by Guest Contributor | Apr 9, 2022 | Opinion

Which country in the world arguably needs a Basic Income most?

Singapore, because she has the highest reserves per capita in the world, is in the top five for per capita income in the world, the fifth most expensive city in the world (The Economist) – and yet Singapore has no minimum wage, the greatest inequality amongst developed countries (Gini coefficient before government transfers), the biggest wage gap between the top and bottom percentiles, the lowest social welfare spending among developed countries, most expensive public housing in the world (price to income ratio), highest national pension contribution rates in the world (typically up to 37 percent of income), one of the most expensive electricity, water, public transport, public universities’ tuition fees, etc, in the world.

In addition to the above, Singapore has a unique fiscal policy (from a cash flow perspective) of limited spending on the nation’s pension scheme, public housing, and healthcare. However, the annual inflows exceed the outflows in each of these three areas, currently and historically.

Some recent statistics (April 2022) demonstrate that 10 percent of households cannot pay their water bills (media reports), and 10 percent of households do not have enough money to eat nutritionally (2019 pre-Covid-19, SMU-Lien Foundation Hunger Report 2019), etc.

So, perhaps in the final analysis – without Basic Income – many Singaporeans may have to continue to struggle to make ends meet. At the same time, Singapore has one of the highest per-capita suicide rates in the world, in spite of it being a criminal offense to attempt to try to kill oneself!

Singapore’s Reserves are estimated to be $1.97 trillion. If this is the case, perhaps it is time Singapore considers a basic income and shares this wealth with the people.

Written by: Leong Sze Hian

by Guest Contributor | Apr 9, 2022 | Opinion

14.5 million living in poverty

in the world’s fifth largest economy

until a global pandemic forced our chancellor

to spend £69 billion on a word

none of us had ever heard of.

Furlough showed universal basic income to be

a fundable possibility, at £67 billion net cost

paid for through reduced corporate tax breaks

and subsidies. Just 3.4 percent of GDP

to make absolute poverty extinct.

When the first unconditional money

hit mum’s bank account she cried

with eyes that could now see a future.

But trusting it took time. You’re not supposed to eat

normally just after a fast or you’ll be sick.

So we let relief drip into our days.

First in seconds, dancing round the kitchen

feeding shopping into starved cupboards

now bulging till their doors wouldn’t shut.

Then in minutes, a river that brought mum

home two full days a week. She began

helping me with my homework.

Grades went up. A well fed mind imagined

going to university, freed from the urgent need

to leave school early and start earning.

Knocks on the door brought not fear

but friends. Neighbours came to chat,

share ideas, our street hadn’t felt this alive

in years! Revitalised by breathing in

something other than stress and anxiety.

Minds to the right: tick

for smaller, simpler government; tick

for healthcare appointments reduced

8% by better physical and mental health; tick

for greater purchasing power from the ground up.

Minds to the left: tick

for greater community engagement; tick

for people secure enough to believe in a future; tick

for human ingenuity previously capped

by the poverty trap freed to help create

a society no longer chained to poor

wages for sourcing, making, selling poor

quality goods that return to poor

countries forced to burn, bury, breathe poor

quality air. Instead, the choice to say no

from a new sense of security, dignity, universality

we can do better.

