by Kate McFarland | Apr 8, 2017 | Research

Matthew Dimick, Associate Professor of Law at University at Buffalo, has written a new article for the Indiana Law Review in which he compares the promises of basic income to those of working-time regulation, presenting a case to prefer the latter.

According to Dimick, the potential benefits of working-time regulation outweigh those of basic income, in large part because they would be shared more equitably throughout the population. For example, on Dimick’s assessment, a basic income would not allow the majority of people to increase their leisure time (a benefit he sees as largely confined those who “earn subsistence-level incomes or lower” and thus “would have either the option not to work or the bargaining power to secure a more favorable work-leisure trade-off with employers”); working-time regulation, in contrast, would increase leisure time for middle- and even upper-class workers as well. Additionally, Dimick argues that working-time regulation could allow not only leisure but also jobs to be more widely available and equitably distributed — whereas a basic income would deepen the divide between the working and non-working populations.

And working-time regulation might have other positive effects. For instance, due to the across-the-board increase in leisure time, Dimick contends that the policy would likely result in decreased consumption, while a basic income might spur additional consumption — leading to a preference for the former from an ecological viewpoint.

Further, because working-time regulation is a less radical departure from current policies — and, in particular, does not aim to sever benefits from work — it is much better positioned to gain popular and political support.

Dimick notes that basic income might do more than working-time regulation alone to “transform the workplace” (e.g. by giving more bargaining power to employees themselves) but that, with respect to this goal, working-time regulation should be conceived as part of a larger set of legislative reforms.

Matthew Dimick’s current areas of research include labor and employment law, tax and welfare policies, and income inequality. He holds a PhD in Sociology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he studied organized labor under Erik Olin Wright and Ivan Ermakoff, and a JD from Cornell Law School.

Matthew Dimick, 2017, “Better Than Basic Income? Liberty, Equality, and the Regulation of Working Time,” Indiana Law Review.

