(This article originally appeared on Medium)

It will be difficult to fully convey what I witnessed, as it is virtually impossible to transfer through mere words, the levels of emotion and passion that were originally attached to those words. This is in itself a key point to understand. This was not just some academic conference of raw numbers and dry analysis and discussion. This was a group of people coming together from a variety of backgrounds and perspectives, all projecting a level of passion far beyond economics and academia, and all present to discuss the idea of simply giving people money to meet their basic needs.

What happened was essentially a drawing of a line in our societal sand.

This far and no further.

Having read James Madison’s notes from the Constitutional Convention, I couldn’t help but feel to some degree a little of what he must have felt then, a sense that what I was attempting to faithfully record was somehow potentially historic in precedent. Speaking to others, this feeling of something outside the normal experience did seem mostly unanimous among those who have been to any of the previous thirteen NABIG Congresses. There was something in the air in this one that was different than all before. This one involved fires that had been lit within people.

With that said, the following is a summary in a more readily shareable form, so as to better enable the sharing with others of what felt like the more powerful sentiments made and discussions explored over the course of the Congress.

Thursday, February 26, 2015

Opening Discussion: “New Possibilities for the Basic Income Movement”: FULL NOTES | NO VIDEO

This first meeting involved all of us sitting around the edge of a room and many having something to share with the rest.

Mimi Abramovitz shared how as a child raised in a family with little outcome, it was the very fear of poverty she remembered most, and seemed to have the greatest effect on her mother.

Francis Fox Piven shared how our growing inequality is having an adverse effect on our very values as a society. We look at each other differently. We care less, and we resent more.

Willie Baptist of the National Welfare Rights Union shared how technological unemployment is redefining the value of human life in the eyes of those who no longer require human labor.

Mathew Schmid, filmmaker working on a basic income documentary, shared how work and income are actually in no way related. Some work for no income, and some get income for no work.

Mathew went on to discuss the connection between a basic income and our challenge to take on climate change. As long as too many have too little, taking on humanity’s greatest long-term concern will be outweighed by our short-term concern — survival.

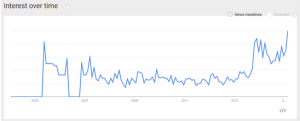

Jason Burke Murphy of USBIG shared how he has seen a sea change in the awareness of people of the idea of basic income. No longer is everyone new to the concept. The idea is spreading, and spreading fast.

Alanna Hartzok, 2014 Democratic nominee for Congress in Pennsylvania shared how commonwealth dividends are a right, and how kids will grow up knowing they are their birthright as seen in Alaska.

Felix Coeln of the Pirate Party in Germany further stressed the importance of a basic income as a human right of everyone, everywhere, without any conditions. This is paramount to the idea and to its success.

All of the above took place in a room at the Long Island City Art Center where many of us present met for the first time. As discussion circled the room, introductions were made and notes were taken. Priorities were stressed and issues were raised. By the time it was over, we were all more than ready for the weekend ahead and the discussions still to follow.

Friday, February 27, 2015

Session 1: “Technological Unemployment and the Basic Income Guarantee” with Marshall Brain: VIDEO | FULL NOTES

Marshall Brain, founder of Howstuffworks.com, and author of Manna and Robotic Nation, began his presentation with this short video.

Marshall then asked us to put ourselves in the space shoes of a being from another planet, and describe what we see when we look at a planet that allows the above massive concentration of wealth while half the planet exists on less than $2 per day. What do we see when we observe 10,000 nuclear missiles, environmental destruction, mass extinction of species, prisons, racism, religious strife, war, disease, nations, and mass surveillance?

“Humans appear to be insane.”

If we were actually sane, wouldn’t we instead spend trillions of dollars curing diseases and ending poverty, instead of investing in endless wars?

If we were actually sane, wouldn’t we end our massive concentration of wealth where less than 100 human beings have BILLIONS while BILLIONS starve?

Where are we going as we automate away our labor and advance our way to creating artificial intelligence? What is our end point? Is it perpetual vacation and some relative heaven on Earth? Or is it something else in a collective refusal to provide an unconditional income to every human being?

Are we going to begin making our technology work for us? Or are we going to continue allowing our own technology to work against most of us but a special few?

(For more, “The Second Intelligent Species How Humans Will Become as Irrelevant as Cockroaches” by Marshall Brain is now available in full online.)

Session 2: “To Have and Have Not in the Twenty-First Century Economy” with Michael Lewis, Oliver Heydorn, and Karl Widerquist: VIDEO | FULL NOTES

Michael Lewis focused on our distinction between who is deserving of help, and who is undeserving of help. Here we have Social Security, disability, welfare, and perhaps drawing such distinctions in the first place was never the right thing to do? And perhaps it’s now less and less right as time goes on because in a time of increasing inequality, we need to recognize that no one chooses to be born into their environments. No one chooses their genes or their homes or their parents. So right there we already have a problem with a false dichotomy between the ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving.’

If there are no choices being made in our circumstances we are born into, how can anyone be considered worthy or unworthy of living? How are some worthy of basic economic security and liberty, while others aren’t? Such ideas should be entirely universal and nothing less. Period.

Oliver Heydorn went on to discuss the idea of Social Credit and how although not qualifying as a basic income, it would accomplish many of the same goals.

Karl Widerquist spoke of what he considers our major incentive problem, and it’s not that people have no incentive to work, it’s that work has no incentive to pay good wages.

“If there is a job that someone doesn’t want, why do we assume they won’t do the job, and not that the employer won’t offer the right wage?” — Karl Widerquist

For Karl, the idea of basic income is that no one should be destitute. It’s not about luxuries. It’s about making sure people can survive. How crazy is it that we don’t even starve murderers to death, and yet we have that severe of penalty for not working in the labor market?

Karl Widerquist sees access to basic resources as a right that is currently being prevented, and no one has that right.

“No one has the right to come between an individual and the resources they need to survive.” — Karl Widerquist

This idea that a basic income is something for nothing is completely the opposite of what we need to recognize. Because every piece of man-made property in existence is made out of natural resources that were once freely available to everyone, we have taken these resources away without compensation, and decreased everyone’s freedom in the process.

We need to get beyond this idea of a “work ethic.” It’s not even something we’ve ever had. What we need is what work provides, not work itself, and certainly not jobs.

What we really need is money, because money is what we use to gain access to resources. And as long as that’s true, because everyone requires a minimum access to resources to survive, we require a minimum amount of money to survive.

And that money we need to survive, is compensation for the loss of access to universally shared natural resources we once had.

I enjoyed a few comments in particular during this Q & A:

“The jobs that no one would want to do would be the jobs that are well paid. And the jobs that everyone wants to do would pay less. And that’s the way things should be.”

