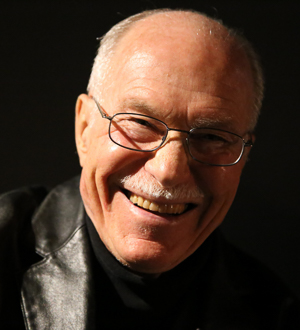

David Graeber has died at the age of 59

BIEN joins with many people around the world in mourning the sudden death of David Graeber, Professor of Anthropology at the London School of Economics, at the age of 59.

BIEN joins with many people around the world in mourning the sudden death of David Graeber, Professor of Anthropology at the London School of Economics, at the age of 59.

This short video introduces the new book, The Prehistory of Private Property, by Grant McCall and me. The book examines the origin and development of the private property rights system and the experiences of peoples who have lived in other systems to debunk three false claims commonly accepted by contemporary political theorists. These false claims are: (1) Inequality is natural and inevitable, or egalitarianism is unsustainable without a significant loss in freedom. (2) Capitalism is more consistent with negative freedom than any other conceivable economic system. (3) Private property is somehow “natural,” meaning that when free from interference people tend to appropriate and transfer property in ways that lead to a capitalist system with strong, individualistic, and unequal private property rights.

The book presents a great deal of anthropological and historical evidence that show that all three of these claims are false: (1) Many societies known to anthropology have maintained egalitarianism and freedom. (2) The least free people under capitalism are significantly less free than people in societies with common access to resources. (3) The first people to “appropriate” property tend to share resources; the elite private ownership system was forced on the world by the colonial and enclosure movements beginning only about 500 years or so ago and not fully complete yet.

The book is not primarily about Universal Basic Income (UBI), but it attacks many arguments used against UBI and other forms of redistribution. It also makes a brief case for UBI in the very last chapter, as the video explains.

As a bonus, early in the video, if you look closely, you can see Alexander de Roo eating breakfast in the background.

Thanks to Ali Mutlu Köylüoğlu for inviting me to give this talk and for recording and posting it.

-Karl Widerquist, Morehead City, North Carolina, June 17, 2020

Executive Committee posts and postholders

Sarath Davala is an Indian sociologist based in Hyderabad, India. He co-founded India Network for Basic Income and Mission Possible 2030 – both organisations working on basic income related issues. From 1993 to 2000, he was an Associate Professor at the Indian Institute of Management Bangalore. Between 2010 and 2014, he was the Research Director of the Madhya Pradesh Basic Income Pilot Project. He is the co-author of the book: “Basic Income: A Transformative Policy for India”, which summarised the findings of the MP BI pilot study. He is currently co-leading another basic income pilot with waste collectors in the city of Hyderabad, India, a project initiated by University of Bath, and supported by European Research Council. Sarath is also collaborating with different agencies to innovate solutions to reach cash the last mile in the rural parts of India.

Hilde Latour has a background in biomedical sciences and cultural anthropology and years of experience in program and knowledge management. She is a life member of BIEN, board member of Basisinkomen Nederland (Dutch BIEN) and co-founder of Mission Possible 2030 – Basic Income the key to SDG. As a guest lecturer at the blockchain minor – International Financial Management and Control at The Hague University of Applied Sciences, she explores the boundaries of paradigm shifts, such as Building Commons on the blockchain, a new narrative for Basic Income.

Lindsay is a Professor of Public Law at the University of Sussex. His academic interests are wide-ranging academic, spanning administrative law and public administration in the UK and elsewhere. Lindsay’s interest in basic income has to date been centred on the administrative analysis of basic income policies, and he has published widely on this topic. More recently, Lindsay’s interest has extended to understanding the dynamics of political and governmental support for basic income policies, in which the administrative factor is just one of several components.

Lindsay lives in Seaford, on the South Coast of England, where he serves as Liberal Democrat Town Councillor for the Seaford South ward.

In his spare time, Lindsay trains for and runs marathons.

Fabienne Hansen is a PhD student in social anthropology at the University of Freiburg, Germany. She is also associated with Universidade Federal Fluminense in Niterói, Brazil, where she looks at the integration of UBI within municipal social policies in Brazil. Generally, Fabienne is interested in the effects basic income could have on everyday livelihoods as well as the shaping of policyscapes that stand behind policy decisions. She was elected BIEN Secretary in 2024.

