier remarks on the case against higher income taxes (owing to the fact that the majority of wealth that exists in the modern economy is not received as an income in the traditional sense), William also argued that a wealth tax, not an income tax, is the most just and feasible way to fund UBI.

01:21:30 Rt Hon Jon Cruddas, Labour MP for Dagenham and Rainham and Former Coordinator for the Labour Party, rounded off the case for the opposition by arguing that those advocating for UBI should remain cautious when their political opponents also support the scheme for radically different outcomes. Noting the many cross-spectrum and cross-ideological arguments for and against the motion, he also pointed to the more ‘mundane and practical’ issues with introducing UBI, such as financial feasibility, its efficacy compared to its alternatives, and what accompanying policies are required to ensure desired outcomes.

Concluding the case against UBI, Rt Hon Cruddas hammered home his argument for the dignity of labour and questioned the role that UBI would play in creating decent work. All but entirely dismissing concerns around automation and the future availability of work, he argued that we should instead be organizing for collective rights, strong unions, income guarantees and above all, dignified labour. He argued that there is a strong case against UBI if you consider that the nature of work thesis is flawed, and that the debate around the future of work is an inherently political one. UBI, he suggested, could transform citizens into ‘passengers of capitalism’, robbing them of meaning and dignity, and leaving them more isolated, vulnerable, angry and humiliated, and society itself less fraternal and solidaristic.