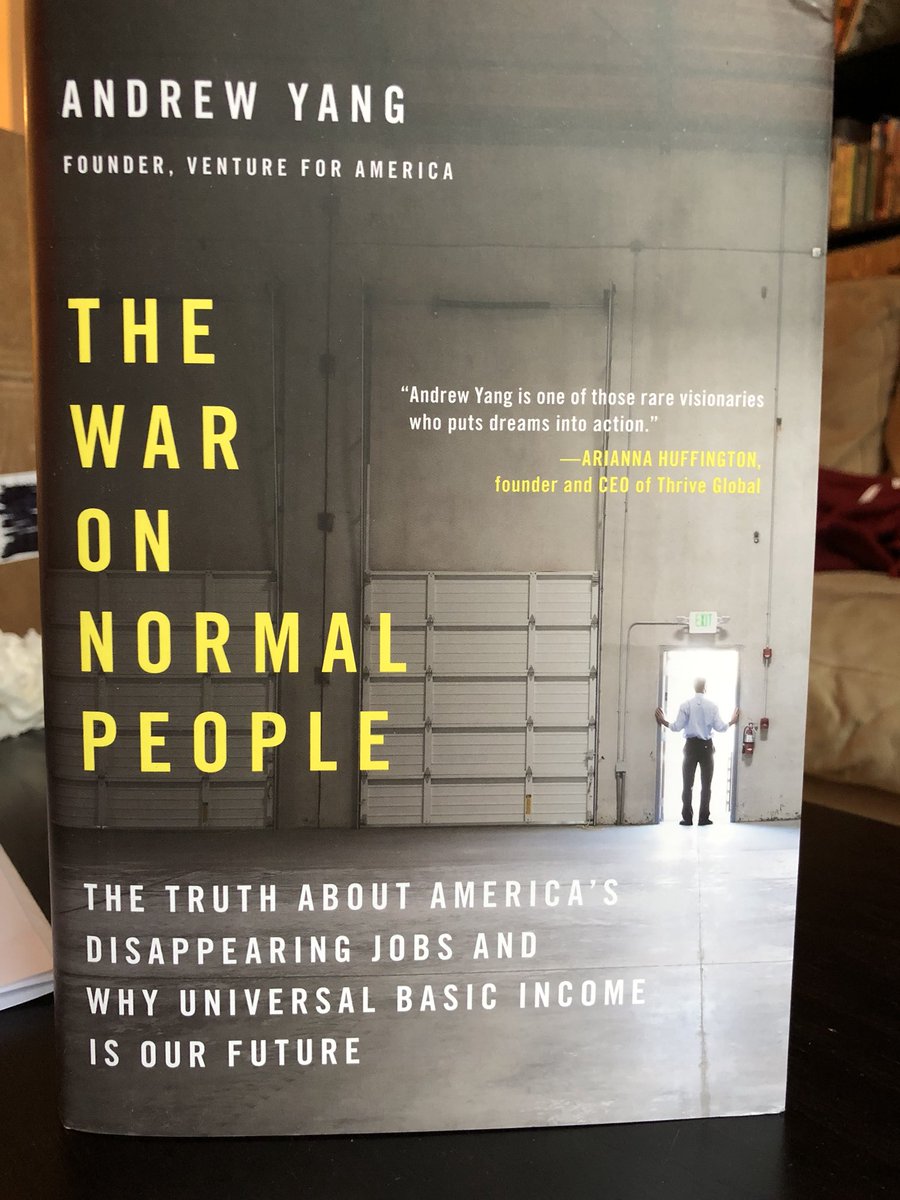

The War on Normal People: The Truth About America’s Disappearing Jobs and Why Universal Basic Income Is Our Future

By Andrew Yang, Hachette Books; 304 pages

Review by Karl Widerquist

NOTE: This article is reprinted from Delphi – Interdisciplinary Review of Emerging Technologies.