“Land is the basis for life. You can own land and building something on it. But then you should pay rent to the commons.”

Session 3: “Exploitation and the Basic Income Guarantee” with Michael W. Howard, Brent Ranalli, and Ashley Engel: VIDEO | FULL NOTES

Michael Howard discussed basic income [.doc] as perhaps Karl Marx would see it, asking if Marx would still view labor as exploited if all labor had a basic income? He also wondered if perhaps people don’t have a right to the natural resources they have no independent interest in, as in the case of “Mr. Pickles”, where one man diverted a stream of water away from the town of Bradford for his own use.

“Unconditional Basic Income enables voluntary cooperation among free and equal citizens.” — Michael W. Howard

Brent Ranalli discussed the Townsend Plan Movement [.docx] and what there is for supporters of basic income to learn from that bit of history where so many people came together around the idea of a universal pension for seniors, prior to (and greatly inspiring) the enactment of Social Security.

Townsend Lessons:

- Harness existing discontent like child poverty and student debt.

- Harness the middle class. Do not alienate them.

- Work across party lines and avoid framing the issue in a way that only reaches the right or the left. Framing UBI as an anti-poverty initiative could fail whereas framing as a universal right could succeed.

- Recruit the “biographically available”, those with the most time and freedom to engage in a movement like students and seniors.

- Appeal to both self-interest and altruism, like how the Tea Party does with tax cuts. Basic income supporters can do the same by talking about bolstering the economy and providing more collective ownership of commons.

- A good plan for financing basic income is required. Taxes may be unpopular, but people loved the Townsend plan despite its new transaction tax. In turn, basic income could become popular through just the idea of the payments themselves, and the funding method could be secondary to growing popularity as a method can always be devised to achieve it after the idea is popular and demanded.

Ashley Engel then framed basic income through the perspective of its potential effects on human trafficking [.docx]. Describing the present liberal approach as greatly flawed in not reducing human trafficking, she went on to say that as long as the root cause of human trafficking isn’t addressed, it will only continue to grow. To address this root cause, we must use an economic lens, and we must recognize that it is economic insecurity that makes people vulnerable to human trafficking. Unless we prevent that insecurity, we will never prevent ongoing human slavery.

Session 5 (Session 4 was an extended lunch break): “The Basic Income Guarantee and Work” with Jim Bryan, Seán Healy, and James Green-Armytage: VIDEO | FULL NOTES

Jim Bryan started out this session by hitting us with our growing inequality and the effect its having on generational mobility. Looking at generational elasticity, we measure Denmark as being best, along with Finland, Norway, and Sweden. In turn, the worst elasticity is now found in the USA, the UK, and Italy, where circumstances of birth are far more likely to stick than anywhere else in the developed world.

Basic income is an effective means of at least partially addressing this shrinking elasticity, in its direct effect on reducing inequality, and its side effect of increasing opportunities.

“You could get a whole lot more people on board to make opportunities more equal instead of incomes more equal.” — Jim Bryan

Sean Healy then came up to present what might possibly be for those who believe in full employment, the final nails in that bygone coffin. With a global unemployment forecast set to continue rising to 220 million and beyond, unemployment is unavoidable without massive job creation, the likes of which are statistically unimaginable.

“We would need an estimated net gain of 1 billion jobs if we are to keep unemployment where it is today over the next 12 years.” — Sean Healy

Or in other words…

This is damning research based on low population projections. If actual population growth is even higher, then matters become even worse.

James Green-Armytage focused on a job guarantee and its potential sustainability. He also likes the idea of a job guarantee where anyone who wants a job can get one, combined with a Georgist model of income shares of the commons, or in other words a Land-Value Tax dividend version of basic income. His hope is that such a model would lead to people voting with their feet, working in jobs that need to be done, and not working in jobs that don’t. Thanks to a separate income stream independent of work, people could effectively vote for wanted private and public businesses by giving them their dollars.

During the Q&A session, Sean provided a very telling example of our blinding obsession with jobs, when he shared how a published poet he knew came around to the idea of basic income, only after it was directly pointed out that writing poetry would become an actual option for everyone, including him. Until it was directly pointed out, he just couldn’t see it.

Session 6: “Confronting Poverty, Race, and Women: Changing the Dynamics by Bringing More People and Voices to the Table”: VIDEO | FULL NOTES

In a double-panel Ann Withorn referred to as practically “the Oscars of welfare rights advocates”, I witnessed what was in my opinion, the most emotionally moving discussions of the entire weekend. The voices we heard from were the voices of those who have been fighting for welfare rights for years and even decades. These were voices from “boots on the ground”, who have experienced those in poverty face to face, and have yet to ever see victory in the “War on Poverty.”

Frances Fox Piven talked strategy. She talked about the need for more than just an idea.

“A lot of people who haven’t been bruised by movement work, think a good idea is all you need.”

She talked about the uphill battle ahead against powerful people who are very good at telling people what they want to hear.

“We have enemies out there, and they too can whisper magic words into the public ear.”

She spoke of a misinformed public who are no accident, and the difficulty that lies ahead in reaching through to them.

“It isn’t public opinion that shapes policy, it’s powerful private interest groups that shape policy. These changes around us aren’t happening because people haven’t heard about basic income. It’s happening because purposely people are being misinformed.”

To actually achieve basic income, will involve breaking through the walls constructed around it and other good ideas. And to do this, will require the efforts of those willing to cause trouble, and the alignment of interests with others willing to do so.

Diane Dujon then shared a great many impassioned thoughts from her long history of battling for the rights of others. She feels a major lasting obstacle is the long-held and continuing public delusion that people are in a “middle class” when they just aren’t. This delusion prevents people from fighting for the rights of the poor because they define themselves as not-poor, even when they are poor. And the last word to describe poor people is lazy.

If we allow ourselves to see ourselves as separate classes of people, with some being deserving and others not being deserving, and we don’t stand up for the rights of those we feel are different, it will come back to us, as it always does.

“This country is getting ridiculous, and we need to start realizing what’s happening to ALL of us.” — Diane Dujon

Diane also mentioned how she helped create a tool for the poor to better enable them to successfully apply for assistance programs, and the result was that the government then just changed the rules. Bureaucrats have no real interest in distributing money. Their interest lies in not distributing it.

Marian Kramer and Sylvia Orduno of the Michigan Welfare Rights Organization talked about the battle against Bill Clinton and his dismantling of the old welfare system and how these battles continue today where the stakes are even higher, with people literally dying on the steps of churches.

Powerful interests find it very much in their interests to keep the working class solidly divided, and these divisions weaken the attempts to unite in solidarity for universal rights.