Harula Ladd

by Guest Contributor | Mar 15, 2022 | Opinion

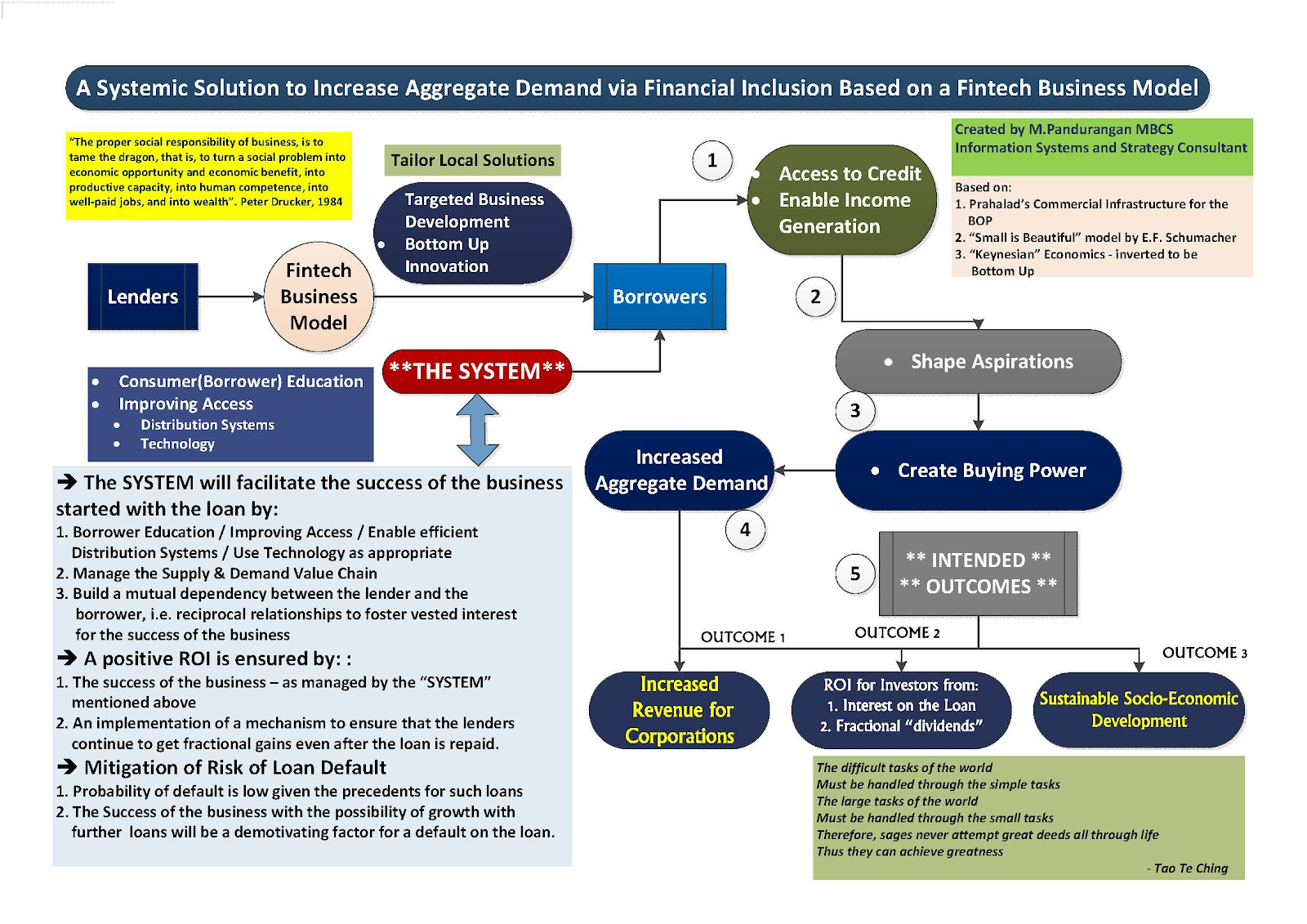

Universal Basic Income (UBI) takes care of sustenance needs, and SESED (Figure 1), can complement UBI to achieve poverty alleviation. This will be through a small business enterprise, whose success is facilitated by SESED given the peace of mind that UBI provides.

Figure 1 – A Systemic Ecosystem for Socio-Economic Development (SESED)

The SESED is a network of interconnected interdependent small businesses operated by people who are being helped to uplift themselves from poverty. These ventures are initially funded by microloans availed from sponsors, through Fintech companies.

The success of the business is ensured by a strategy of “benefits for all” modus operandi. Thus, the vested interests of all stakeholders are procured upfront.

The access to credit and the success of the enterprise evolves into income generation, from which aspirations, such as education for children, good health by proper nourishment and peace of mind, etc., are shaped.

These aspirations create buying power, now that the funds for these are available.

Though these ventures are small, the overall increased aggregate demand will create a whirlpool in the sluggish economy of the present, and result in a broader, vibrant, and sustainable one.

A key feature for the success of the venture is the “System”. This essentially facilitates the end-to-end process, and whose main responsibilities are:

- Borrower Education – Financial Literacy, Business Acumen, Skills Development, Psychological Interventions, etc.

- Enable access to credit via an efficient income distribution system; e.g., an interface with the Fintech company, manual distribution of funds.

- Manage the Supply and Demand value chain – e.g., suppliers must also be consumers, and vice-versa, of the products of the enterprises as appropriate. This could be along the lines of the Japanese innovation of “Keiretsu”.