The original article and citation is:

Widerquist, K., “Book Review ∙ The War on Normal People: The Truth About America’s Disappearing Jobs and Why Universal Basic Income Is Our Future.” Delphi – Interdisciplinary Review of Emerging Technologies, Volume 2, Issue 1 (2019), 59 – 60

Andrew Yang is a technology entrepreneur who is taking three years away from his business to run for the Democratic nomination for president. His book, the War on Normal People, explains why Basic Income is the centerpiece of his platform.

This book review comes from the perspective of a political theorist who has been writing about Basic Income since the 1990s. Yang’s candidacy is one of many signs that the Basic Income movement is experiencing a substantial wave of support right now. But he is not necessarily the candidate of this extremely diverse movement. Basic Income comes in many forms and can go with almost any other set of policies. Whether any particular Basic Income supporter will also support Yang will depend on a host of other issues, but they should all take a serious look at his candidacy and his effort to make Basic Income an issue in the 2020 election.

This book communicates very clearly that Yang’s heart is in the right place. He’s not some narcissistic business owner running for president on the strength of his ego. He is very aware of the trail of luck and privilege that put him where he is today. He stresses that the American economy is not really the land of opportunity where anyone can make it if they try. It is full of injustice and unfairness. Most people will never get an opportunity to do what he did. And he points out clearly, the opportunities available to most normal people are shrinking.

Yet, Yang is no opponent of capitalism. He sees it as an incredibly productive and useful system in the right institutional setting, but the book’s title, The War on Normal People, typifies his perspective: even as our technology has made greater prosperity and opportunity possible, legal and institutional changes have reduce opportunities for all but the luckiest and most privileged Americans. The current generation of Americans is the first that can’t expect to improve substantially on the economic situation of their parents, and might well be doing worse.

Many factors have combined to cause this problem. Automation makes it possible to produce more goods with the same amount of labor, which ought to be good for everyone. But most people are dependent on labor for their income. They spend their lives building up skills that are suddenly outmoded by technology, forcing them into the already crowded lower end of the labor market.

Automation has produced enormous benefits for the people who own the machines and the people who lend the money to finance machines. And it’s created a few wonderful jobs for people who happen to have the right skills, but there are only so many of those wonderful jobs to go around, and not all of them have certain futures either.

For normal people automation has produced both lower wages and less certain employment.

Yang argues that the side effects of automation are only getting worse. Trucking companies are already in the process of replacing truck drivers with self-driving trucks, a direct threat to millions of drivers and an indirect threat to millions more people who work in supporting sectors, such as truck stops.

College tuition has gone up exponentially, and people have had to take out increasingly large loans to pay for it. According to Yang, people in their twenties and thirties today have so much educational debt that they are increasingly unable to buy homes, start businesses, or take advantage of their salaries.

The healthcare industry has also saddled people with increasing debt-a problem no other country imposes on its people. According to Yang, many Americans-even some who think they have good health insurance are vulnerable to bankruptcy if they have an accident or come down with a disease that isn’t adequately covered by whatever insurance they might have. It seems to be so easy for people to fall into bankruptcy these days, so it’s important that people budget their spending to make sure they are financially stable. However, if this can’t be done and people are on the verge of bankruptcy, it might be worth contacting a bankruptcy attorney San Diego, for example, to see if they can help people struggling with financial troubles.

One thing technology has given us is greater distraction. Yang argues that video games and social media are cheap, easily accessible, and built to draw you in. The decline in labor hours among young American men has been mirrored almost exactly by an increase in hours spent playing video games. Millions of American men in their 20s live with their parents and play video games 40 hours per week. In the short run, the instant satisfaction video games provide can make up for a lot of frustration and unhappiness in the rest of people’s lives. Whilst this may be true for some people, a lot of people around the world have actually been making money from these video games. By using platforms, like Twitch, people can stream themselves playing these games live. They can, eventually, start making money. To do this, people would just need a computer and then they would have to find out where to get ps2 roms. That would allow them to play those PlayStation games from their computer. They can then stream them live and make some money.