But these divisions have the potential to be healed through the idea of basic income. It’s an idea that can unite everyone across so many disparate groups, because the idea cuts across so many artificial divisions.

Through all of what lies ahead, a key point to remember is the “Why.” It’s easy in some ways to mobilize great numbers around some cause. But it’s harder and more important to make sure we know why we are there.

Session 7: “Basic Income and Welfare Rights for All: Out of the Past and into the Future”: VIDEO | FULL NOTES

This session was basically a continuation of Session 6, with more to hear from those from the National Welfare Rights Union and MWRO.

Mary Bricker-Jenkins started by focusing on the effects of technology on the common welfare and how the ability of jobs to provide financial security has been eroding for decades.

“Something has happened with the fundamental ways we produce goods and services for survival.” — Mary Bricker-Jenkins

Mary has personally seen what has happened in Detroit and what is continuing to happen as they now even fight for their right to water.

“For Detroit, specifically what happened was the microchip. In the 1970s the first robot appeared on the factory floor in Detroit, Michigan. It heralded the fundamental shift in the way we distribute goods in the world economy. Now the fundamental contract is ruptured. We simply don’t need the surplus labor to produce what we need. What we were dealing with was a surplus. What we’re now dealing with is the superfluous.” — Mary Bricker-Jenkins

People are beginning to be seen as no longer necessary. Can’t find a job? Too bad. Your life has no value anymore. What right to water? If you can’t pay for water by having a job that doesn’t exist, then feel free to die. That’s where we are right now. That’s the future we have to look forward to as technology continues to massively disrupt the labor market and how we go about determining who gets sufficient income for survival and who doesn’t.

Without basic income, people are contributing to their own demise, instead of their own freedom.

Marian Kramer continued this discussion of technology’s effects on jobs and the distribution of income.

“Technology has began to play a hell of a role in production here. Where once the robots enhanced the workers to work, now in a complete turnaround, the workers are enhancing the robots to work. More and more workers will be displaced by technology.” — Marian Kramer

Unbeknownst to many, Detroit shut off the water to 30,000 people. Considering how survival without water is only possible for a few days, it can be said that there are those in Detroit who no longer care whether 30,000 of their poorest residents live or die.

Sylvia Orduno put out a call for writers to get the message out and provide a bridge around those ignoring what’s happening in Detroit and elsewhere and what people need to know about what’s happening.

“The academic work is not being bridged on the ground with movement work. There needs to be mutual respect between those on the ground and those writing.” — Sylvia Orduno

She also warned that part of doing actual movement work on the ground is being shutdown over and over again. One must get used to this, and continue on regardless.

Willie Baptist then opened by quoting the Declaration of Independence and adding, “There’s no reason in the world, in the richest country in the world, that we go hungry, and without water.”

We have the unalienable right to life, and this right includes access to food and water. Government was instituted to secure the right to life, and not only has it failed, it continues to fail to an increasing degree.

A new social movement for basic income is needed and it will take stages. It will be achieved one step at a time, and will require those willing to see it through all the way to the end and beyond.

To achieve basic income, supporters will need to develop sophistication that matches the sophistication of who and what we’re dealing with. This needs to be done, because the fight for basic income is more than just the fight. It’s about winning the fight.

“This is not about fighting the good fight. This is about fighting and winning.” — Willie Baptist

Willie stressed the importance in getting people to understand that when people are poor, it is the result of the system itself, not any perceived individual failings. He also stressed the importance of the universality of basic income, and how it’s not about helping only those in poverty, but everyone with no one excluded.

The struggle for the right of all of us to live, for all of us to have access to what is required to meet our most basic needs for life, is a universal struggle yet to be won. But it must be won.

According to Willie, we need to use our writing and intellect. We need to create the same conditions as were created over a century ago, where slaves began to run away. We need to create the conditions where the poor no longer accept they are poor for any other reason than the system itself is forcing it upon them. We need to create the conditions where what we see around us everyday is no longer acceptable, because it’s not acceptable.

We must never forget that what needs to be done is more than an idea. It is a new way of thinking, and to achieve it, people must be moved, or the only thing basic income will ever be, is just another good idea.

“We can have the greatest ideas in the world, but if we can’t move people’s thinking… then that’s all they’ll ever be” — Willie Baptist

Saturday, February 28, 2015

Session 8: “The BIG Implementation Questions”: VIDEOS: 1,2 | FULL NOTES

Sid Frankel discussed strategies of basic income implementation. Recognizing the attractiveness of rolling existing programs into a BIG, he recommended not overplaying this fact. It would be better to avoid talking about eliminating everything, and also to avoid additional taxes that do not bring immediate benefit in return.

According to Sid, it might be better to focus on Alaska-style dividends that provide people extra money without increases in taxes. In addition, the size of any program needs to be neither too small nor too large to gain the widest level of support.

Jurgen De Wispelaere followed by inviting us to get serious about basic income and the obstacles it would have in the existing programs it wishes to at least partially or mostly eliminate. Vested interests will be a direct challenge, both from the administration side, and from the recipient side who will be wary of any changes out of fear of being worse off.

So how do we go about turning the required political levers to effect change? Jurgen doesn’t believe something like justice is enough. What is required is something that translates into creating the largest constituency.

“Basic income is a society-wide improvement, but it does not mean that everyone becomes constituents.” — Jurgen De Wispelaere

If the size of basic income is too small, too few people will feel they will directly benefit enough. So it must be large enough for most people to want.

Additionally, because the idea of security polls better than the idea of redistribution, perhaps it would be more effective to promote basic income as a means of better social security for all in a time where technology and globalization is eroding security as we know it.

Session 9: “The Politics of BIG, Part 1: the political movement”: VIDEO | FULL NOTES

Jason Burke Murphy made the point that some people are extremely adamant about what does or does not count as an acceptable basic income, both in amount and implementation details. In this regard, we need to consider how important these artificially drawn lines are, especially if we also consider how any basic income, no matter how partial, has the ability to grow in time into one we each may fully approve.

We should thus avoid letting our “perfect” basic incomes get in the way of “imperfect” basic incomes, or even partial ones like the Alaska dividend or a universal child allowance. This is foot-in-the-door logic.

“A bad tax regime is better with a basic income. A bad government is not as bad with a basic income. A bad family will not have as bad a time with a basic income. BIG is a good proposal even where the project is bad.” — Jason Burke Murphy

In essence, we must not let perfect be the enemy of good. Any amount of money given unconditionally to all, or even some, is better than no money. And once people start receiving some money on a regular basis with no conditions, this will only grow — not shrink — support for basic income.

“Basic income can replace the welfare state in stages very elegantly. Seeing a less bureaucratic solution gets people posing the right questions.” — Jason Burke Murphy

Jason also mentioned the interesting news that a rape shelter in Vancouver is supporting basic income as a means of reducing sexual assaults, through the reduction of conditions that lead to them. These kinds of connections need to be made within other organizations, so potential allies can see basic income helps their cause too.