After serving three years as BIEN Secretary, Diana will focus her work within BIEN on expanding BIEN’s partnerships with United Nations entities, presenting basic income as a complement to international development and peacebuilding efforts. This builds on BIEN’s collaboration with UNDP, the Office of the UN Secretary-General, the UN Peacebuilding Support Office and UNIDO, which Diana has led since 2021.

Diana is a PhD candidate at the University of Vienna researching basic income’s potential for social cohesion. In the past, she has worked for the United Nations and the French Development Agency in Damascus, New York and Vienna. Diana was elected BIEN UN Liaison in August 2024.

James has been contributing to BIEN’s online presence since 2018, becoming the Social Media Manager for the organisation in 2021. He studied International Relations at Queen Mary, University of London, and currently works in the tech sector.

Julio Linares is an economic anthropologist from Guatemala. He holds an MSc in Anthropology and Development from the London School of Economics and Political Science and a MA in Applied Economics and Social Development from National ChengChi University (國立政治大學) in Taipei, Taiwan. His research focus dwells on the relationship between money, direct democracy and unconditional basic income. Julio is currently based in Berlin, Germany, where he explores these topics in practice with the Circles UBI project. Julio is currently serving his second term as Public Outreach for BIEN. He speaks Chinese, English, Spanish, German and a bit of Hungarian.

Jurgen De Wispelaere is a political theorist turned public policy scholar, specialising in the political economy of basic income. He has published extensively on the politics of basic income, including most recently on basic income and crisis politics, basic income as national-regional-local policy, and the political origin story of basic income in Maricá (Brazil) and its diffusion across Rio de Janeiro state. He is the co-editor of four volumes as well as the Founding Editor of the interdisciplinary journal Basic Income Studies. Jurgen was a member of the BIEN EC in 2002-2004 and co-organised the BIEN Congresses in Montreal (2014) and Tampere (2018). He is currently leading the UBIdata Project for BIEN.

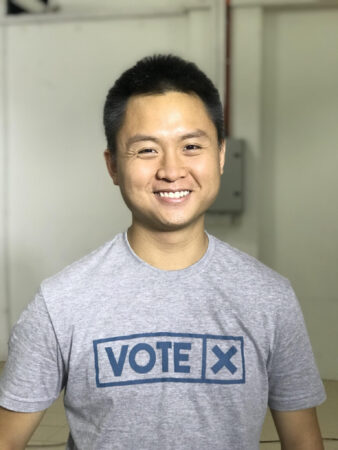

Prior to his career in architecture and project management, Seng Kiat coordinated volunteers as polling and counting agents nationwide to observe the momentous 2018 Malaysian General Election. Since moving from Kuala Lumpur to London, Seng Kiat volunteered for BIEN before serving as Volunteer Coordinator. Seng Kiat has advocated for Basic Income from 2019 and resonates with BIEN’s role in fostering discussions over Basic Income. He is also fluent in Malay and Mandarin. Seng Kiat was elected BIEN’s Volunteer Coordinator in August 2024.

Dr. Neil Howard is Reader in International Development at the University of Bath, where he leads UBI Bath, the UK’s first centre of basic income scholarship. He is an anthropologist of development turned social protection scholar. His research investigates the governance of exploitative labour practices, as targeted for eradication by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). He also explores innovative forms of labour and social protection, focusing on Unconditional Basic Income (UBI) combined with participatory community organizing. Neil co-led two international policy experiments trialling this combination in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and Hyderabad, India. He also sits on the Executive Committee of the Basic Income Earth Network.

Olaf Michael Ostertagis based in Berlin, Germany, and has been a grassroots activist for Basic Income since 2004. He co-founded the “BAG GE” (Basic Income Working Group) within the political party DIE LINKE (“The left”), together with Katja Kipping, Ronald Blaschke, Stefan Wolf and others. This action committee was successful in convincing a majority of this party’s membership to adopt Basic Income as a political demand until recently.

His first professional education was actor’s training, at Valentin Plátáreanu’s studio. Olaf wrote over two dozen satirical plays for ensemble casts and stand-up comedy shows, the latest of which he is currently performing in Berlin. Olaf worked briefly as a journalist and as office manager for members of parliament, on state and national levels.

In 2017, he began training as a tax accountant and has worked at the same consultancy firm consecutively since 2018. He currently chairs two charities in Berlin: A local history association and an artist’s social club.