Post reviewed by Genevieve Shanahan

Photo CC BY-ND 2.0 Laurence Edmondson

by Genevieve Shanahan | Apr 6, 2017 | News

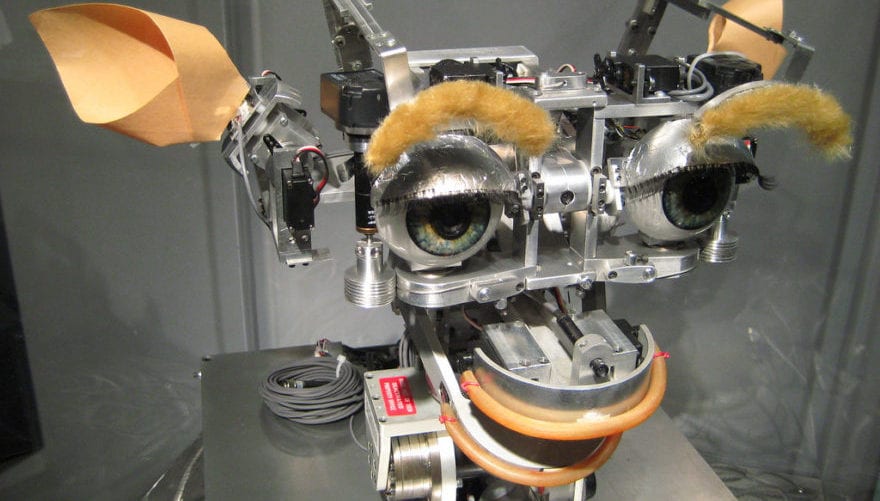

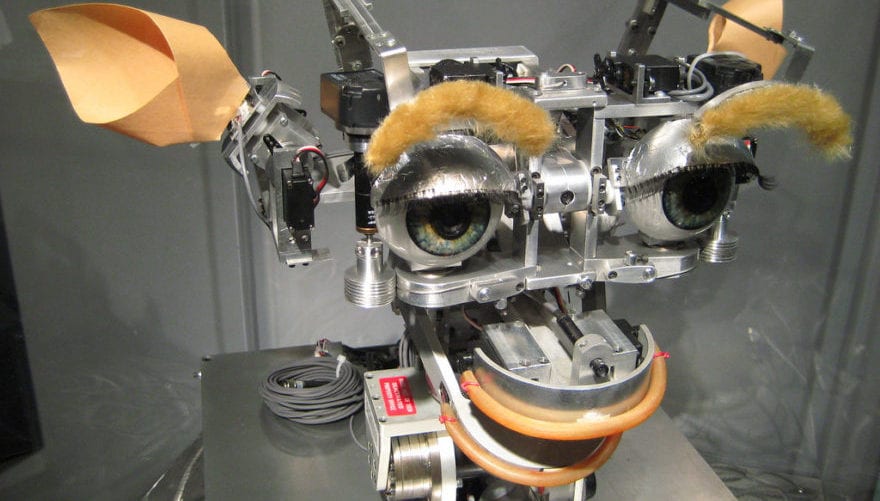

The MIT Tech Conference, an annual event hosted by the MIT Sloan Tech Club at the MIT Media Lab, took place on Saturday, February 18th this year. TechTarget reports an impassioned exchange regarding basic income that occurred at the conclusion of a panel on the current state of robot technologies. Universal basic income was “largely seen as the best answer to taking care of a displaced workforce,” though the challenges of such proposals were also addressed.

This discussion of basic income arose from points made regarding the rise of automation and the associated predicted loss of jobs:

“To be sure, embracing and adopting technology has always been a competitive advantage. Horses, for example, used to be a major force by which work got done; they labored alongside humans to plow fields and deliver goods, but they were sidelined by advances from the second industrial revolution.

“Liam Paull, research scientist in the distributed robotics lab at MIT’s CSAIL and the panel moderator, asked panelists if robotics will present a scenario where humans are the horses? The comparison was crude, but the point was clear: When robots perform factory jobs or drive trucks better than humans, those careers disappear forever.”

Points raised over the course of this discussion, reported by TechTarget, include the following: that new, unforeseen jobs may emerge when existing jobs become obsolete; that automation risks exacerbating inequality both within the US and around the world; and that more evidence is necessary before solid policy recommendations can be made.

Nicole Laskowski, “Roboticists: Universal basic income demands attention,” TechTarget, March 2017

Reviewed by Russell Ingram

Photo: MIT Robotics, CC BY-NC 2.0 Adrian Black

by Kate McFarland | Apr 4, 2017 | News

Paul Basken has written an article about scholarly research on basic income for The Chronicle of Higher Education, a US-based news service aimed toward individuals engaged with higher education.

Despite concerns about job loss due to automation, and despite an increase in the popularity of basic income as a potential countermeasure, it is rare that university researchers in the United States seek (let alone obtain) funding for research projects on basic income. As Basken’s article points out, the National Science Foundation (NSF), the main federal agency sponsoring academic research, has not received a “surge in proposals for research on basic income” — nor has it made any strides to encourage such topics.

However, as Basken also notes, many scholars are themselves not sure what research could reveal about the implementation and effects of basic income, given the inherent limitations of experiments and simulations and the complexities of implementing the policy in practice.

Basken’s article features commentary from three scholars who have researched and written upon basic income: Michael C. Munger (Political Science, Duke University), Michael A. Lewis (Social Work, Hunter College), and Matt Zwolinski (Philosophy, University of San Diego).

Read the full article:

Paul Basken, “Universal Basic Income: An Idea Whose Scholarly Time Has Come?” The Chronicle of Higher Education, March 9, 2017.

Reviewed by Robert Gordon

Photo CC BY 2.0 Stewart Butterfield

by Guest Contributor | Apr 4, 2017 | News

According to a recent survey, 61% of Flemings agree that “everyone should have the right to a guaranteed basic income”. About a quarter say that, if guaranteed this right, they would start their own business, and women in particular would be more entrepreneurial.

The questions about a basic income guarantee formed part of a larger survey on the economy, conducted by Trendhuis (“Trend House”), a research group that has been following trends in public opinion in Belgium since 2005. For its survey on the economy, which was released in January 2017, it polled 1,028 members of the Flemish population (Dutch-speaking Belgians) over the age of 18.

In the web-based survey, Trendhuis asked respondents whether they support a basic income, defined as a fixed (monthly) income provided by the government to all citizens, without means test or work requirement. As seen in the table below, a majority in each demographic group analyzed — young and old, male and female, “short-” and “long-” educated — supported the idea. The greatest support came from the 51-65 age group, in which 67% of respondents favored basic income.