Jonathan Brun then discussed the necessary steps to achieving basic income over the long road ahead [.pdf].

“I do think basic income is possible in our lifetime… but it will be extraordinarily difficult.” — Jonathan Brun

Five key elements are required in the coming years:

- Building an identity

- Getting organized

- Spreading the message

- Growing a movement

- Exerting pressure

Achieving these will require being able to describe the idea within 10 seconds, starting small but being able to scale big (like Tupperware parties in the past), creating conflict, achieving media coups, periodic small victories, and non-violent tactics.

Felix Coeln then discussed how basic income is part of the Pirate Party platform and how that came to be. The idea of a basic income is in full agreement with the Pirate Party core principle of defending the free flow of ideas, knowledge, and culture.

Felix also stressed the importance of understanding that our politicians are our representatives. We are the ones that hold the power, not them. So if we want something, it is ultimately up to us to make it so.

Felix ended with the idea that we have the right of secure existence and participation in society, and we should secure that right with basic income.

In the Q&A it was mentioned how both Neil deGrasse Tyson and Bill Nye support Alaska-style resource dividends, and it would be valuable to leverage bits of trivia like this in the form of easily shareable images to reach more people. Using humor in such pro-UBI images would be even better.

Also, it was Switzerland who got the world talking about basic income with their successful signature gathering campaign for their initiative and their dump truck full of gold coins, so it would be smart to attempt to duplicate this success with more tangible victories and visuals the media love.

“We have the right of secure existence and participation in society, and we should secure that right with basic income.”

Session 10: “The Politics of BIG, part 2: the basic income guarantee and electoral politics”: VIDEO | FULL NOTES

Ian Schlakman discussed how as a Congressional candidate for the Green Party in Maryland, it wasn’t until he made basic income a key part of his campaign that people really started to show interest. And that it was framing basic income as “Social Security for All” that seemed to aid best in people understanding what basic income is.

It is this idea of security that people understand and feel they are losing. Every year, we all grow less secure, as the employment market transforms, and yet our safety nets are actually being reduced and outright dismantled.

“The current welfare state has been tattered. Absolutely tattered. It’s not a welfare state. There’s no welfare. It’s all temporary assistance.” — Ian Schlakman

Perhaps by focusing on the security aspect of basic income, more people will embrace it more widely, regardless of party affiliation.

Alanna Hartzok then shared her experience as a Congressional candidate for the Democratic Party in Pennsylvania. She received 36.52% of the vote with only around $22,800 and an all-volunteer campaign on a message of building a movement for progress built on the idea of “economic democracy” through Alaska-style dividends using land rent and other common resource rents.

No one created land. Everyone can only build on land, and the value of land only increases because of who and what’s around it. Because of this, the unimproved value of the land itself is commonwealth, owned by all and thus should be shared by all. The sharing of land rent is not a new idea, and like basic income itself, its support also covers the spectrum — from Adam Smith to Karl Marx.

“Every land owner owes to the community a ground rent for the land that he holds.” — Thomas Paine

Henry George was the strongest advocate for a Land Value Tax and it’s something that is even more important now than it was during his lifetime. In the past 100 years, land rent has grown from 8% t0 26%, and our metropolitan areas are now virtual gold mines for landowners.

It is vital we begin to end this land exploitation, and begin to share in the values of land no one person creates. And we can do this through dividends from land value tax revenue. According to Alanna, LVT would also function as a reduction of taxes for most, just as in Pennsylvania where 85% of land owners pay less by their taxing the value of land and not buildings.

Eduardo Suplicy next spoke about his experience as a Senator of Brazil [.doc] in getting the first basic income law in the world passed in Brazil, which has yet to actually implement anything more than its Bolsa Familia program as a step along the way. Signed into law in 2004, for 11 years now it has been up to the President of Brazil to roll out a full basic income to the country, but so far this has not happened. Since June of 2013, Eduardo has written letter after letter to the President to execute their basic income law. It is unknown when it will finally happen but Eduardo will continue doing everything he can to make it happen.

“We need to have a public conversation about private property and public property. Once people understand the idea of the commons, they will accept the idea of sharing commons dividends.”

Session 11: “The Basic Income Guarantee in the Twenty-First Century Political Economy”: VIDEO | FULL NOTES

Bill DiFazio spoke about his and Stanley Aranowitz’s book, “The Jobless Future”, and how they’ve updated it. Published in 1994 originally, it is remarkable how accurate its predictions have been in describing a future where technology is eliminating the jobs we once knew.

He also spoke of how capitalism is failing, due to abandonment of manufacturing sectors in pursuit of greater financial profits.

“This notion that capitalism delivers the goods… is BULL. And we sit there passively defending the free market. The free market doesn’t exist. It has NEVER existed.” — Bill DiFazio

Bill then spoke of how we have to make the land question, a question again, and how America needs to be the example of what’s possible — the good life.

Steven Pressman then spoke about a “Little BIG”, starting small by starting with children. He doesn’t believe it’s politically possible to start with a basic income that is given to everyone, but it is possible to start by providing a partial basic income to all kids. It costs less, and there’s no work disincentive, taking away the larger objections to BIG. Plus, we know the effects on kids make enormous impacts as adults and on poverty as a whole.

We already have a system of tax deductions for kids, but it mostly goes to the wealthier. It’s not widely known but those who make larger incomes get a larger deduction, and those who make little get less. It would make more sense to just turn this unequal deduction into an equal cash allowance. Meanwhile, paid parental leave is another policy that costs little and has huge effects.

Steven looked at child allowances all over the world and found that they have a fairly significant impact in raising the size of the middle class, an average of 6%, the same as the reduction in child poverty. So it’s a fairly simple improvement that we could do immediately at no extra cost, that would grow our middle class and reduce poverty, along with other long-term benefits.

“Instead of a tax exemption now, for a child, where if you don’t owe taxes you get nothing and if you’re in a low tax bracket you get very little, everybody gets the same dollar amount. So every child would get $1,000 or $2,000 or $3,000 and that would be paid for 100% by just eliminating tax exemptions for children.” — Steven Pressman

Peter Barnes then responded that it appears virtually a given that we will have a future where it is impossible for jobs to create a middle class and that we will need more than a little BIG as a result of such an inevitable future.

There are ways of raising revenue with negative incentives, that are good negative incentives, like taxing carbon for example. There are also work disincentives that we actually want, like for example being able to drop that third job instead of it proving fatal.

A comment was made during the Q&A about how the right won’t like a basic income regardless of how it’s presented, to which Steven replied that’s not the case at all, and has even been invited on Fox News before.