Yang points out many other serious problems that need to be fixed and that most American politicians are ignoring, but the one serious drawback of this book is that some readers might find it drawing their attention more to the severity of the problems Yang points out than to the promise of the solutions he suggests. This is unfortunate, because Yang is optimistic and offers serious and realistic solutions.

Any reader who feels despondent by Yang’s pull-no-punches statement of the problem, should reread the parts of the book stating Yang’s solutions, and concentrate on the ultimately optimistic, uplifting nature of his message.

Yang supports a host of policies that put him firmly in the most progressive wing of the Democratic Party. He wants single payer healthcare, also known as, Medicare for all, and an end to medical debt and bankruptcies. He wants campaign finance reform to get money fully out of politics. He wants free or cheap college tuition and an end to student debt.

But the centerpiece of his book, and what most separates him from other progressive Democrats, is his unequivocal support for Basic Income. Other progressive Democrats and even some mainstream Democrats have said favorable things about Basic Income. But even some of the most progressive Democratic elected officials, such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, have directly endorsed no more than the ‘exploration of it.

Yang wants a full, national Basic Income right away, and he wants it for good reasons. He doesn’t see it as a way to toss out a few tidbits to the poor but as part of the solution to the economic unfairness and injustice in the world today. Retraining will not cushion the disruptions caused by automation. Education will not end the stagnation (or reverse the decline) in wages that most normal people are experiencing. Yang wants to give them a boost and one that is not dependent on their employers.

He doesn’t make the mistake (common among tech entrepreneurs) of portraying Basic Income as something we’ll need someday when all labor is replaced by machines. He portrays it as something that’s needed right now and is perhaps already overdue after the last 40 years of automation-fueled economic growth have failed to deliver either higher pay or shorter working hours to normal people.

The Basic Income Yang begins with is too small, only $12,000 per year and not adequately covering single parents and their children (the poorest demographic group in the United States), but it’s a good start. That amount won’t end poverty, but it will be an enormous improvement for everyone living on the margins and a significant boost to the middle class. I had the chance to speak to Yang, and he told me he chose that plan because he needed something that was fully costed already. It’s just a start; he’s open to much more.

Yang’s book provides an excellent statement of the severe economic problems facing normal people in America right now, and it makes a compelling case that Basic Income is an essential part of the solution. Yang is a solid standard-bearer for the Basic Income movement. Whether he can bring Basic Income fully into the debate during the 2020 U.S. Presidential election remains to be seen.

In response to these excerpts…

“But he is not necessarily the candidate of this extremely diverse movement. Basic Income comes in many forms and can go with almost any other set of policies. Whether any particular Basic Income supporter will also support Yang will depend on a host of other issues…”

“The Basic Income Yang begins with is too small, only $12,000 per year and not adequately covering single parents and their children (the poorest demographic group in the United States), but it’s a good start…”

I beg to differ.

For the time being at least, Yang is THE BASIC INCOME CANDIDATE.

When Basic Income supporters get together, it’s easy to feel that basic income is inevitable. But this is not the case.

Basic Income is INCREDIBLY expensive.

This means that turning basic income into actual policy requires an INCREDIBLE amount of political will (for example, Yang proposes introducing and entirely new tax – VAT – to fund it)

People often say that basic income is supported by both the extreme left and the libertarian right, and the only people who don’t support it are the political center that hold power.

There’s a reason for that.

Basic Income is an incredibly expensive policy. For this reason, whenever most politicians find themselves in the driver’s seat and are left wondering how to fund it, they chicken out and look for a less costly policy solution.

Don’t be tempted by siren voices of rival candidates who say things like “basic income is worth exploring” or “I find basic income an interesting concept” such candidates are a complete waste of time and will NEVER undertake the required struggle to fund the policy.

If you care about basic income, you need to vote for the candidate with the most DETERMINATION to pass it.

That candidate is Yang. Maybe in the future other candidates may emerge, but for now, Yang is the only game in town. There’s no one else.

If UBI supporters don’t vote for candidates that strong support basic income because the basic income they propose is not “my kind of basic income” then basic income will never get implemented.