These results are roughly consistent with those found in Dalia Research’s EU-wide study of attitudes about basic income, conducted in April 2016.

More Entrepreneurship

Survey subjects were further asked about entrepreneurial activity. Overall, 20% of the respondents indicated that they would set up their own company in the future even without a basic income, while 25% would do so if they were provided with a basic income.

The difference was more pronounced for women: 14% said that they would start their own business in the future without a basic income; this proportion jumped to 23% with a basic income.

Changing Behavior

One of the big questions of the basic income debate is whether people will still be motivated to work with a guaranteed basic income. In the Trendhuis study, 6% of the Flemings surveyed indicated that they would completely give up their jobs. More than one in three said that they would consider working less (for example, part-time or four-fifths)–with women (40%) more inclined to do so than men (31%).

Almost half of those surveyed said that they would find work better suited to their abilities (47%) and commit more time to volunteering (45%). Additionally, four in ten respondents said that they would study. More than half of the women expressed an intention to commit to voluntary work (54%), versus 39% of men.

Figures

“I think that everyone should have a right to a guaranteed basic income”

(Percentages = ‘agree’ + ‘strongly agree’)

| Overall |

61,06% |

| Men |

59,46% |

| Women |

62,70% |

| 20-35 y.o. |

58,00% |

| 36-50 y.o. |

56,07% |

| 51-65 y.o. |

67,22% |

| Short Educated |

63,29% |

| Long Educated |

60,28% |

“If I had a right to a guaranteed basic income, I would…”

(Percentages = ‘agree’ + ‘strongly agree’)

|

Overall |

Men |

Women |

20-35 |

36-50 |

51-65 |

Short Ed. |

Long Ed. |

| Start own business |

24,90% |

26,39% |

23,34% |

37,05% |

28,28% |

11,98% |

19,12% |

26,91% |

| Volunteer more. |

46,09% |

38,96% |

53,95% |

49,87% |

46,17% |

43,80% |

38,80% |

48,62% |

| Work less. |

35,23% |

31,11% |

39,79% |

37,00% |

37,17% |

35,37% |

31,87% |

36,39% |

| Stop to work. |

5,85% |

5,07% |

6,71% |

2,73% |

3,79% |

10,83% |

7,76% |

5,18% |

| Find work that better fits my talents. |

46,65% |

46,47% |

46,95% |

51,30% |

43,24% |

45,83% |

51,17% |

45,07% |

| Return to school. |

42,50% |

42,49% |

42,62% |

52,81% |

40,71% |

33,99% |

38,42% |

43,92% |

| Negotiate for better work conditions. |

24,06% |

26,86% |

21,08% |

28,10% |

24,65% |

20,15% |

26,07% |

23,37% |

|

“I see myself starting up a company in the future”

(Percentages = ‘agree’ + ‘strongly agree’) |

“If I had a guaranteed basic income right then I would set up a private enterprise” (Percentages = ‘agree’ + ‘strongly agree’) |

Difference in percentage points |

| Overall |

19,48% |

24,90% |

+ 5,42 |

| Men |

24,27% |

26,39% |

+ 2,12 |

| Women |

14,41% |

23,34% |

+ 8,93 |

| 20-35 y.o. |

33,22% |

37,05% |

+ 3,83 |

| 36-50 y.o. |

21,53% |

28,28% |

+ 6,75 |

| 51-65 y.o. |

7,26% |

11,98% |

+ 4,72 |

| Short Educated |

13,46% |

19,12% |

+ 5,66 |

| Long Educated |

21,58% |

26,91% |

+ 5,33 |

Edited by Kate McFarland; reviewed by Genevieve Shanahan.

Photo CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Daniel Mennerich

by Michael Lewis | Apr 2, 2017 | Opinion

Written by: Michael A Lewis

As someone interested in basic income (BI), I read a fair amount about the topic. I read pieces by supporters and opponents, as well as those who might be considered more neutral. I’m often struck by the degree of uncertainty concerning implementation of BI.

A popular argument for BI these days is based on concerns about the possibility of mass technological unemployment. Some in the “tech industry” contend that BI will become necessary as automation replaces more and more human laborers in the years to come. This has led to a debate among economists and others regarding whether automation will result in a net loss of jobs (for humans) big enough to warrant the need for something like BI. Both sides of this debate bring evidence to make their cases. But in the end, we simply don’t know for certain if and when automation will lead to a net loss of jobs for us human beings.