“One of the things I’ve learned over time, by talking about it in the way I have started to talk about it, focusing less on it in terms of reducing poverty, and talking more about it in terms of raising people up into the middle class, which really is the same thing, it makes a big difference.” — Steven Pressman

Session 12: “Unconditional Basic Income and the Contemporary Welfare System”: VIDEO | FULL NOTES

In this session, Diane Pagen gave a presentation that in my eyes represents the final damning nail in the coffin that should be our welfare system. (You can download the PowerPoint file [.pptx] and see for yourself.)

Essentially, block grants are being given to the states by the federal government to spend on their populations living in poverty, and the states, free to use the money as they please, aren’t using the bulk of the money on those in poverty. They are instead trying as hard as they can to not spend the money, so they can treat it as basically profit, for other expenditures instead.

Take Wyoming for example. Wyoming spent $32 million and did not spend the other $21 million in 2011 it had from the federal government to help its 64,154 citizens living under the federal poverty line. How many people received temporary assistance with the money they did spend?

674 of 64,154 under the FPL received TANF.

That’s right. 1% of those living in poverty in Wyoming got TANF. It also means Wyoming spent $48,643 on each of those 674 people to give each less than $5,000. Even worse, Wyoming is not spending an additional $31,509 per person that it actually has been given to allocate to those in need, and is instead spending that money elsewhere.

Looking at this another way, imagine if Wyoming said it would use its free federal money to give every single one of its citizens in poverty $842, which it could, and it instead gave them each a $100 dollar bill and pocketed the rest? That’s how block grants work. It allows states to rob the poor as middlemen in a transaction that would have no middlemen with UBI.

Sounds kind of familiar doesn’t it? We can’t just give people money, because they won’t spend it wisely? Other people know better how to spend that money? Wyoming spends 12% of its free federal money on 1% of the poor for whom it is intended, and it spends the rest elsewhere, not on meeting basic needs, but on job training, job searching, job readiness, job skills, work activities, resume writing… all in a country where at the time there were five times as many people looking for jobs than jobs available (it’s now 2:1). And Wyoming is not alone. It’s only one example.

So what’s another example of what states are spending their welfare money on, if not for welfare? In 2013, all 50 states combined spent over $1 BILLION on attempted prevention of out of wedlock pregnancies. Yep, the states are blowing money on behavior modification based on outdated views of religion-based morality, instead of on basic needs like food and housing. TANF really isn’t a program as much as it is purely a funding stream for states they can use however they please.

An actual welfare system does not exist in America. The welfare system as we know it, is actually just welfare for state governments and bureaucrats, and even corporations, not the American people.

“Large bureaucracy and infrastructure are being funded to deliver aid to tiny percentages of all Americans in need. Behavior modification has become the main purpose of [welfare], not income support. America is spending billions of dollars a year on a massive behavior modification program that is anti-child, anti-gay, and anti-woman.” — Diane Pagen

Steven Shafarman next began his presentation about the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and how it is effectively covert corporate welfare, introduced only after Nixon’s Family Assistance Plan (FAP) failed. FAP would have been a negative income tax form of basic income aimed at households instead of individuals, and almost became law when it passed the House and died in the Senate in 1970. According to Steven, Ford would have reintroduced FAP if he had beaten Carter in 1976.

It was this failure of FAP that resulted in the small tax credit tied to work we know as EITC, which currently does very little for childless individuals with a ceiling of $500 per year. This small credit tied to work then encourages companies like Walmart to provide assistance to workers to apply for it and other state and federal programs, so as to be able to pay workers even less.

Our present programs like EITC, TANF, and SNAP are not walks in the park to obtain. Most people who qualify for them don’t get them, and they allow and even encourage companies to use federal money to subsidize their wages, because workers have no power to say “No” to low wages like they would with an unconditional basic income. All jobs are not good jobs, and so tying income assistance to jobs unavoidably subsidizes jobs that aren’t good.

“The EITC does some good, but we must not be blinded to the fact it’s a hugely problematic program. The problem with TANF and the EITC and the conventional attitude in society, is that ALL jobs are GOOD jobs.” — Steven Shafarman

Additionally, nowhere in the Constitution does it say anything at all about jobs, and we should really focus on this point.

“I sometimes have this conversation with Conservatives and Libertarians who talk about strict construction of the Constitution, Well nowhere in the Constitution does it say anything about jobs. The word is not used. Nowhere in the Constitution does it say anything about corporations. The word is not used. The idea that Government is supposed to create jobs is an artifact of Franklin Roosevelt and the Great Depression, when Government became the ‘Employer of Last Resort’. So what I’m saying with Basic Income is that we need to focus on personal dignity, and that government’s job is to promote the ‘General Welfare’, not the ‘Special Welfare’ of individual citizens or of corporations.” — Steven Shafarman

During the Q&A, Diane asked an important question of the audience.

“Why does a state keeping millions of dollars they don’t need get looked at differently than people getting money they supposedly don’t need?” — Diane Pagen

We appear to be fine with people earning welfare as long as it’s millions or even billions of dollars instead of thousands of dollars, and as long as they’re rich and connected instead of poor and isolated.

Session 13: “Working with an Elegant Idea in a Messy and Chaotic World: Thoughts on Real-World Implementation of Basic Income”: FULL NOTES | DOWNLOAD (PDF)

Jim Mulvale began the final presentation of the day with a reminder to always keep in mind the four fundamentals of basic income:

- Universality — It must be guaranteed to all.

- Adequacy — It must be sufficient to cover basic needs.

- Unconditionality — It must free of any attached strings.

- Individual Autonomy — It must be paid to the individual.

With that reminder, UBI needs to be situated within a broader framework of equality-enhancing social programs that include both income support and protection measures. (The overall tax and transfer system and social services and supports.) Basic income alone cannot make everything possible, and we also need the support of those on the traditional Left as much as we need support from the traditional Right. So our message should not be elimination of government administration, but overall size and efficiency.

“We’re not going to completely eliminate bureaucracy, but we’re going to shrink it, and make it more efficient.” — Jim Mulvale

Supporters of basic income need to make contact with a variety of groups, and make commitments firmer and more solid. There needs to be a challenge to the old Left, to question their belief in a full employment economy and the desire to resurrect the old welfare state in the 21st century. Here in 2015, we need to be thinking about steady-state economics and redistribution, not old solutions born of old ways of thinking.

Jim also suggested we not keep things so simple as some others suggest, that we should instead embrace complexity and avoid a single justification argument, because there’s just so many reasons for a basic income. We need to adopt different strategies, depending on who we’re speaking to, and not stick to just one allegedly all-encompassing message.