As to the second comment that $12,000 a year is too small, given that Yang plans to keep the existing welfare state in place along with all the required means-tested benefits – this comment is inappropriate as those with exceptional needs will retain access the the existing system that will give them access to exceptional means.

Anyone who doesn’t support Yang does not truly support UBI and is just another UBI tourist who thinks UBI is an “interesting idea worth looking into”

UBI is not particularly expensive.

Here’s why: https://basicincome.org/news/2017/05/real-cost-universal-basic-income/

Here’s an explanation how much it costs with a link to the research paper on which it’s based: https://basicincome.org/news/2017/05/real-cost-universal-basic-income/

BTW: I do support Yang.

John McCone,

[“…Anyone who doesn’t support Yang does not truly support UBI …]

Voting for Yang just because the words “UBI” exist in his platform is quite an extraordinary thinking

I am willing to bet that the positive effects of Yang’s version of UBI will not last longer than one manufacturing cycle after implementation.

Yang’s version of UBI is a consumption-based corporatist-approved UBI which does not affect extreme poverty in a meaningful way, because it is based on the belief that, ‘The rich always spend a lot … and it would be sufficient to trickle-down to the rest of us as UBI as long as we tax their consumption.’

Yang’s freedom dividend just transfers funds from the companies that get taxed by him to the owners of businesses which provide the most essential goods and services to the humans …

The people will remain poor after a very short period of positive effect.

Why?

Because, Milton Friedman said that all agents in the society are driven by self-interest . It means, that the moment you give the humans some disposable Wealth ($1000 or whatever) then every other agent (business) on the free market will attempt to harvest that disposable wealth. … and guess what, there is spending which the humans must have inevitably which gives certain businesses the edge when it comes to harvesting that extra disposable Wealth from the humans.

So, all them businesses would have to do is to re-package their product and to put a new price tag on it and the extra disposable income is theirs because the humans must spend on those essential goods and services.

You might argue that the market competition will keep the prices down…but there isn’t real market competition in the presence of Extreme Concentration of Wealth. Also, the free market inevitably leads to extreme concertation of Wealth therefore any existing real competition can not be sustained indefinitely.

I would be curious to hear any UBI proposal that has a higher equivalent starting value than Yang’s $1,000 a month, by any pro-UBI politician or party manifesto, anywhere in the world.

What struck me about Yang’s proposal initially was actually how high it was compared to every other proposal I’ve heard that has a real chance of being implemented. I enjoyed the article, but can you cite some sources that shows that Yang’s UBI is comparatively “too small”? I basically agree with John McCone’s critique.

A lot of UBI advocates have made much larger proposals. The Swiss Citizens Initiative was twice as high. That was mainstream politics, though not in a party manifesto. I bet some small parties have larger versions.

Some of the ways in which Yang’s proposal is small are not readily apparent. It’s only for adults. So, a single parent with two kids gets the equivalent of $4000 for each member of the household. That’s pretty darn small. Another way it’s small is that you have to subtract the VAT. Yang assumes business pay for the VAT, but if they pass it on to citizens. The value of your $1000 monthly Freedom Dividend goes down to $888.88.

It’s a start. It’s only a start.

But, of course, we badly need a start.

I wasn’t aware of the Swiss proposal. Thanks.

Agreed, the most important thing IMO is to get the ball rolling.

It feels to me, Professor Karl Widerquist is extremely generous towards Yang. So I will challenge that generosity. We desperately need UBI but not the kind of fake UBI Yang stands for.

I believe Yang’s version of UBI is a consumption-based UBI. It is evident from the sources of funding listed on Yang’s candidacy web-page:

* VAT is always paid by the end-consumer. (VAT is a consumption-tax which shortens the chain of re-sale between manufacturer and the end consumer)

* Carbon-tax is a consumption tax which is supposed to repair damage to the climate, not to feed the people.

* The current Welfare system also pays for Yang’s fake UBI (and still … the Wealth of the wealthy is intact)

and finally…

* ‘Hope’ is what pays for Yang’s UBI “scam” …. the hope that the economy will grow.