- Foster a vested interest from the sponsor in the success of the enterprise for a win-win relationship.

- Tailor local solutions – i.e., targeted business development and bottom-up innovation; e.g., the product could be made available in a cheaper one-time use package, as well the regular one.

- Mitigate the risk of loan default.

- Deal with the idiosyncrasies of the society – e.g., in most 3rd world countries bribes are a norm, and extortions can be present as well.

The late Professor C. K. Prahalad, together with Professor Stuart L. Hart urged corporations to note “The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid”, and espoused “Eradicating Poverty Through Profits”.

It is thus that, not only is the primary outcome of poverty alleviation of UBI with SESED paramount, but they fall through benefits of 1) increased revenue for corporations due to the increased aggregate demand, and 2) the interest on the loans plus “fractional dividends” in the form of profits sharing for the sponsors, that stand out as unique, different and pragmatic in this model.

Thus, UBI with SESED will then be an “Auspicium Melioris Aevi” – an Augury of a Better Age.

M.Pandurangan

linkedin.com/in/mpandurangan

7 Mar 2022

References:

- Standing, Guy – “Basic Income: And How We Can Make It Happen”

- Ruskin, John – “Unto This Last”

- More, Thomas – “Utopia”

- Schumacher, E.F. – “Small is Beautiful”

- Prahalad, C. K. – “The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through Profits”

by Guest Contributor | Mar 15, 2022 | Opinion

On March 9, South Korea took to the polls for the 2022 Presidential Election. Former governor of Gyeonggi province, Lee Jae-myung of the ruling Democratic Party lost by a narrow margin of less than 0.7% to Yoon Suk-yeol from the People Power Party. This election outcome will likely stunt the development of basic income in the country.

As Guy Standing has written previously, this election in Korea is a vital one as Lee Jae-myung is a proponent of basic income. Prior to his candidacy, Lee served as mayor of Seongnam and subsequently governor of Gyeonggi, the province surrounding the capital city of Seoul. Among other initiatives, he famously launched the Gyeonggi Youth Basic Income (YBI) in 2019, providing valuable insights into how this idea might work in a highly developed country as well as an Asian economy. It is not so often that we see a major presidential candidate championing basic income at a national level (Andrew Yang dropped out of the race in 2020). Lee vowed to gradually implement a universal scheme in Korea, focusing on the youth and expanding to cover the entire population.

As the world’s 10th largest economy, a nationwide programme implemented in Korea could lead to tremendous progress in the discourse on basic income. With an advanced economic structure, high automation rate, and rising youth unemployment, Korea has the conditions of a postindustrial society in which a strong case for basic income could be built. Instead, such a prospect was overshadowed by more salient topics such as economic inequality, inter-Korea relations, and China’s influence. Gender equality and anti-feminism were at the forefront of the political debate, with Yoon pledging to abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family.

Dubbed the “unlikeable election” due to the prevalence of smearing campaigns, the presidential race was a very close one with neither candidate receiving majority support. Yoon garnered 48.56% of the votes nationwide, ahead of Lee’s 47.83%. A provincial breakdown of the election results reveals a highly divided country with democrat votes concentrated in the southwestern part of the country and conservatives in the east. Lee’s approval ratings in his own province seem to be falling – he barely received half of the votes in Gyeonggi this time, where he served as governor from 2018 to 2021. Now that Lee has resigned his governor seat and lost the presidential race, the cause for basic income in Korea will be affected to a certain extent.

This election outcome may not spell the end to basic income in Korea, however – outgoing president Moon Jae-in lost to Park Geun-hye in 2012, only to be elected as her successor five years later; moreover, a young Basic Income Party is seeking to bring this issue into the mainstream. The party fielded their own presidential candidate this year as well, critiquing Lee’s roadmap. Korea may not be the first country in the world to implement universal basic income just yet, but political tides could change and there is still room for this movement to grow.

On March 9 South Korea took to the polls for the 2022 Presidential Election. Former governor of Gyeonggi province, Lee Jae-myung of the ruling Democratic Party lost by a narrow margin of less than 0.7% to Yoon Suk-yeol from the People Power Party. This election outcome will likely stunt the development of basic income in the country.