We also need to take the long view on basic income, and avoid getting discouraged in the years to come.

There’s a long journey ahead and it won’t be easy.

During the Q&A there was a great response from a member of the Basic Income community on Reddit:

I want to highlight something about this presentation: Yes, we need to guard against the right wing model of BIG that would eliminate all other social services. But we also need to remember how horrible means-tested and conditional benefits are for the poor themselves, and the need to eliminate them as well. We should move toward a model where all government spending is either a social investment, such as infrastructure, or a basic income, in either cash or kind, such as universal education, healthcare, libraries, parks, childcare, etc., but welfare as we know it DESERVES to end.

After witnessing this Congress, I can’t agree more.

Welfare as we know it, truly does deserve to end.

It is a farce, a lie, a twisted illusion far removed from the reality of its workings and its toll on those it pretends to help among a country it divides. It is time to replace it with a system that universally helps everyone and treats citizens like adults instead of children.

There is a time to replace paternalism with trust, and that time is now.

Sunday, March 1, 2015

Session 14: “What can a Basic Income Guarantee Do For Us?”: FULL NOTES

The final day of the Congress began with Jude Thomas speaking about the great potential basic income holds for the arts [.pdf].

We now live in a world where much of the creation and distribution of art no longer has limits. For the first time in human history, a piece of music, a movie, a book, a poem, an image, these can all be duplicated an unlimited number of times at virtually no cost above the cost of original creation.

At the same time, modern patrons for the arts are media companies, academic institutions, and cultural institutions. Media companies are producing at this point almost nothing but sequels. Academic institutions only welcome a certain type of art with which they and their funders approve. And cultural institutions have a preference for old art and the idea old is somehow better. Combine these three primary patrons of art, and we get a system that is not nourishing innovation in the arts.

A basic income will open up the arts to everyone. With UBI, anyone can be an artist and anyone can be a patron. This will drive a level of innovation in the arts akin to a Second Renaissance. And in this world of digital abundance, where scarcity is gone and supply is infinite, it is extremely important to eliminate the costs of basic survival, because the digital distribution drives down what was once possible to earn from the creation of art.

Right now, the people who employ artists don’t really care if their art is innovative or original. With basic income we will be able to make our own decisions of what we like and dislike, and no longer have to put up with mediocre art like we do now without basic income.

Valerie Carter spoke next about the idea of a revenue neutral carbon tax (RNCT), its ability to provide a small basic income, and the importance to any basic income movement of recognizing the importance of union support.

(Note: the following large quotes are my own, not Valerie’s)

Unions never fought for the right to work. They fought for the right to income. If we can change this narrative, perhaps we can get unions supporting basic income.

Because workers are being booted out of the working class with the decline of unions, and unions are mostly loosely connected but have a strong sense of solidarity, it may be possible to position basic income as a key player in the transition between jobs and the effects tackling climate change will have on jobs in the eyes of union workers and union leadership.

“Many workers support the preservation or creation of virtually any jobs, whether or not they are environmentally destructive, because they need the income in the short term, and because in the U.S. there is no effective or functioning safety net when jobs are eliminated.” — Valerie Carter

For example, taxing carbon will hurt carbon economy jobs, which is what we all want, but if union workers are left out in the cold in the transition to a green economy, they will fight against that transition. Connect a carbon tax with a carbon dividend, and protect the financial security of all workers with a basic income guarantee, it then becomes possible to remove our barriers to using cleaner energy sources. Unions will get behind us instead of standing in front of us.

Workers are for environmentally destructive jobs because they need the income in the short term. They are focused literally on bread and butter issues.

Jim Mulvale then read Roy Morrison’s paper about the idea of a Basic Energy Entitlement (BEE) as a policy that could work hand in hand with a basic income, to bring about a fully sustainable global economy.

“The 21st century must choose between two paths. First, is the path toward building a prosperous, sustainable future of vital ecosystems. Second, is the continuation of a self-destructive business and pollution as usual, and an unfolding global 6th mass extinction.” — Roy Morrison

Because the Earth is capable of naturally handling 21 gigatons of carbon per year, an allotment per human could be set at 3 tons per person per year. With a world average of 4.5 tons per person, and a US average of 17.6 tons per person, most of the world and especially the US, would need to pay more for going over per capita limits. This money would then go to those using less than their limits, operating as a basic income for citizens of less developed nations.

Roy calculated the total additional average cost of a BEE per American as being about $185 per person per year. In his paper he also describes the potential for an ecological value-added tax (EVAT), where unsustainable goods can be made to cost more than sustainable goods, and the inherently regressive nature of this on the poor can be compensated for by universally sharing the revenue.

“The integration of a BEE with a BIG helps create a global dynamic of ecological justice. The BEE and the BIG are expressions of the global pursuit of sustainability and transition to a zero-waste zero-pollution economy characteristic of a sustainable ecological civilization.” — Roy Morrison

Session 15: “Let’s Face It: Basic Income is a Radical Necessity for Building Solidarity within our Precarious World”: FULL NOTES

Here Ann Withorn unleashed upon the crowd a torrent of quotes I can do no real justice in attempting to summarize, but I will endeavor to. She asked questions that needed to be asked, and gave answers that needed to be said.

“There is growing radical inequality, not only of income, but of wealth and power and respect. We who know we know that… what do we do about that?” — Ann Withorn

How do we confront a world of extreme and growing inequality? Those who support a basic income know how.

Ann spoke in the language of Guy Standing, speaking in terms of the idea of a new emerging class of precarious people leading precarious lives, known as “the precariat.” This new class is different. The old rules do not apply.

According to Ann, we can’t think about the precariat in the same way we could think about the working class. We’re in a precariat world with a precariat structure to it. This is radically different than the old world. We can’t assume the old ways of understanding things. There is a radical precariaty now. It’s not that full employment is a bad thing, it just doesn’t address the radical precariat. There used to be well paid shit work. Now kids can’t even be raised on shit work. There’s a belief that doing shit work will get us all somewhere. It won’t. Not anymore. Not in the age of the precariat.

One logical implication of all of this precariaty, is that we have to be afraid and there’s nothing we can do because it’s all so big. Ann declared this is not an accident. It’s not an evolution of capitalism. It’s been known even before we knew it, by those who didn’t want a social project at all.

This is what the fight for basic income will be about, this idea that we don’t need to be afraid, that we shouldn’t have to be afraid, because growing fear for survival in a world of growing abundance makes no sense at all.

Growing scarcity in a world of growing abundance makes no sense.

“If we say what we’re committed to, is the notion that people should be free, we can’t not have that. The idea of basic income is that everybody in the world who exists, deserves to exist with some security, and by doing that, and not just speaking about it, then we can achieve that before it’s too late. We have an obligation to go out of this room and figure out how to build a real movement for basic income.” — Ann Withorn

Ann also spoke of a student debt jubilee, and the need for it because “a bad job is a job you take just to pay off debt.”