As Affiliates Coordinator, he aims for collecting the knowledge, experience and objectives from all over the world, and hopes to be able to foster exchange and inspiring debates between BI activists from different backgrounds. He encourages to reach out to him to induce conversations: olaf [(at)] basicincome.org

Peter Knight joined BIEN in 2017. He is a PhD (Stanford University) economist and strategic analyst with broad international experience in digital transformation, e-development, e-government, distance education, electronic media, telecommunications reform, international banking, foundation work, and teaching. Peter is devoted to leveraging information and communication technologies to accelerate social, economic and political development. He currently focuses on promoting thought, communication, and action across three areas: sufficiency, sustainability, and innovation; he is Coordinator of the Sufficiency4Sustainability Network.

Tyler Prochazka is the opinion editor for BIEN. He is the chairman of UBI Taiwan and a PhD student at National Chengchi University.

Bank account trustees (not members of the Executive Committee): Jacob Eliot, Anne Miller, Simon Duffy, Reinhard Huss

Chair of the International Advisory Board: Philippe Van Parijs

The task of the EC

BIEN’s purpose is: To educate the general public about Basic Income, that is, a periodic cash payment delivered to all on an individual basis, without means test or work requirement; to serve as a link between the individuals and groups committed to, or interested in, Basic Income; to stimulate and disseminate research about Basic Income; and to foster informed public discussion on Basic Income throughout the world.

The task of the EC is to ensure that BIEN fulfils its constitutional purpose and to set policy to that end.

General duties of EC members

Individual duties

Chair

The role of the Chair is to collectively develop a vision, mission and long-term strategy for BIEN. In all aspects the Chair should work closely and in consultation with the Deputy Chair.

She / he should seek new partnerships globally and develop meaningful collaborations with people and organizations that will further the strategic objectives of BIEN in terms of strengthening research about Basic Income, its dissemination worldwide in as many languages as possible so that basic income discussion becomes rigorous and robust. In addition to these strategic aspects of the role, Chair in consultation with the Deputy Chair and the EC members should fulfil the following tasks:

Deputy Chair

Secretary

Treasurer

Hubs Supervisor

The Hubs Project involves building regional BIEN hubs in Africa, Asia and Latin America and professionalising BIEN’s day-to-day activities. The project aims to strengthen the basic income ecosystem and BIEN’s role in it.

News Service Editor

Social Media Manager

Affiliate and Public Outreach

Volunteer Coordinator

Research Coordinator

Congress Organiser (appointed by the EC and the Local Organizing Committee)

Website Manager

Bank account trustees

This is a draft version of my forward to the book, Implementing a Basic Income in Australia: Pathways Forward edited by Elise Klein, Jennifer Mays, and Tim Dunlop New York: Palgrave-Macmillan 2019

Back in 1999, when I first started following international developments on Basic Income (BI), not much was going on in Australia. Allan McDonald had been writing about BI in the newsletter for a group called Organisation Advocating Support Income Studies in Australia (OASIS-Australia), but when he stepped down in 2002, no one was available to take over.

But over the last several years, interest in BI in Australia has picked up greatly. Australians inside and outside of academia are producing a lot of research and literature on it, and that work is beginning to have a major impact on politics. Australia’s two major parties might not yet be ready to endorse BI, but they can no longer ignore it. And in fact, the Australian Greens, a party that often holds the balance-of-power in Australia’s federal Upper House, have officially adopted BI as party policy.

Australia has become not simply one of the countries where BI is regularly discussed, but very possibly a major world centre for UBI activity. One sign is that the Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN), the only worldwide BI network, has selected Australia for the location of its 2020 conference.

Another sign became obvious to me in 2017 when Elise Klein invited me to come to Australia to speak at a BI conference. Members of Basic Income Guarantee Australia (BIGA) took the opportunity to set me up for as many talks or meetings as I could do in the time I had. That turned out to be a whirlwind of seven appearances in four days in three cities—Canberra, Sydney, and Melbourne. I spoke with members of parliament, with members of the media, with academics, and with university students. I slept on a train and on a plane, and I managed to stay awake for all or most of the two-day, BI research conference in Melbourne, where I learned a lot and had the chance to meet many of the authors of this book. I was impressed by the breadth and depth of BI work going on in Australia.