As Guy Standing has written previously, this election in Korea is a vital one as Lee Jae-myung is a proponent of basic income. Prior to his candidacy, Lee served as mayor of Seongnam and subsequently governor of Gyeonggi, the province surrounding the capital city of Seoul. Among other initiatives, he famously launched the Gyeonggi Youth Basic Income (YBI) in 2019, which provides valuable insights into how this idea might work in a highly developed country as well as Asian economy. It is not so often that we see a major presidential candidate championing basic income at a national level (Andrew Yang dropped out of the race in 2020): Lee vowed to gradually implement a universal scheme in Korea, focusing on the youth and expanding to cover the entire population.

As the world’s 10th largest economy, a nationwide programme implemented in Korea could lead to tremendous progress in the discourse on basic income. With an advanced economic structure, high automation rate, and rising youth unemployment, Korea has the conditions of a postindustrial society in which a strong case for basic income could be built. Instead, such a prospect was overshadowed by more salient topics such as economic inequality, inter-Korea relations, and China’s influence. Gender equality and anti-feminism were at the forefront of the political debate, with Yoon pledging to abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family.

Dubbed the “unlikeable election” due to the prevalence of smearing campaigns, the presidential race was a very close one with neither candidate receiving majority support. Yoon garnered 48.56% of the votes nationwide, ahead of Lee’s 47.83%. A provincial breakdown of the election results reveals a highly divided country, with democrat votes concentrated in the southwestern part of the country and conservatives in the east. Lee’s approval ratings in his own province seem to be falling as well – he barely received half of the votes in Gyeonggi, where he served as governor from 2018 to 2021. Now that Lee has resigned his governor seat and lost the presidential race, the cause for basic income in Korea will be affected to a certain extent.

This election outcome may not spell the end to basic income in Korea, however – outgoing president Moon Jae-in lost to Park Geun-hye in 2012, only to be elected as her successor five years later. Moreover, a young Basic Income Party is seeking to bring this issue into the mainstream, fielding its own presidential candidate in the election this year as well. Korea may not be the first country in the world to implement universal basic income just yet, but political tides could change and there is still room for this movement to grow.

Truston Yu is a BIEN life member and former resident of Seoul, specializing in Southeast Asian studies including Korea-Southeast Asia relations. Their commentaries have been featured by numerous outlets including the Diplomat, the Jakarta Post and the Straits Times.

by Guy Standing | Jan 18, 2022 | Featured, Opinion

There are rare moments when a combination of threatening circumstances leads to a wonderful transformation that only a short time before would have been unimaginable. This year may be such a moment. The Republic of Korea could set an example to the world that would bring happiness to millions of Koreans, and to many more around the world.

The risks if politicians are too cautious are enormous. Before COVID-19, the global economy was already heading towards a crisis. For over three decades, more and more of the income and wealth were going to the owners of property, financial, physical, and “intellectual”. The commons, belonging to everybody, were being converted into the source of profits and rents. A new class, the precariat, was growing everywhere, suffering from multiple forms of insecurity, drifting deeper into debt. It was incredibly high debt – private, corporate, and public – that made the global economy uniquely fragile.

Meanwhile, the public across the world were realizing the threat posed by global warming and destruction of the environment. Nothing was being done. If that continues, life for our children and grandchildren will be impaired. And it is clear that mistreatment of nature has helped make this an era of pandemics. The COVID-19 outbreak is the sixth pandemic this century.

In these circumstances, policies that merely try to go back to the old normal will not work. We need a bold transformative vision, one of courage, one designed to give people basic economic and social security, one designed to make the economy work for society and every citizen, not just for the bankers and plutocracy, and one designed to revive the commons and our natural environment.

Jae-Myung Lee is campaigning for the Presidency in the March 2022 presidential election with an exciting and feasible strategy, based on a promise of a basic income for every Korean man and woman, paid equally, as a right, without conditions. It is affordable. What is important at this stage is not to set some ideal amount, but to be on the road towards living in a society in which everybody has enough on which to survive, even if they experience personal setbacks.

What makes the proposal for a basic income so profound is that Jae-Myung Lee has come from a humble background, knowing poverty and insecurity from his childhood. He understands two fundamentals. First, the income of every Korean is due to the efforts of all those Koreans who lived beforehand, and it is based on the commons, nature and resources that make up the country, which belong to all Koreans. Those who have gained from taking the commons, most of all, the land, owe it to all Koreans to share some of the gains. A modest Land Value Tax, or levy, is justifiable and fair, and should help fund the basic income.