She spoke of the need for real immigration policy and questioned why we care so much that people want to be here.

She spoke of the criminal justice system and how its very existence is its own crime.

“The criminal justice system is something we’re all responsible for. It’s a crime. We’re creating a murderous ‘justice’ system. And it’s racist… so deeply racist… If we’re willing to say everyone should have a basic income, why can’t we say there shouldn’t be any prisons? Why not? Why not?” — Ann Withorn

Ann was then followed by Diane Dujon, who was equally as inspiring to listen to as Ann. They are quite the one-two punch of a duo.

“Just because people are in poverty, doesn’t mean there’s something wrong with them. This is so delusional. People in this country delude themselves. People think they’re in the ‘middle class’, whatever that’s supposed to be.” — Diane Dujon

Diane sees basic income as leveling that field where people see value in those employed and no value in those not employed, and making people realize that everyone is deserving.

As Diane also stated, “At some point, we all need someone else’s help.” This isn’t just rhetoric. According to Jordan Weissman writing for the Atlantic, almost half of all Americans will live in poverty for at least a full year by the time we turn 60. Does it really make sense to think that’s a personal problem and not a structural problem? This isn’t just a tiny percentage. There’s a good chance that almost everyone you know has lived, is living, or will live, in poverty.

It’s when this happens, when we ourselves need help, that we more easily see it’s not our fault, that the system failed us. That the other half of the population does not also experience this, might be a large part of the reason our safety nets are designed so incredibly poorly, and why we insist on tying so many strings to all forms of assistance. We should instead be asking ourselves, what kind of help will I want, when I need it? And the answer to that is likely simply cash, because we are the ones who best know how to meet our own needs, not anyone else.

We live in too rich a country, for any citizen in its borders to be worried about obtaining one’s daily requirements to live and breathe. No one doesn’t matter, and we should treat each other in ways that reflect that.

“Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. We need to learn how to love one another. We need to learn how to be a society. We all matter.” — Diane Dujon

“I’m hoping that basic income allows people to find those inner things they were born with, that they can give to society without worrying where their next meal is coming from.” — Diane Dujon

Diane believes we need to value everybody, and we need them to know they are valued. I firmly agree and believe as she does, that unconditional basic income is the way we can make that happen. If we can together come to agree that everyone deserves the right to live unconditionally, that everyone should be guaranteed their basic needs of food and clothing and shelter, then we will all know our lives finally have inherent value to each other, because we have finally secured each other’s basic incomes.

Anything less than unconditional basic income falls short of a society that fully values all of its members.

During the Q & A, there was a memorable point made in response.

Just as we need to value each other, we need to recognize each other not as potential enemies, but as potential allies. The metaphor was made that we are all pancakes that can be flipped. But good luck flipping a pancake that hates you. It will come apart and instead make a huge mess.

This line of thinking is also why I support nonviolent communication. It can be difficult, and takes practice and fortitude, but just as nonviolent action is more effective than violent action, nonviolent communication (NVC) is more effective than violent communication. Judging others and not sticking to observations invites animosity and conflict where none need exist. If we watch the way we communicate, we can instead build bridges where none could otherwise exist. This is hugely important in the global discussion ahead of us, as we talk to each other about basic income, because it is itself such a radical shift in thinking.

Another great point made during the Q & A was that universality tends to be something liberals love and conservatives loathe, but not when it comes to stuff like “liberty and justice for all.” By leveraging the words of the Constitution in its promotion of the “general welfare”, those who may otherwise knee-jerk against basic income, can instead be caught off guard by Constitutional language, and by promotion of basic income as powerfully supporting ideals like freedom and liberty for all.

But are these ideals truly affordable?

“In general as far as how to pay for basic income, we take the programs that already exist that cost too much, and add to that the money that can be gained from reforming our tax system.” — Frances Fox Piven

This is a global decision with global consequences. If nation after nation establishes a basic income, every country without UBI will still have detrimental effects on all those with them, through the radicalizing effects of poverty and lack of social cohesion. As more and more nations have basic incomes, that’s when the world as a whole, may begin to operate differently.

“If everyone in a place like Iraq had a basic income, they’d probably have a sense of solidarity and democracy, and they could have peace there. I would like to suggest to you, to put all your efforts as well, to fight for basic income as a very important instrument of peace for the world.” — Eduardo Suplicy

And with that lofty suggestion made, we now reach the final session, with featured speaker, Peter Barnes, whose latest book With Liberty and Dividends for All makes the case for human commonwealth dividends.

Session 16: “Dividends for All: A Practical Solution to Economic and Planetary Insecurity”: FULL NOTES | DOWNLOAD (PDF)

“My basic proposition in this book is that capitalism has two fundamental flaws. It concentrates wealth and it destroys nature.” — Peter Barnes

These fundamental flaws of capitalism can be fixed with a single solution: dividends from common resources. These common resources are commonwealth. They are gifts of nature like water, societal creations like land value, and the value born from systems like the Internet.

There are certain advantages of commonwealth dividends over tax-funded government grants. They are: natural born rights vs. charity, shared inheritance revenue vs. taxation, external to any budgetary process, consisting of a great precedent set in Alaska, and fully bipartisan in appeal.

Even someone as conservative as Sarah Palin loves the Alaska Dividend, and even someone who hates taxes as much as Sarah Palin, has no qualm in levying taxes to fund a dividend, as she did in 2008 upon the oil companies to create the largest Alaskan Dividend in history.

Why?

Because the oil in Alaska is considered as belonging to the people of Alaska. So if a company wants to profit from their oil, they first need to pay a royalty to the people of Alaska as owners of that land and that oil within it. For this same reason, corporations should also pay a royalty to the citizens of nations to profit from their water, their minerals, their trees, their air, their sunlight, their electromagnetic spectrum, their Big Data.

Right now most corporations aside from those operating in Alaska and in Norway as premier examples, don’t pay these royalties. They aren’t charged these royalties. They instead get access to all of this for free. They get to pollute with nothing outside the occasional fine. And yet, one recent calculation finds that what is owed to us all instead, is approximately $10,000 per household in America.

Peter’s own calculation is around $3,000-$4,000 per man, woman, and child, just as in Alaska, fully universal, provided in entirely equal amount to every individual. Pair this universal dividend with the elimination of present benefit-in-kind welfare programs, and we’ve got a basic income of about $8,000-$10,000 created through no additional personal income taxes.