Furthermore , Yang talks about the “robots” … but he does not forget that they are Wealth too, therefore, no wonder, they are not listed as the source for UBI on Yang’s candidacy web page.

(The Yang logic comes down to, I’ll own the “robots” that make me whatever I need but the rest of you would get UBI only if you consume, which means you must order from me whatever I tell my robots to make for you. LOL)

Yang’s corporatist logic in a nutshell is, ‘The rich always spend…. and it will trickle-down to the rest of us as UBI as long as we tax their consumption.’

Yang’s approach quite resembles the well known unsuccessful idea that, ‘The rich always invest and it trickles-down to the rest of us.’

The truth is, ‘The rich own, they are neither required to invest or spend.’

I believe, Yang fails to understand that the implementation of UBI can not be Income-based or consumption-based or a resource-based (Alaska) or cow-manure-based or human-sacrifice-based …. or whatever-based …. except …

… UBI must always be Control-and-Ownership-of-Wealth-based.

When implementing UBI, any entity (private or public, biological or artificial, constructed or emergent) within the society must pay a tax for the ownership of wealth which they have or command …. which then funds the real UBI for the citizens only.

If Wealth-based UBI is implemented correctly then, ‘The higher UBI is, less billionaires/multimillionaires there are compared to the poor…. and nobody lives in poverty compared to the billionaires.’!

*****

Yes, we need a start but we need the correct type of start I’ll describe here:

First, let’s start by restricting the borders for movement of Wealth outwards and people inwards (UBI depends on the available Wealth and the amount of people)

Second, the polit-economic landscape (economy, taxation ,etc.) has complex hierarchies and feedback loops which will have to be accounted for as they are exposed during the implementation of the real UBI.

Therefore , let’s introduce immediate UBI of $1 per week (to work out the way it reaches the people), and then let’s start cranking it up every month until … (very important) … the increase in Wealth disparity stops permanently.

The implementation process must be done in this way to provide time for achieving the real structure of funding for the real UBI while navigating and shaping the polit-economic landscape to provide that funding.

(I could place a bet that there will be a civil war or, at least, massive disturbances before a permanent stop is put to the increase in Wealth disparity. It would be “fun” watching the politicians and the economists and the Wealth owners trying to figure out how to source the funds for UBI so that the Wealth disparity stops and consequently gets reduced.

It would be epic…. and very doable within 4 years ….. just keep cranking up the UBI each month for as long as it takes.) lol

They will try every trick (like Yang does) but eventually they will have to get to a real Wealth-based UBI because none other types of UBI stops permanently the increase in Wealth disparity.

Third, We can then decide if we want to crank up the UBI a bit more until the Wealth disparity is sufficiently reduced to eradicate poverty.

It is so simple, but Yang does not want that, because he deceives us knowingly or unknowingly..

Overall the book talk-the-talk but does not deliver on the solution.

The author of the book, Yang works well for the popularisation of the UBI and I hope he will stay in the presidential candidate race for a bit longer however the longer he stays in the race more misconception he creates about the UBI funding.

I am sorry I can not be more generos towards Yang’s version of corporation-approved consumption-based UBI.

Please see this contribution on how to pay for UBI

https://governingtaxfree.wordpress.com/2018/06/11/how-to-pay-for-universal-basic-income/

Thank you

Yang’s consumption-based UBI is a fake UBI !

Basically, if UBI is paid in beer, then should UBI be raised from the beer in my bottle or should UBI be raised from the beer I pour out of the bottle?

Yang’s UBI is raised from the beer I pour out of the bottle … which makes it ‘a fake UBI’ since if nobody is drinking then you do not get to receive any beer as UBI and you die from thirst.

Do you get it? The Yang’s UBI is created by a corporate type of thinkers.

If you do not believe me then go on Yang’s page and look at how he will fund his UBI … it is from consumption (VAT, carbon tax), the current welfare system and the “hope” that the economy will grow LOL … fake to the bone.

Amazing how we never debate how to fund the Pentagon, or pay for the bombs, or all the money that went to bail out the banks that caused the debacle of 2009.