He also understands that pollution and global warming must be combated by a carbon tax or eco-taxes. The rich cause more pollution than the poor, the poor experience the bad effects more than the rich, including bad health from exposure to poisonous air. So, the solution must include carbon taxes to discourage global warming and polluting activities. But by themselves such taxes would hit the poor harder, because the tax would amount to more of their income.

The only sensible solution is to guarantee that the revenue from eco-taxes will be recycled through a Commons Capital Fund to help pay for the basic income, as Carbon Dividends. The poor will gain, while society will be on the road to fighting global warming and ecological decay. A basic income will also encourage more care work and ecological work, rather than resource-depleting labor. It will stimulate the desirable form of economic growth.

The second fundamental Jae-Myung Lee and his advisers have understood is that basic security is essential for rational decision-making and mental health. There cannot be individual or societal resilience against pandemics or economic crises unless there is basic security, so that people can behave rationally rather than in desperation. Experiments have shown that a basic income improves mental health and the ability to make better decisions, for oneself, one’s family, and one’s community.

In the Korean edition of my book Plunder of the Commons, I paid respect to the ancient Korean ethos of hongik ingan, which helped found Korea in 2,333 BC. It expresses a historically-grounded wisdom that Koreans should be re-teaching the world in an era of self-centered individualism and consumption-driven “success”. It conveys the sense of not just sharing in benefits of production but sharing in the preservation and reproduction of a sense of community, our sense of participation and our relationships in and with nature. A basic income would pay respect to that ethos. Jae-Myung Lee should be commended for having pioneered it in Gyeonggi Province, and would set the country on a new progressive road if elected President on March 9.

——

A Korean translation of this article was published by Pressian – a political news website headquartered in Seoul, South Korea.

by Guest Contributor | Dec 3, 2021 | Opinion

In The Basic Income Engineer (not yet available in English, unfortunately), Marc de Basquiat invites us to embark upon a journey of discovery on the subject of Basic Income. Each chapter draws on a personal experience to illustrate his point and marks a milestone in his intellectual development. The author does not reveal much about his private life (we learn in passing that he has many children). However, this engineer by training and sensibility unabashedly shares the joys and frustrations that have punctuated his journey in search of solutions rather than truths.

He describes himself as a right-leaning by culture. His book reveals, on the contrary, a passionate person with a resolutely left-wing heart, underpinned by great scientific rigor. With his doctorate in economics acquired late in life, de Basquiat has been involved in all aspects of Basic Income research and advocacy: as a founder of the French Movement for a Basic Income (MFRB) and president of the Association pour l’Instauration d’un Revenu d’Existence (AIRE), he knows everyone.

Unlike most Basic Income theorists, who are little concerned with the practical side of things, de Basquiat distills the concept down to a simple formula and brings it to life by quantifying it: €500 per month minus 30% of income. It is this easy to understand and democratic (since it applies to everyone) formula that he successfully defends throughout his work.

The great strength of this book is that the reflection does not stop at the sole question of a Basic Income. Many other issues must be tackled simultaneously to ensure a better quality of life for all. De Basquiat is not a philosopher: so much the better! There are enough of them as it is who stir the economic pot without ever sitting down at the table!

For example, to ensure decent housing for all, he proposes a mechanism that would allow everyone to find housing in exchange for a quarter of their income. His best idea, in my opinion, is the proposal to levy a wealth tax of 0.1% per month (since life lasts about 1000 months) applied equally to the lords of the manor with assets worth 2 million € and to the owner of an old jalopy worth 1000 €. The first one pays 2000 € per month, the other just one euro. It’s an original and disarmingly simple concept that has enormous potential to transform mentalities and strengthen social solidarity. It is also a clever update of Thomas Paine’s Agrarian Justice, to which Basic Income supporters all claim allegiance, without taking full advantage of Paine’s message.

There are some proposals in the Universal Income Engineer that put me off. I can’t accept that an employer can purchase with his payroll contributions the right to direct his employees. A license to lead slaves cannot be bought. But de Basquiat is only describing how things are. Indeed, the power to manage employees is granted free of charge to anyone who sets himself up as a boss.

It is refreshing to see the socio–economic problems of our time treated in a global and integrated way, with rigour and without any ideological bias. It’s an engineering tour de force. And all this while raising a big family!