Assuming BI might be implemented in a society which would still require a fair amount of human labor power, we’d like to know what impact BI would have on people’s inclination to sell their labor or, more commonly, “work.” A BI could affect labor supply in at least two ways.

One is that people who received an income they didn’t have to work for may be inclined to work less. The second possible effect has to do with how BI would be financed. If it were financed by an increase in income taxes, this could also reduce labor supply. The reason is that a large proportion of many people’s incomes are earnings, meaning that an income tax is largely a wage tax. A higher wage tax has two possible effects on labor supply.

On the one hand, such an increase could cause people to work less because with the higher tax (and all else equal) their take home pay is smaller than it was before, creating an incentive to work less. On the other hand, a smaller take home pay means one would have to work more than before to maintain their standard of living. This would create an incentive for people to work more not less. If BI were implemented, we have no way of knowing which of these effects would dominate the other.

Leaving the labor market (but still related to it), another area of uncertainty has to do with how people would spend their time, assuming they did reduce their labor supply. Opponents of BI worry that people would use their time “unproductively”, while proponents tend to argue that individuals would engage in more care work or pursue “self-actualization” through pursuing education, writing poetry, starting a business, and the like. But if we’re being honest, regardless of which side of the debate we’re on, we must admit that we don’t have much of an idea what the relative proportion of unproductive to productive activities would be, assuming we could even agree on how to categorize activities as unproductive or productive.

A third area of uncertainty is related to personal relations and household composition. BI could have an effect on who lives with whom, who marries whom, who has kids or not (as well as how many to have), etc. As a society, we obviously differ when it comes to our values about such matters, meaning we might differ on the desirability of BI. But we don’t really know for sure how implementation of BI would affect “family life.”

Now I’m not saying we’re completely in the dark when it comes to questions of BI’s effect on labor supply, use of non-wage time, etc. Economists, sociologists, and others can draw on theory to help us think through these matters. And, by this point, there’ve been several experiments/studies (as well as more recent “startup” studies) which offer a lens on what might happen if BI were implemented. But we should be careful not to overestimate how much help we can receive from such experts, as well as the studies that have been (and are being) conducted.

Considering the many BI experiments (as well as proposed ones) around the world, we need to be cautious about what lessons might be learned. The philosopher Nancy Cartwright, well known for her work in the philosophy of science, has a phrase that’s quite relevant to this discussion: “it works somewhere.” Cartwright frequently utters this phrase within the context of discussing randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the so called gold standard of empirical research in the social sciences. Her point is that even if a well-designed RCT shows that a policy works in one context, that doesn’t necessarily mean it’ll work in another one. This is relevant to BI studies because they’re being conducted, or proposed, in a variety of different contexts. So if we find out that something works in India or Finland, that doesn’t mean it’ll work in Japan or the U.S. In the article cited above, Cartwright goes into great detail about why generalizing experimental findings from one context to another can be so difficult. For those interested in what we might learn from BI experiments, I think her work is quite instructive.

When engineers design systems, such as buildings, bridges, etc., they also must face uncertainties. To be double sure of the approaches that they take, many engineers tend to avail the services of engineering consultancy firms, so that they can rest easy knowing they are backed up by the same opinion. However, they don’t know for sure what loads the systems will end up having to bear, they don’t know if there will be earthquakes, they don’t know how forceful the winds will be, etc. One of the things engineers do to deal with such uncertainties is to include safety factors in their designs.

For example, suppose an engineer is designing a structure and wind, seismic, and other data indicate that it’ll have to bear a load of 1000 kg. Suppose also that the engineer wants a safety factor of five. Then the load which the structure should be able to bear isn’t 1000 kg but 5×1000 = 5000 kg. So a safety factor is a multiple used to increase the strength or robustness of a system beyond that which is thought to be required to account for uncertainty in what’s thought to be required.

Those of us designing policies don’t have the luxury of being able to use simple equations, which include safety factors, the way engineers do. But perhaps we should adopt a similar safety factor mentality. Implementation of BI would be a complicated undertaking, involving a great deal of uncertainty. Perhaps BI supporters should consider how to increase its robustness in response to labor supply reductions, as well as other unanticipated effects. I admit I’m not exactly sure how to do this. But I believe it’s something worth thinking about.

Michael Lewis