A third sign that Australia has become a major world centre for BI research can be found in the publication of the book, Implementing a Basic Income in Australia: Pathways Forward edited by Elise Klein, Jennifer Mays, and Tim Dunlop (Palgrave Macmillan 2019). It includes a dozen authors from fields as diverse as Anthropology, Development, Economics, Geography, Journalism, Political Economy, Political Science, Public Health, Social Work, and Sociology. It addresses major empirical and philosophical issues of implementing BI in Australia. Although all or most of the chapters are written in a way that will be interesting to an international audience, parts of the book’s focus is on issues that will be especially interesting in the Australian context, such as the specific problems and opportunities for BI in very remote areas as well as its value as a tool to counter the effects of Australian settler colonialism.

The book pays special attention to the political barriers in the way of implementation of BI in Australia and to the opportunities and prospects for political strategies to move BI forward. These include proposals to start with group-focused transfers, such as BI for young people; proposals for how community groups, professionals, and activists can effectively advocate for BI; and proposals for fitting BI into the existing welfare system.

Although these lessons come from the Australian context, the value of this book for the BI movement all over the world needs to be appreciated. It’s a book about implementation—an issue that needs much more analysis by the global BI researchers and activists. Social, economic, and political strategies for BI need to be explored in different ways in every conceivable context. Comparative analysis of different strategies in different contexts is how we’ll truly learn what works and what doesn’t, and this book provides a valuable contribution to that effort.

The book is an excellent read and a valuable resource for researchers, students and anyone interested in BI.

-Karl Widerquist, Doha, Qatar, December 8, 2018

Table of contents (14 chapters)

Pages 1-20

Klein, Elise (et al.)

Pages 23-43

Marston, Greg

Pages 45-68

Mays, Jennifer

Pages 69-85

Cox, Eva

Pages 87-109

Altman, Jon (et al.)

Pages 111-126

Bowman, Dina (et al.)

Pages 129-145

Hollo, Tim

Pages 147-161

Quiggin, John

Pages 163-178

Spies-Butcher, Ben (et al.)

Pages 179-198

Kaighin, Jenny

Pages 199-213

Scott, Andrew

Pages 215-235

Ablett, Phillip (et al.)

Pages 237-257

Mulvale, James P. (et al.)

Pages 259-262

Klein, Elise (et al.)

My latest book project (coauthored by the anthropologist, Grant S. McCall) is called The Prehistory of Private Property. It book tells two parallel histories. It tells the story of how modern property theory became dependent on three misconceptions about the origin of the property rights system and the difference between societies with common and privatized resources, and how those misconceptions continue to have a negative effect on contemporary political thought and beliefs about our shared responsibility. The second story traces the origin and development of the private property system through history and prehistory to debunk those misconceptions.

The three claims at the center of this book are: 1. The normative principles of appropriation and voluntary transfer applied in the world we live in can only support a capitalist system with strong private property rights. 2. Capitalism is more consistent with negative freedom than any other conceivable economic system. 3. Inequality is natural and inevitable, or egalitarianism is unsustainable without a significant loss in freedom.

The book devotes a great deal of space to show how these misconceptions are embedded in many influential theories in political philosophy, because political philosophers are often unclear about the extent to which their theories rely on empirical claims. The clarity problem is nearly as important as the dubious nature of the claims. Obscurity and ambiguity help shield these claims from scrutiny.

Underlying this specific theoretical agenda is the more general goal of raising the level of discussion of empirical issues in political philosophy. Ambiguous allusions to empirical claims should be unacceptable in any academic literature. Philosophers have the responsibility to be clear about what empirical claims they rely on and about the level of support they can offer for those claims. Their critics should not let them get away with the sloppy use of ambiguous allusions to empirical claims.

Once the need for each claim is clearly established, the book subjects each claim to rigorous empirical investigation using the best evidence available from anthropology, and then discusses the implications of those findings for contemporary theory. Some of the book’s central findings follow.

The book is not directly about Basic Income, but it will connect to the idea in the final chapter. We will argue that the mass of humanity lead lives of manufactured desperation. People are not naturally in a struggle to “find work” to ensure they have food, shelter, and clothing. They are artificially put in this situation by a stratified property rights system that is not necessary for human social organization and that most societies (from the earliest hunter-gatherers to more recent peasant farming systems) did not find it necessary to manufacture such desperation. Basic Income is one way to compensate people for the imposition of a stratified property system and to relieve them of desperation that has come with it.

We have full drafts of 8 of the books ten chapters, and we are positing them online at this link as they reach presentable form. We hope to have a full draft we can send to our publisher (Edinburgh University Press) within a few weeks or months.