Considering that corporations are currently creating and finding all kinds of loopholes for paying taxes, as are the wealthiest citizens, this could be an extremely effective way of stopping corporations from continuing their free tax ride on the backs of everyone else. Norway makes oil companies pay a royalty of 50% in addition to a 28% corporate tax to gain access to their oil, and the companies still agree to those conditions because they still profit from them. It’s just that in the case of Norway, people profit from the oil too by way of free government services, and in the case of Alaska, people profit from the oil by way of free money and no state income taxes.

Is this the best way forward as something everyone on all sides can come to agree to? No increase in income taxes. No increase in consumption taxes. No new wealth taxes. Instead, it would just be a matter of charging a rent for access to that which we all own, and our sharing the value of that rent equally.

In addition we could use this as a means of fighting climate change. We could charge corporations for polluting, making it significantly more expensive to alter our climate, and whereas this action would otherwise be regressive for the poorest, paired with dividends it no longer remains so.

(Note: You can take action on this right now. Contact your local representative in Congress to support the Healthy Climate and Family Security Act of 2015.)

Peter also described what he sees as an older versus younger generation divide, where the old are represented by traditional Democrats and Republicans, and the new are represented by progressives and libertarians within these parties. And it is this newer generation who better recognizes technology and the years ahead we have to look forward to, of decreasing jobs and increasing inequality. Working together as populists against the older plutocrats, the potential is there to shift the power structure towards a basic income in the form of Alaskan-style commonwealth dividends.

Is this something we can all agree upon?

Is this the shortest path to UBI in the USA?

The Alaska Model seems to shine a light on the way forward. Will we take it?

It seems that perhaps some are already looking into the possibility…

Closing Discussion: “Are we ready to start a political movement for a Basic Income Guarantee in the United States?: VIDEO | FULL NOTES

This was the final gathering of the weekend, and occurred at The Commons Brooklyn on Sunday night. I was too heavily involved in this meeting to take full notes as I did in all the other sessions, but there are still notes to share courtesy of Karl Widerquist.

Karl opened up the meeting with a quick introduction of the founding of USBIG back in 1999, and how 15 years later, it appears that it’s finally time to organize a full-on political activist movement intent on the establishment of basic income in the United States. This meeting was organized for that purpose, to take the first steps in that direction.

Plans have also already been made to next organize a 501c(3) and 501c(4) for the purpose of funding and political advocacy. The names of these organizations soon to be formed, have yet to be determined. With that said, we all introduced ourselves and then broke off into variously focused discussion groups.

A strategies and tactics group coalesced to talk about the Swiss initiative and how it successfully got and continues to get a great deal of attention in the press and from everyone else. So what can be done in the US to get attention to the issue of basic income too?

One suggestion was made to focus on getting a million signatures in support of basic income to deliver to the incoming new President when he or she takes office in 2017. Another suggestion was to get a state initiative passed somewhere to become the second state with some form of universal dividend like Alaska.

Any strategy should involve asking people how basic income will affect them, as a way of getting people thinking about it personally.

Another group coalesced around the focus of basic income and women. How will UBI affect women? How can women best be engaged to support the idea?

A suggestion was made to share what the rape crisis shelter in Vancouver is doing, in its messaging of how not having basic income is a big part of the reason women end up there. Here’s a video of someone from the shelter talking about basic income at last year’s BIEN Congress in Canada.

Another group got to talking about possibly organizing a team to focus on updating Wikipedia to have more links about basic income where relevant, and more accurate well-sourced entries. There is also already a group with this purpose on Facebook.

Finally, the group I was a part of discussed what is being done in Germany by Mein Grundeinkommen (My Basic Income) to create the revenue through multiple means to grant basic incomes to individuals as a kind of raffle. Michael Bohmeyer explained how they’ve already rewarded people with basic incomes (which you can read more about here), how they are expanding it, and how they continue to intend to expand it.

What they are doing now is a blend of the cards we use in grocery stores, and credit cards that offer cash back. By copying one card thousands of times, the people who use this cloned card quickly accrue 1% of their shared total expenditures, which is then given to someone as a basic income. The message here is “You are the 1%”, flipping the script on our growing inequality. This is a brilliant example of directly hacking the system to immediately give some people basic incomes right now, and show what’s possible when more people have basic incomes.

Johannes Ponader, also part of Mein Grundeinkommen, explained what is to come next, which is to essentially hack a land value tax-based UBI. Land will be bought, and the rent from that land will create a commons by those using a new local currency. As people begin to adopt this currency and more property is purchased to back it, a larger and larger commonwealth will be created, which can either be rewarded to some people in the form of basic incomes, or returned to everyone as partial basic incomes. This is my understanding at least.

I think these are brilliant strategies. Michael and Johannes are doing great work in Germany to immediately get more people liberated by basic incomes. They would love to one day fill a room with people who have basic incomes, and just see what happens. What kind of ideas would come out of such a room? What happens when fully emancipated, entirely free people get together? It’s a good question.

What would happen?

What would you do with a basic income?

This is the question it all comes down to doesn’t it? And once you start asking yourself this question, you might begin to ask yourself another question…

What will you do to guarantee that you, your family, your friends, your coworkers, and everyone else has a basic income tomorrow?

What will you do to make basic income happen?

This is the question I now ask myself everyday. If you’ve read this entire summary from top to bottom, perhaps you too are asking it, or will ask it soon. It’s hard to encounter such information as witnessed and reported here and not at least begin to ask such a question.

The idea of basic income is too important to not make happen. Recently described by Fast Company as “a bipartisan solution and world changing idea”, it truly is an idea whose time has come, and an idea that has for far too long been perceived as an impossibility in a world of perceived scarcity.

But that scarcity no longer exists as it once did. We need only look around us at all the digital abundance, the technologically-enhanced productivity, and the record-shattering amounts of inequality. 1% of the world will soon own more than the other 99%. This level of inequality has consequences.

Scarcity is not our problem. Distribution is our problem.

Politicians and corporations are not our problem. Our lack of democracy is.

Handouts and entitlements are not our problems. Our lack of economic rights are.

Decreases in wages and decreases in hours are not our problems. Our lack of power to say “No” to employers is.

Technology is not our problem. Our refusal to make it work for all of us is.

The year is 2015. The idea of basic income is now finally spreading like wildfire, and it needs to spread like wildfire, because sometimes in order to put out a fire, you have to light one.

What will you do to help light this fire? What will you do to spark it within the hearts and minds of others?

This is our world. Let’s make it work with basic income.

Let’s stop fighting over going right or left. Let’s instead go forward.

I just want to take a moment here at the end of this report to thank all of my patrons again for making my trip to New York possible to record all of this, and additionally thank everyone there for being a part of the NABIG Congress itself and for all the great discussions and new friendships, and all of the organizers at USBIG and BICN for making it all happen. Thank you. Thank you all so much.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.